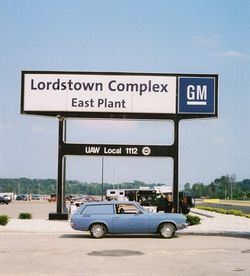

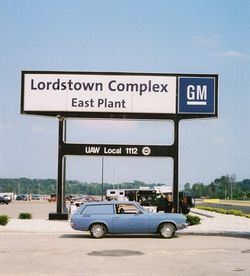

On this day in labor history, the year was 1972.

That was the day autoworkers at GM’s Chevy Vega plant in Lordstown, Ohio walked out on strike.

The strike lasted for 18 days.

The issues that fueled it were reminiscent of the sit-downs and wildcats that built the UAW in the 30s and 40s.

Workers at Lordstown wanted greater control over the production process.

The young, integrated workforce of the 1960s social protest era was fed-up with long days, forced overtime, increased automation and dangerous speedup on the assembly line.

Long-standing grievances numbered in the thousands and disciplinary firings were common. Absenteeism was rampant.

Morale was so low that cars left the assembly line incomplete or vandalized.

By the time the strike ended, many felt it was called to simply allow workers to blow off steam.

There was no real change to the production process.

But jobs eliminated in the 1970 contract were restored and some 1400 disciplinary layoffs were dropped.

The worker malaise suffered there came to be known as the “Lordstown Syndrome.”

In his book Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class, Jefferson Cowie notes that the strike compelled the Senate to hold hearings on alienation at work.

Its’ committee produced the report Work in America.

This report confirmed, “many workers at all occupational levels feel locked in, their mobility blocked, the opportunity to grow lacking in their jobs, challenge missing from their tasks.”

Cowie concludes that the strike and report “initiated the quality of work life movement that sought to redesign work, introduce automation differently and invest in ‘human relations’ strategies, most of which continued to empower management, not workers—albeit with a gentler hand.”

More Episodes

All Episodes>>You may also like

Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast