September 9, 2016

On this day in Labor History the year was 1919.

That was the day that the Boston police went out on strike.

The police in Boston had not had a raise for over six years.

They worked long shifts, sometimes even more than 80 hours a week.

The police force was predominantly Irish.

Many had served as US soldiers in World War I.

Fed up with their working conditions the police formed a union and joined the American Federation of Labor.

Boston’s Police Commissioner Edwin U. Curtis refused to recognize the police union and fired nineteen police officers for their organizing efforts.

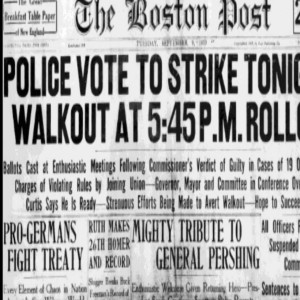

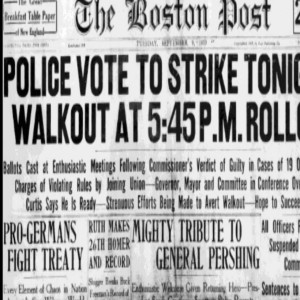

In response the new union voted overwhelmingly in support of a walkout.

More than 1,100 police officers voted to strike with only 2 voting no.

Across the country newspapers made dire predictions about the collapse of law and order.

While there was an upsurge in crime due to the lack of police on the streets, the press wildly exaggerated what was happening in Boston.

Newspapers ran stories about gangs running wild with rioters and communists attacking women, fueling Red Scare fears.

The entire labor movement came under attack.

Massachusetts Governor Calvin Coolidge declared, “There is no right to strike against public safety by anyone, anywhere, anytime.”

His hardline stand against the striking police helped propel him to the national stage and eventually to the oval office.

The striking policemen were fired and replaced with unemployed WWI veterans.

In response to the national outcry over the strike, the AFL revoked the charters for other police unions.

The Boston police strike is subject of the page-turner The Given Day by author Dennis Lehane.

A fictionalized account of the events surrounding the strike, the novel follows the experiences of one Irish policeman during this tumultuous time.

More Episodes

All Episodes>>You may also like

Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast