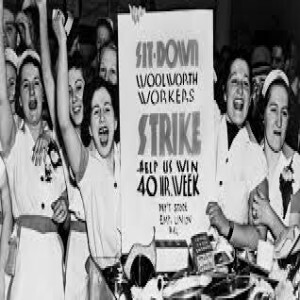

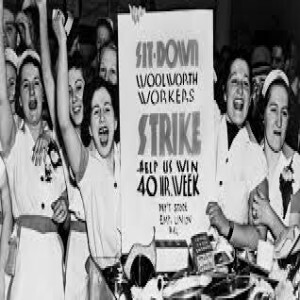

On this day in labor history, the year was 1937.

That was the day whistles blowing and the call to strike could be heard through the aisles of Woolworth in downtown Detroit.

108 saleswomen walked away from their workstations and cash registers.

The eight-day sit-down had begun.

The young women saw from the experience in Flint that sit-down strikes could win.

They evicted management, barricaded the doors and found 200 or so customers still inside the store, wanting to join them.

The strikers issued their demands: a 10 cent an hour raise, an eight-hour day, union recognition and a union hiring hall, free uniforms and laundering and more.

Kresge department stores immediately gave their workers a raise in order to prevent similar stoppages.

The striking women at Woolworth made themselves comfortable and the sit-down soon spread to a second store.

Leaders from Local 705 of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees threatened a national strike if demands were not met.

Union cooks provided meals and union musicians provided entertainment. Hotel workers from across the city picketed in front of the store to show solidarity.

After seven days, Woolworth’s management caved and agreed to most of the strikers demands.

High turnover in the workforce would undo contract gains at area Woolworth stores soon after the sit-down.

But the victory electrified retail workers across the country.

The sit-down spread to retailers in St. Louis, New York, San Francisco, Minnesota and Washington.

In Three Strikes: Miners, Musicians, Salesgirls, and the Fighting Spirit of Labor’s Last Century, Dana Frank notes that, “over 60 years later, unions today in department stores all over the country owe their existence in part to the Woolworth strike.”

More Episodes

All Episodes>>You may also like

Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast