Starts With A Bang podcast

https://anchor.fm/s/afe6391c/podcast/rssEpisode List

Starts With A Bang #127 - Satellites and space pollution

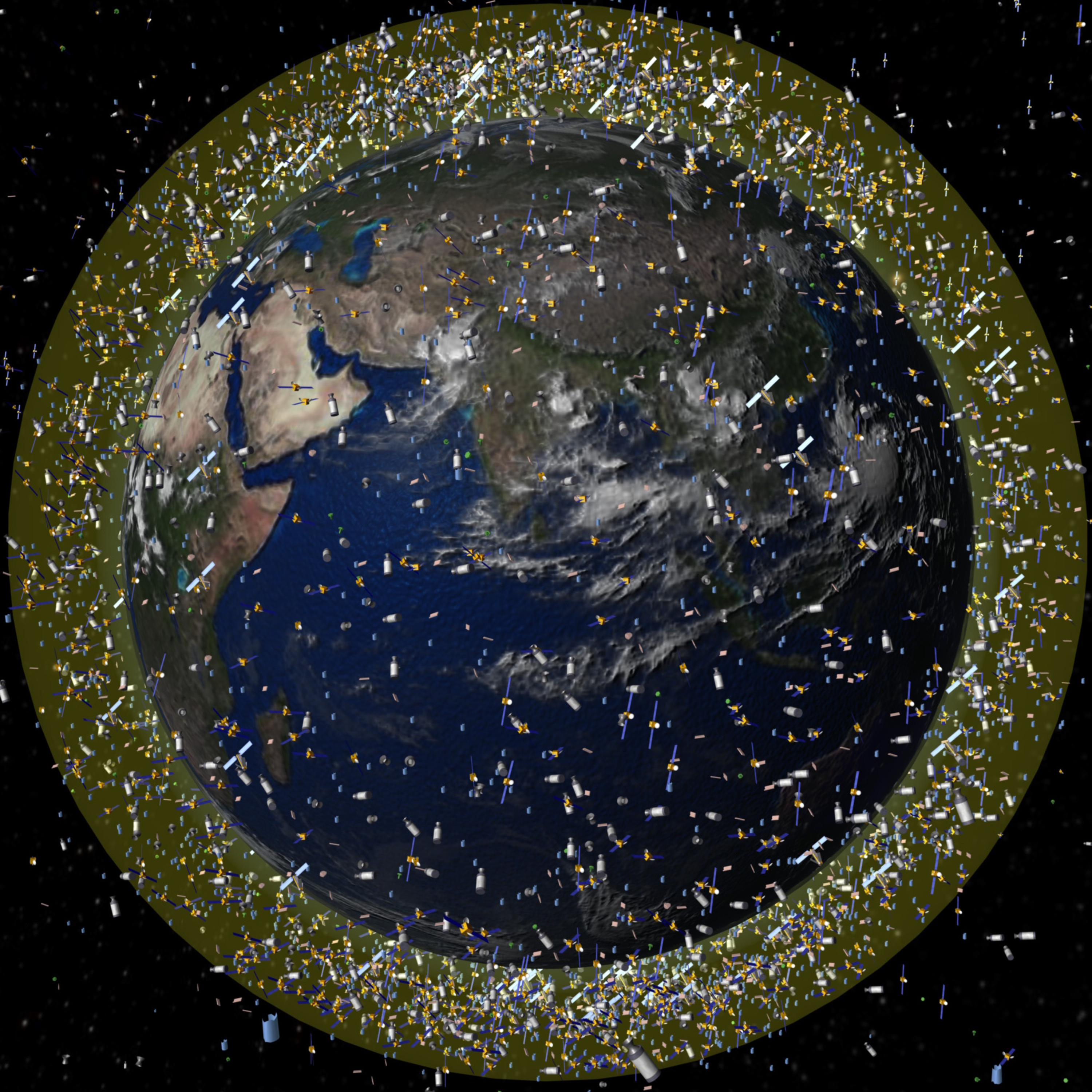

When most of us were children, and we went to a rural area with clear skies overhead at night, we were all greeted by the same familiar sight: a dark night sky, glittering with many hundreds or even thousands of stars. Depending on how dark your sky was, you could spot up to 6000 stars at once, as well as deep-sky objects, the plane of the Milky Way, and only the rare, occasional satellite streak. As time went on, more and more satellites were launched, bringing us up to around 2000 active satellites as of 2019.And then we entered the era of satellite megaconstellations, beginning with the launch of the first Starlink satellites. Now, nearly 7 full years later, there are over 17,000 active and defunct satellite payloads in orbit, with approximately 100 times as many satellites proposed in the coming years. From satellite communications to direct-to-phone links to the proposition of AI data centers in space, the number of proposed use cases has exploded. However, as the environment around Earth becomes more crowded, the risks, the harms, and the potential for disaster all grow evermore severe, with woefully insufficient (or, sometimes, no) mitigation measures in place.Is this a cause for despair? Or could this be our finest hour in terms of combatting these new forms of pollution. I've brought expert Dr. Meredith Rawls onto the podcast this episode to discuss satellites and space pollution, and the conversation ranges from thoughtful to passionate to pessimistic to hopeful many times over. Have a listen; you don't want to be underinformed about this one!Helpful links:IAU's center for the protection of dark and quiet skies: https://cps.iau.org/NRAO/VLA's paper on radio telescope operations coordinating with satellite providers: https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.15068v1Vera C. Rubin's public alerts stream: https://rubinobservatory.org/news/first-alertsAn article on Rocket plumes: https://www.nature.com/articles/s43247-025-03154-8Meredith's Nature News and Views piece regarding streaks in space telescopes: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-03725-x The latest on the CRASH clock: https://outerspaceinstitute.ca/crashclock/Astronomers argue for astronomy on the ground and in space: https://spacenews.com/the-future-of-astronomy-is-both-on-earth-and-in-space/ and Yvette Cendes's previous appearance on the SWAB podcast: https://soundcloud.com/ethan-siegel-172073460/starts-with-a-bang-77-stellar-destruction and https://open.spotify.com/episode/4xnBB0Ma4SzHk8ulziOidk(The illustration shows all tracked objects in space as of 2025, as shown by the European Space Agency. The size of the objects, including intact satellites as well as space debris, is greatly exaggerated, but the number of objects shown is actually far less than the number of objects in space now in 2026, just one year later. Credit: European Space Agency)

Starts With A Bang #126 - The origin of dust

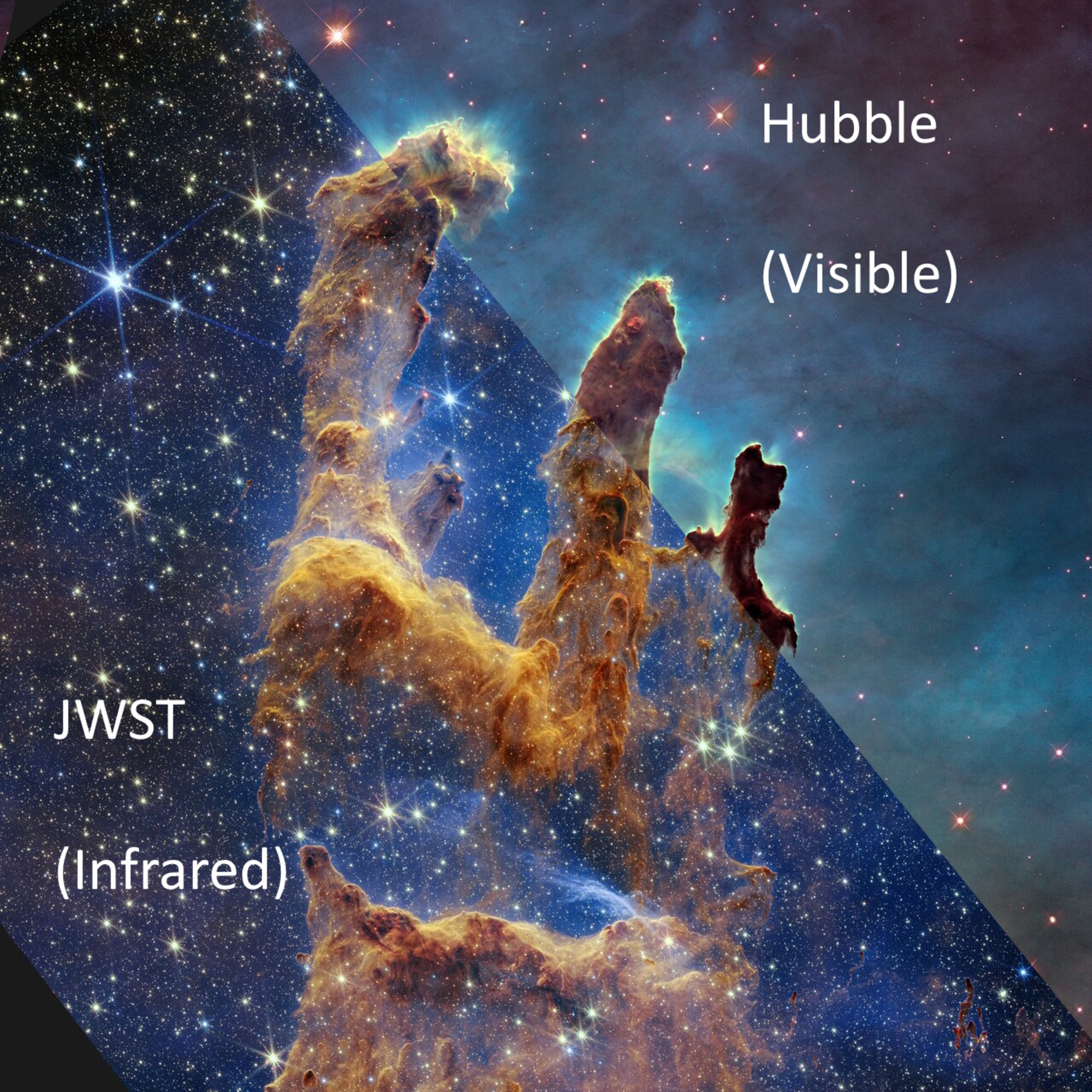

Out there in the Universe, we're most aware of what we see: of all the forms of light that arrive in our eyes, instruments, telescopes, and detectors. Much more difficult to see, as well as understand and make sense of, is the wide array of "stuff" that's present, but that isn't readily apparent to the apparatuses we normally use to reveal the Universe. From the dark bands of the Milky Way to the light-blocking materials in nebulae and clouds, all the way to lining the arms of spiral galaxies and the heavy, long-chained molecules found in protoplanetary disks, cosmic dust is perhaps our most enduring mystery.Sure, it gives absorption signatures that we can leverage, and at long enough infrared wavelengths, dust that gets heated has its own emission signatures, but we can generally only observe it in detail up close: within our own galaxy or in the nearest galaxies of all. That poses a huge challenge, because the origin of dust, including from a cosmic perspective, remains only very poorly understood. We may have identified many dust-producing sources in the Universe, and we may understand that the young Universe was a lot less dusty than our modern cosmos, but we still lack an understanding of how this has come to be the case. Thankfully, we have scientists on the case, like this month's guest: Dr. Elizabeth Tarantino of the Space Telescope Science Institute.In this fascinating interview, she takes us on a journey spanning gently dying stars, the formation of new stellar systems, the outskirts of our cosmic backyard, and to the farthest reaches of JWST as we try and piece this mysterious cosmic story together. Buckle up for an exciting and informative ride; you'll be glad you tuned in!(This image shows the Pillars of Creation within the Eagle Nebula, as assembled by two entirely different data sets. On the upper-right, a visible light view showcases how this dusty region obscures the stars behind it. On the lower-left, an infrared view showcases the stars, although reddened, that can be seen behind the dusty cloud. At still longer wavelengths, the dust would glow due to the heat inside of this region. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, J. DePasquale, A. Koekemoer, A. Pagan (STScI), ESA/Hubble and the Hubble Heritage Team)

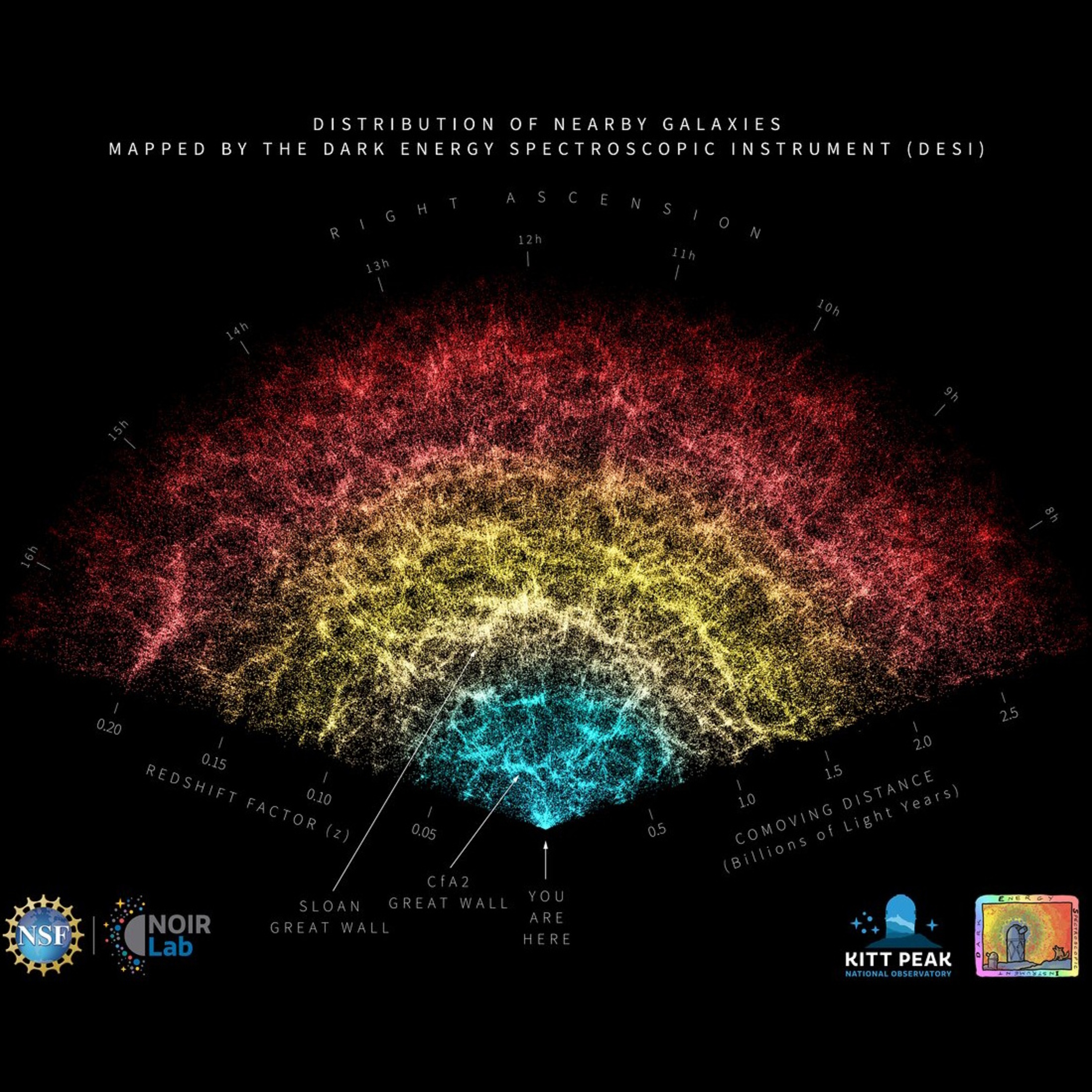

Starts With A Bang #125 - Large-scale structure

One of the most exciting developments in modern astrophysics isn't merely our standard "concordance cosmology" model, but rather the cracks that seem to be emerging in it. Sure, we've said for some 25 years now that our Universe is 13.8 billion years old, is made of mostly dark energy with a substantial amount of dark matter, and only 5% of all the normal stuff combined: stars, planets, black holes, plasmas, photons, and neutrinos. But more recently, a couple of cosmic conundrums have emerged, leading us to question whether this model is the best picture of reality that we can come up with.We don't merely have the Hubble tension to reckon with, or the fact that different methods yield different values for the expansion rate of the Universe today, but a puzzle over whether dark energy is truly a constant in our Universe, as most physicists have assumed since its discovery back in 1998. While "early relic" methods using CMB or baryon acoustic oscillation data favor a lower value of around 67 km/s/Mpc, "distance ladder" methods instead prefer a higher, incompatible value of around 73 km/s/Mpc. Now, on top of that, new large-scale structure data seems to throw another wrench into the works: supporting a picture of evolving dark energy, and specifically one where it weakens over cosmic time.Here to guide us through this is Dr. Kate Storey-Fisher, a cosmologist whose expertise is exactly on this topic, and who herself has recently become a member of the very collaboration, DESI, that provides the strongest evidence to date for evolving dark energy. The story, however, is only just beginning, and with current and future observatories poised to collect superior data, we take a look ahead as to what's in store for the Universe, and for those of us who are working oh so hard to try and understand it.(This image shows a "slice" through 3D space of the galaxies mapped out by the DESI survey, and color-coded by their distance/redshift from us. Features such as "great walls" can be seen even by eye within the data. Only 600,000 galaxies, or about 0.1% of DESI's total data, is displayed in this figure. Credit: DESI Collaboration/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/R. Proctor)

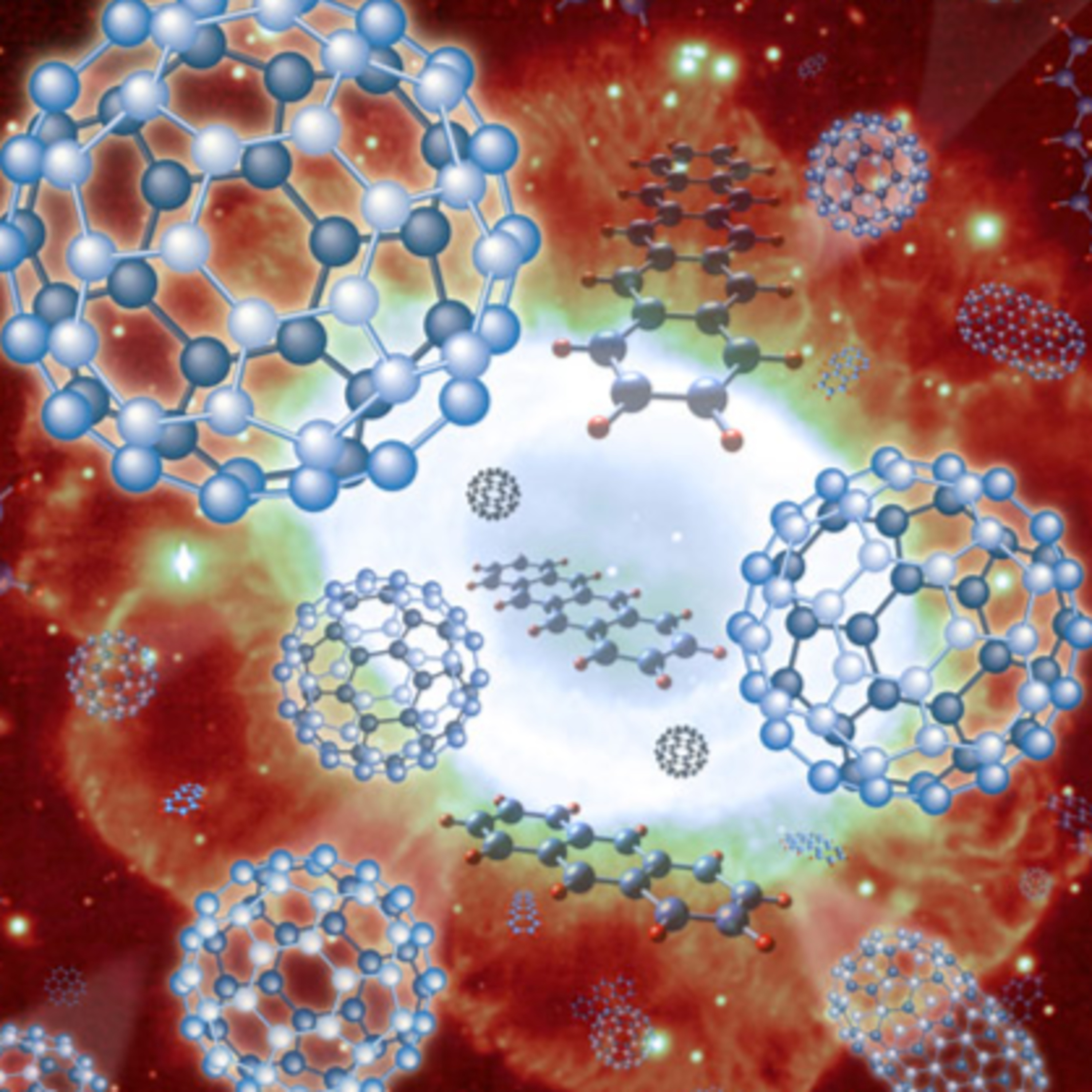

Starts With A Bang #124 - Astrochemistry

All across the Universe, stars are dying through a variety of means. They can directly collapse to a black hole, they can become core-collapse supernovae, they can be torn apart by tidal cataclysms, they can be subsumed by other, larger stars, or they can die gently, as our Sun will, by blowing off their outer layers in a planetary nebula while their cores contract down to form a degenerate white dwarf. All of the forms of stellar death help enrich the Universe, adding new atoms, isotopes, and even molecules to the interstellar medium: ingredients that will participate in subsequent generations of star-formation.For a long time, however, we'd made assumptions about where certain species of particles will and won't form, and what types of environments they could and couldn't exist in. Those assumptions were way ahead of where the observations were, however, and as our telescopic and technological capabilities catch up, sometimes what we find surprises us. Sometimes, we find elements in places that we didn't anticipate, leading us to question our theoretical models for how those elements can be made. Other times, we find molecules in environments that we think shouldn't be able to support them, causing us to go back to the drawing board to account for their existence.Where our expectations and observations don't match is one of the most exciting places of all, and that's where astrochemist and PhD candidate Kate Gold takes us on this exciting episode of the Starts With A Bang podcast! Have a listen, and I hope you enjoy it as much as I enjoyed having this one-of-a-kind conversation!(This image shows the fullerene molecules C60 and C70 as detected in the young planetary nebula M1-11. This 2013 discovery was the first such detection of this molecule in this class of environment. Credit: NAOJ)

Starts With A Bang #123 - Alien physics

One of the great discoveries to be made out there in the grand scheme of things is alien life: the first detection of life that originated, survives, and continues to live beyond our own home planet of Earth. An even grander goal that many of us have, including scientists and laypersons alike, is to find not just life, but an example of intelligent extraterrestrials: aliens that are capable of interstellar communication, interstellar travel, or even of meeting us, physically, on our own planet. It's a fascinating dream that has been with humanity since we first began contemplating the stars and planets beyond our own world.Most of us, including me, personally, have assumed that this latter type of alien would not only be more technologically advanced than we are, but would also be far more scientifically advanced as well. That not only would they understand everything we presently do about the fundamental laws of physics, but far more: that they'd be a potential source of new knowledge for us, having equaled or exceeded everything we'd already gleaned from our investigative endeavors. And that assumption, as compelling as it might be, could be completely in error, argues physicist and author Dr. Daniel Whiteson.That's why I'm so pleased to bring you this latest episode of the Starts With A Bang podcast, where Daniel and I meet to discuss this very topic, with me taking the side of my own human-centered assumptions and Daniel taking a far more broad, philosophical, and cosmic approach: the same approach he takes in his new book, Do Aliens Speak Physics? And Other Questions About Science and the Nature of Reality. Have a listen to this fascinating conversation, see which set of arguments you find more compelling, and check out his book. You won't be disappointed!(This image shows the cover of Dr. Daniel Whiteson's and Andy Warner's newest book, Do Aliens Speak Physics? And Other Questions About Science and the Nature of Reality, which debuted on November 4, 2025! Credit: W.W. Norton & Company)

Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast