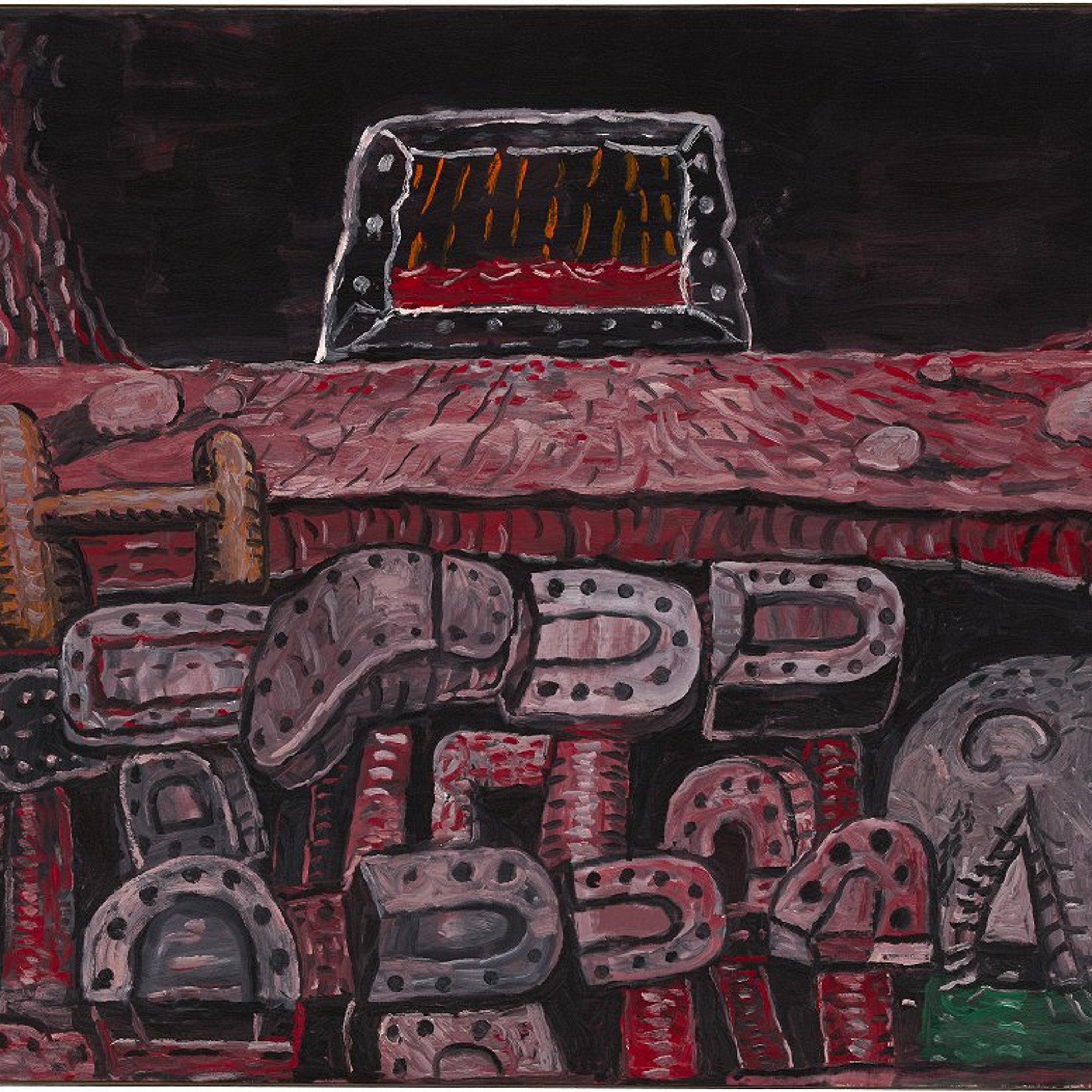

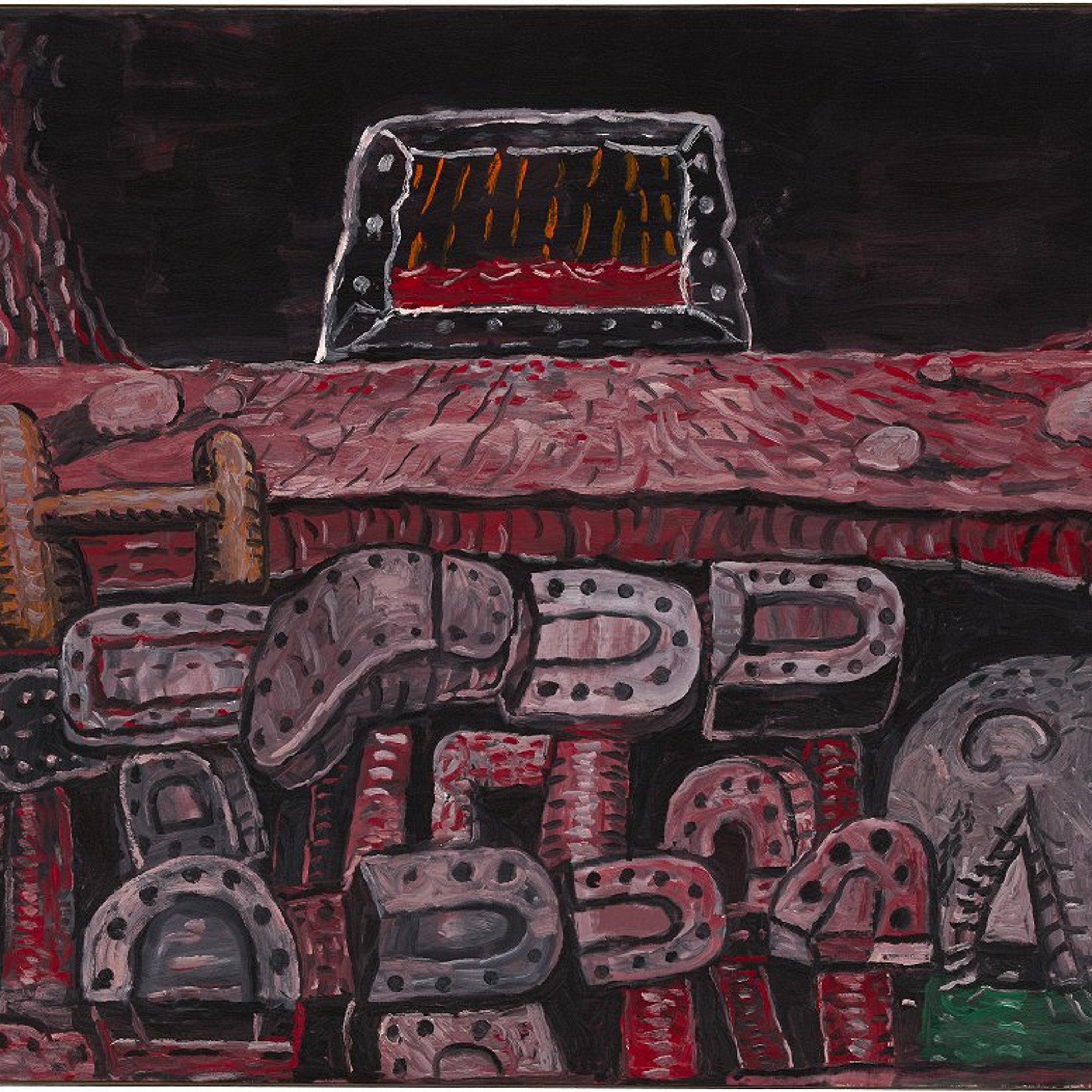

Philip Guston’s inner conflicts and the turmoil he observed in the world are brought together in this painting, titled Pit. A dark, hellish scene is characteristically defined with creamy applications of oil paint and bold outlines. The top section of the work is dominated by a painting within the painting that depicts orange rain streaming into red water, while its frame emits a white ‘light’ that appears to part an elemental sea of red flames. The tip of a wooden ladder bridges the sharp...

Philip Guston’s inner conflicts and the turmoil he observed in the world are brought together in this painting, titled Pit. A dark, hellish scene is characteristically defined with creamy applications of oil paint and bold outlines. The top section of the work is dominated by a painting within the painting that depicts orange rain streaming into red water, while its frame emits a white ‘light’ that appears to part an elemental sea of red flames. The tip of a wooden ladder bridges the sharp divide between a barren expanse and a gaping abyss. The pit opens up to expose a tangled web of dismembered legs, acting as a powerful metaphor for society.

At the right-hand end of the pit is an oversized, disembodied eye, which stares down into an isolated patch of green. The art critic Dore Ashton described this reoccurring motif as a ‘naked eye’, which she saw as representative of the artist himself.

A leading Abstract Expressionist since the early 1950s, Guston’s late figurative works initially came as a shock to his peers and to art critics alike, but are now considered his most significant contribution to twentieth-century American art. In the 1960s and 70s Guston became deeply disturbed by the Vietnam War and his departure from abstraction reflected a growing desire to engage with the wider community.

Guston described ‘feeling split, schizophrenic.’ He questioned ‘what kind of man he was sitting at home, reading magazines’ about the Vietnam War and ‘the brutality of the world’, and then retreating to his studio ‘to adjust a red to a blue.’ As an artist, Guston decided that there must be something more he could do for society.

Guston’s paintings of this period show an artist with his eyes wide open to the world around him. Indeed, Guston now deemed the visible world to be ‘abstract and mysterious enough’ that he did not need to ‘depart from it in order to make art’.

View more

Comments (3)

More Episodes

All Episodes>>Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free