HEATED (private feed for chris_xr@posteo.de)

https://api.substack.com/feed/podcast/2473/private/e8bc7fe2-974a-46e3-b2bb-4f0b3495b69d.rssEpisode List

Listen to our interview with Rep. Ro Khanna

It is very difficult to get television news networks to tell climate change stories—especially ones that place the blame on fossil fuels. The House Oversight Committee’s ongoing investigation into Big Oil, and its role in misleading the American public about climate change, is an example.According to Rep. Ro Khanna (D-CA), who is leading the investigation with committee Chairwoman Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney (D-NY), it’s been tough to get television news to cover this—but not because it’s not an important story. “I've been told by bookers who have me on their television shows that climate is hard to get ratings for,” he told HEATED in an extensive interview about the investigation. “They say climate is a tough thing to cover on television.”So Khanna is vying for attention from other sources. In a 30-minute interview, we discuss the investigation’s challenges—from media coverage, to the fierce backlash from Republicans and the oil industry, as well as resistance from some Democratic colleagues. We also talk about the successes of the last year, where the investigation goes from here, and what interested citizens can do to help. This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit heated.world/subscribe

How banks finance the climate crisis

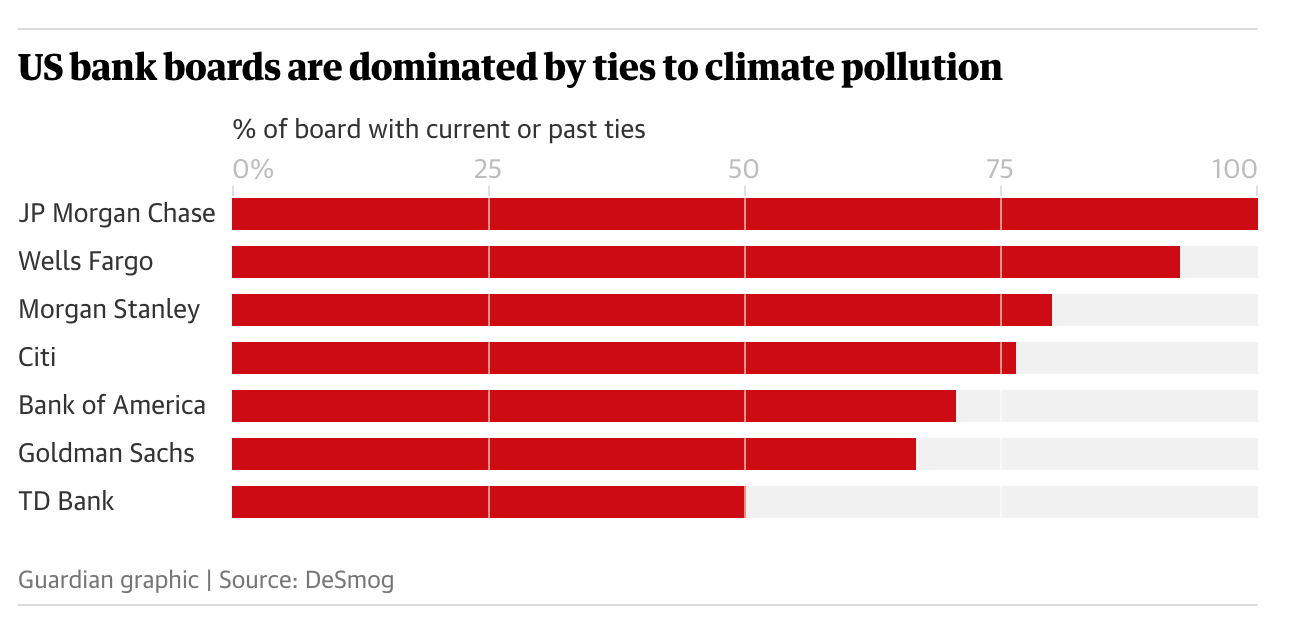

Today’s newsletter is a collaboration with Emily Holden at Floodlight, a new non-profit news organization dedicated to investigating the corporate and ideological interests holding back climate action. ICYMI, we ran an interview with Holden about Floodlight’s launch last month.Our article today investigates how decision-makers at major banks have conflicts of interest on climate, and what that means for the projects they back—like Line 3 in Northern Minnesota. It is also running in The Guardian.At the top of today’s e-mail, you’ll also find a behind-the-scenes, podcast-style audio interview about this story. It starts with a discussion between Emily and I, and then ends with an interview with Giniw Collective founder Tara Houska, who’s been leading direct actions against the Line 3 pipeline.I hope you enjoy this collaboration! Let me know what you think in the comments, and please consider supporting this 100 percent reader-funded, independent journalism with a subscription if you can.By Emily Holden for Floodlight and Emily Atkin for HeatedU.S. banks are pledging to help fight the climate crisis alongside the Biden administration, but their boards are dominated by people with climate-related conflicts of interest, and they continue to invest deeply in fossil fuel projects.Three out of every four board members at seven major US banks (77%) have current or past ties to 'climate-conflicted' companies or organizations—from oil and gas corporations to trade groups that lobby against reducing climate pollution, according to a first-of-its-kind review by climate influence analysts for the blog DeSmog. One of the controversial projects those board members have chosen to back is the new Line 3 tar sands oil pipeline, currently under construction in northern Minnesota. If completed, the project would allow Canadian oil giant Enbridge to double the amount of high-polluting tar sands oil it currently transports through the region to 760,000 barrels per day.Environmental groups estimate the new Line 3 would add 50 new coal plants’ worth of carbon emissions to the atmosphere every year for the next three to five decades. They say it is incompatible with the Biden administration’s climate and environmental goals, and they argue the project never should have been approved. They add that the Trump administration didn’t independently review the risks of building a tar sands pipeline underneath the headwaters of the Mississippi River, which flows all the way to the US Gulf Coast.Neither Biden nor the banks funding Line 3 have acknowledged these concerns, and time is running out to halt construction. So in recent weeks, Indigenous water protectors in Minnesota have resorted to physically chaining themselves to Enbridge equipment, while activists across the country have been chaining themselves to the doors of the banks who finance the pipeline.“There’s been a lot of complacency. People have been pursuing comfortable routes of advocacy,” said Tara Houska, whose group Giniw Collective has led several direct actions against Line 3. “I don’t think we’re going to get the answers we need comfortably.”The financing behind Line 3Enbridge has seven active loans relevant to Line 3, totaling $11.5bn, according to the Rainforest Action Network. In addition, banks have underwritten bonds to Enbridge totaling $5bn since the autumn of 2019, the group said.From the U.S., Bank of America, Citigroup, JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo have made the project possible with billions of dollars in loans, although it’s impossible to tally precisely how much they have financed for the pipeline specifically. Another five large Canadian banks are also financing Enbridge, according to Ran.Out of these nine North American banks backing Enbridge, six have recently published net-zero climate goals, pledging to align their investments with the international Paris climate agreement.“The banks are gorging on doughnuts and then eating an apple afterwards,” said Richard Brooks, the Toronto-based climate finance director for Stand.earth. “We certainly can’t rely on banks or the private sector to lead us into climate safety and lead us toward emissions reductions. We need policy, we need regulation. We need government to act.”DeSmog found Canadian banks have the highest percentage of directors with climate-conflicted ties: 82%. That figure was significant in the UK and elsewhere in Europe as well, at 78% and 61%, respectively.The struggle to get banks to defund Line 3In February, the group Stop the Money Pipeline began a campaign to demand that banks withdraw their financial support of Line 3.But despite numerous direct actions across the country, the effort has not been nearly as successful as previous climate campaigns targeted at banks, like the campaign to end funding for drilling in the Arctic national wildlife refuge.The progressive Minnesota congresswoman Ilhan Omar pointed to previous environmental victories and said activists must keep fighting. “We were able to stop the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline because activists collectively organized in large numbers to oppose it—we must use that same energy to stop this pipeline from causing irreversible damage,” she said.Juli Kellner, an Enbridge spokesperson, argued Line 3 was a safety-driven project because it was replacing an older pipeline. She said it had received all its permits after a thorough review process.“Shutting down existing pipelines does not erase demand. It merely forces the transport of essential energy by less efficient means such as ship, truck, and most notably rail,” Kellner said. “It is Enbridge’s responsibility to transport the energy people rely on daily by pipelines - the safest, most efficient means of transporting energy. It is also our responsibility to do what we can to address climate change. That is why we’ve set a target of net-zero emissions by 2050 and laid a credible path to achieving it, including tying compensation of our executives to our performance in this area.”The most climate-conflicted banks: JPMorgan, Wells FargoMuch of the U.S. economy is built on fossil fuels, and people with enough experience to be appointed to bank boards are likely to have some connection to climate-conflicted organizations. But the DeSmog analysts said the heavy representation of industry on boards shows a “lack of creativity” in recruitment and is probably why bank policies aren’t more environmentally progressive.“Some of these banks have pledges, but it’s about ensuring that they see them through. We’re simply asking the question of: ‘With this person on the board, what’s the likelihood of them seeing them through?’” said Mat Hope, editor of DeSmog UK.“When it comes to the consumer holding their bank card, we want to put the information out there that lets them know that these are the directors of the boards of the banks they’re banking with.”DeSmog reviewed the careers of board directors and flagged any connections with high-polluting sectors, including fossil energy, agribusiness, steelmaking and mining. The group also relied on indexes that measure polluting companies, such as the Climate Action 100 list, which includes companies like Nestlé – which has contributed to deforestation. And they reviewed links to trade groups, lobbying firms and thinktanks that have opposed climate action.JPMorgan Chase tops the list for directors with climate conflicts. All of its 10 directors have current or past ties to companies or organizations contributing to the climate crisis. Wells Fargo comes in second, with 12 out of 13 directors.Most of the seven banks declined to comment or did not respond to requests for comment. Wells Fargo noted its net-zero commitment and its plans to disclose near-term climate targets, as well as its taskforce on climate-related financial disclosures.All seven of the banks have potential climate conflicts among at least half the directors on their boards.For example, Theodore Craver, a director at Wells Fargo, is also on the board of Duke Energy, a power company that owns significant coal and gas generation. Duke has vowed to reach net-zero carbon pollution by 2050, but environmental advocates have argued the company’s plan still includes a large amount of gas. Craver is also the retired CEO of Edison International, another energy company.Michael Neal, who is on the board at JPMorgan Chase, was vice chairman of General Electric Company until his retirement in 2013.Those kinds of connections could be significant obstacles to the Biden administration’s hopes that banks will commit to climate-friendly finance, activists warn.Biden administration remains silent on Line 3 and banking conflictsJohn Kerry, Biden’s climate envoy, wants banks to commit to more near-term goals, according to Politico. But the White House has also met with environmental and watchdog groups who want the administration to be more aggressive with banks.The White House did not respond to requests to comment for this story.Collin Rees, a campaigner for Oil Change International, said advocates have consistently heard there is a desire within the White House to move forward on climate finance regulation, to require banks to have capital requirements and pass stress tests, for example.“That’s the way we would like to see it approached,” Rees said. “To talk about how we are regulating Wall Street. And to also talk about the fact that they are not only potential sources of clean energy investment, which is good, but also still driving the climate crisis.”Last week, 145 organizations wrote Kerry a letter urging him to help end “the flow of private finance from Wall Street to the industries driving climate change around the world – fossil fuels and forest-risk commodities”. They asked Kerry to “recognize that Wall Street is not yet an ally”.“As long as US firms continue to pour more money into the drivers of climate change, they are actively undermining President Biden’s climate goals,” they said.In Alida, Minnesota, Jami Gaither, a resident, pointed to a wide trench in the ground that will hold the Line 3 pipeline as the real-world effect of what banks are supporting.“This is obviously not just for one pipeline,” she said. “How much longer can we keep up this charade, this idea that we can keep going on developing fossil fuels? We’re building a fucking tar sands pipeline at the end of the world.”Disclosure: DeSmog, the group that conducted the bank analysis, is supported by the Sunrise Project, which is also a contributor to Floodlight. Read more about Floodlight’s editorial independence policies here.Catch of the Day:Fish wants you to make sure to get some sun today. And drink water (not pictured).OK, that’s all for today—thanks for reading HEATED! If you’d like to share this piece as a web page, click the button below.To support independent climate journalism that holds the powerful accountable—and to receive HEATED’s reporting and analysis in your inbox four days a week—become a subscriber today.If you’re a paid subscriber and would like to post a comment, click the “Leave a comment” button:Stay hydrated, eat plants, break a sweat, and have a great day! This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit heated.world/subscribe

Three climate feminists walk into a bar

Good afternoon everyone! Happy Monday and Happy Indigenous Peoples Day. Today being a federal holiday, I wasn’t intending to send out a newsletter. But it turns out, the newsletter I sent on Thursday—my interview with Ayana Elizabeth Johnson and Katharine Wilkinson, the editors of All We Can Save: Truth, Courage, and Solutions for the Climate Crisis—never actually sent. So I’m trying this again now, and hopefully this time it successfully hits your inboxes.One reason I probably didn’t notice Thursday’s newsletter slip by was because, real talk, these last two months have been a total brain/soul suck. Sometimes, particularly on Thursdays, I just hit send and tune alllll the way out. And I think in retrospect, last week—after that awful Vice Presidential debate—I probably just tuned out about 15 seconds too early. I need to be super *on* if I’m going to cover the climate crisis effectively every day. So in the interest of delivering on that promise, I’m going to take a small break this week. Book club will go on as planned; you’ll get discussion questions and further reading for All We Can Save on Tuesday and a new Q&A with a section author on Thursday. But I’m gonna take Wednesday off, as a birthday present to myself and all of you. (Wednesday is my 31st birthday. Please clap).In the meantime, please enjoy my interview with Ayana and Katharine about All We Can Save’s “Begin” section, which you can read in its entirety in Elle magazine. We go over the topic of “climate feminism,” what it’s like to release a climate book in the middle of a record-breaking extreme weather season, and who the best “climate dudes” are. I wish we could have had this conversation in a bar, but alas, it’s still COVID season. So we did it on the phone, and now it’s in the newsletter. The written interview below is edited and condensed for clarity, but I also uploaded the whole audio file at the top of this email, so you can listen to our conversation in its entire, unedited glory if you’d like. As always, thanks for allowing me the ability to take these small breaks when I need them. I’ll see you back in full force next week.Value interviews like this? They’re made possible by paid subscribers. HEATED is 100 percent independent and reader-funded, and every subscription makes a difference.Scene: The rage hike in Colorado when @drkwilkinson and @ayanaeliza came up with the idea for this book. It was an idea born out of our frustration that so many of the incredible women climate leaders we know don’t get the recognition they deserved or the resources they need. And born from knowing most of them won’t stop doing their critical climate work to write a book, which is still a primary path to thought leadership. So, we brought the book, the megaphone, the spotlight to them. Emily Atkin: You opened up the book by introducing the concept of climate feminism. I think that's very lovely, but there's also potential for that to be kind of risky. Just from my own experience, every time I combine climate change and feminism—even in a community as progressive as HEATED—I find myself getting some pushback from men and women who say it’s divisive in some way. I'm wondering if that jives with your experience at all. Katharine Wilkinson: Yeah, this is an interesting question. It’s making me think back to when, after the point that we could no longer make edits, Ayana and I realized: “Maybe we should have included somewhere that feminism just means gender equality?”Ayana Elizabeth Johnson: It’s on a list of possible changes to make for our next edition.KW: Feminism should not be such a loaded word. It's only a loaded word because forces have made it so, in the same way that forces have made climate change a loaded term.I would hope that people could bring their critical faculties and bullshit detectors with them beyond beyond the climate space.This is just historical reality. We started with the beginning of women's climate leadership, which starts with Eunice Newton Foote, who was both a scientist and a feminist. That is just a truth of her story. So I wonder if it will actually kind of help people to realize that actually, these two things have gone together from the beginning. And we've had now more than a century and a half to get with the program. AEJ: I would just add that at no point did we worry about this when writing the book. The only time we did was when we were deciding on the title and the subtitle. This is a book written by women, but it's a book for everyone. So we did opt not to say, like, “writings of 40 women on climate” as the subtitle—in part because we wanted something a bit more poetic—but also because we wanted everyone to pick up this book. It's the same thing we thought about when we designed a cover. We got some really pink options that we rejected.EA: No, you didn't. Really?AEJ: Oh yeah. I mean, fuchsia, but still.EA: Were there ever like, boobs on it? Or flowers? Orchids? KW: Boobs in the form of two Earths! That was one. No, not really.AEJ: I wish. But I think to your point, we certainly want everyone to feel like this book is for them. And perhaps it is the people who would most recoil from a book that mixes feminism with climate that we would most like to read the book. But we don't really have the ability to tiptoe around these issues. I will say that the essays themselves are not about feminism. It's just a book written by women. Like every essay is not about like “being a woman in climate.” They’re about farming and geo-engineering and policy and journalism. Right. So I think that's an important distinction. It's a book by women, but it's not about being women. And it's not just for women.EA: And it’s not a man-bashing book.AEJ: No. Except to the extent that some people find facts uncomfortable. The fact is that women are involved in environmental policy.That's just statistics. So if you feel bashed by facts, you might be slightly upset with the introduction. KW: And we make the point really intentionally that this is not about only women. It's about ensuring we have diverse leadership and diverse talent coming to the climate movement, and also that leadership that is more characteristically feminine and has a more feminist commitment is not limited to people of any gender. Don Cheadle and Mark Ruffalo have proclaimed themselves proud climate feminists also. EA: That’s hot. I like that. EA: I want to talk about the timing of the release of the book. When I released HEATED last year, it was September—which meant the release landed right in the middle of hurricane and wildfire season. I didn't even think about this at the time, but I think that had a big impact on how many people signed up. It was this horrifying marketing tool that I did not realize I was using. I'm wondering if if you have been experiencing a similar phenomenon. Have you been seeing people interested in this book, specifically because of the particular moment that we're in? And did you intend the release to coincide with this moment?KW: Oh my god. Yeah, I think [our marketing person] messaged Ayana at some point, saying “Oh wow, not at all intended, but I guess good work having this land in the overlap of hurricane and fire season?” Because I think we are seeing that. But our intention was twofold. One, we were trying to aim for a Climate Week release, because we figured a lot of people who are contributors above would be in New York, and we might have a chance to celebrate together. Ha-ha, not a thing anymore! And the other was that we wanted to get it out before the election. AEJ: We wanted to perhaps even influence the public discourse and make the discussion around electoral politics consider climate a bit more deeply. We also started putting this book together in December, and didn't predict that a Democratic primary would have been so focused on climate—which is obviously a wonderful relief. We had an incredible essay by Maggie Thomas, who had been Elizabeth Warren's climate adviser after being Jay Inslee’s. So we have her story about that. But yeah, our choices were basically September or February. And we just couldn't wait to get this out into the world, and busted our butts to make an entire book in nine months.KW: And that is not recommended.EA: I remember meeting you guys in New York, and seeing you guys bunkered down working in a corner in between having to do talks and network, and I was like, “This looks like it's not fun.”AEJ: It was actually such a joy. There were moments we were just like, “what were we thinking?” But almost always it was very clear to us that it was worth the effort, and that a lot of the extra work was because we tend towards the perfectionist side of the spectrum.EA: Which, honestly, those are the those are the type of people you want at the forefront of leading the response to a very complicated climate crisis. You don't want them to be like, whoops, forgot about the ocean!This question is kind of broad, but what are you individually most proud of about the book? When you hold the final product in your hands and you're flipping through what do you find yourself going to first, or feeling first?AEJ: I am most proud of how many incredible climate leaders never told their stories before, and wrote them down for this book. Like Mary Anne Hitt, who’s led the Beyond Coal campaign for a decade, which has shut down over 320 coal-fired power plants. She’s never written her story and her lessons learned. The same goes for Maggie from the [Warren] campaign, and Jacquie Patterson from the NAACP. These are people who just do the work, and don't worry about getting credit or being climate celebrities—although, they could, now that there's a weird category for that. So that brings me like a lot of joy and even pride, to know that we were a part of helping to write this little bit of history in a way and helping people to tell their own stories. KW: I am teaching the book to an undergraduate seminar course called “The Call of Climate.” And it's been really amazing to watch my students read the book, and have the “A-ha” moments from different essays. And to see them start connecting the connecting the dots through these running threads. One of my students, when we were talking about The Begin, she said “I was shaking while I read it, because I felt so empowered.”EA: Awww!!KW: The fact that there may be particularly young women who are coming to this work, and not just feeling like, “Oh, it's fine that I am a woman and I have some commitment to gender equality,” but actually realizing that will make them stronger climate leaders. I can just speak for myself and say, so much of this journey I have felt like I have silenced parts of myself, or tucked them to the side, and led with the part of me that has a doctorate. And I think that short-changed my readership. And I really hope that this book can be part of stopping the short-changing of transformational leadership going forward. Tied to that, one of the things that I really love is that this book is beautiful. The integration of these incredible, powerful essays with poetry—in some cases poetry that I have loved and felt guided by for years. I think it feels like a different kind of invitation to to the climate conversation. And I hope it will be one that reaches people who maybe haven't felt so invited by, like, reams of charts.EA: Yeah, I mean, the first thing I did when I got the book, obviously, was flipped to my own essay to see it. But next to it was this poem by Anne Haven McDonnell called, She Told Me The Earth Loves Us. And instead of reading my own essay, I read this poem like five times. And I found myself feeling very emotional, and so proud that I could have my work next to this piece. AEJ: That makes me so happy.EA: It made me really happy! And I love how the climate conversation has evolved to not only recognize, but demand our full human self. Because I feel the same way, as you said Katharine, about in the beginning [of my career] approaching this like, “I'm a science reporter, I'm an environmental reporter, I report on emissions and I'm a journalist.” And you're siloing these other parts of yourselves, like the parts that are committed to general equality, and good quality of life for everybody, and racial justice. You think, that's not that's not part of climate. If I join this movement, then then I have to silence all those other parts. I think it is really great to have a work that shows you not only that you don't have to do that, but that you really shouldn't do that. EA: You talked about about students having these “A-ha” moments. And I'm wondering if either of you had moments like that putting together this book. Were there any big “A-ha” moments where you really learned something you didn't know when you were putting it together?KW: I would say for me, one of the things that happened was there was a lot of deepening of my understanding of certain areas. Like I certainly I knew about the Beyond Coal campaign, but I did not understand the whole suite of those insights that grew out of it. I knew we needed a piece about litigation. And through that I came to a different appreciation of our bedrock environmental laws. Part of our part of our hope was that we could create a book meets the moment where people actually are hungry for more nuanced exploration of these topics. And I would say this book helped me arrive at more nuance on lots of different fronts. AEJ: We were feeling like people were ready for ready to deal with more of the complexities of climate change. So this book doesn't try to oversimplify things, although we did work really hard to eliminate all jargon, and make it accessible to everyone. This book has a lot of information, but mostly what it has is wisdom. You come away from it with a more solid grip on the truth. And with all of these pearls of wisdom, you don't come away from this book necessarily rattling off more facts—although for those who are into facts, I will say, there are a lot of them. And we marked our favorite statistics, our favorite facts, with an asterisk. So if you just want to through the book for facts, you can just look at all the asterisks.EA: My last question, if you have time, is just: If you were going to include dudes in the book, who are some of your favorite climate dudes that you would have wanted to include? AEJ: Oh man.KW: Gosh, we never even thought about it.AEJ: What I would like to see as more climate dudes championing this book, which has been not as loud as I would have liked. And that's the problem. This whole shine theory; this whole, “We're in it together;” this whole mosaic and chorus and collective approach that is stereotypically feminine—that's what we need. The climate crisis, as Katherine so perfectly puts it, is a leadership crisis. So before any of them can get in the book, I think they need to champion the collective work that the book references.I will say, Bill McKibben is a great example of that.KW: And Brian Kahn.EA: Oh yeah. Two very good ones.KW: Two very good climate dudes.EA: And Don Cheadle.KW: Yes. But yeah, we do not want this to be a book that just circulates among women and non-binary folks in the movement. There is a lot of important content here.AEJ: Climate dudes, read this book! OK, that’s all for today—thanks for reading HEATED! If you’d like to share this piece as a web page, click the button below.To support independent climate journalism that holds the powerful accountable—and to receive HEATED’s reporting and analysis in your inbox four days a week—become a subscriber today.If you’re a paid subscriber and would like to post a comment—or if you would like to view comments from paid subscribers—click the comment button:Stay hydrated, eat plants, break a sweat, and have a great day! This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit heated.world/subscribe

"Back to normal" is a death trap

Early this morning, I came across an article in Axios that I did not like. The headline: “Clean energy and climate change unlikely to lead American recovery.”Written by columnist Amy Harder, the article argues that significant climate and clean energy policy won’t make it into Congress’s next coronavirus economic relief package.“Reality check,” she writes: “Such prospects face uphill battles almost everywhere, and especially in the United States, where proponents [of solving climate change] are on defense while the Trump administration and lawmakers are in crisis mode.”I do not dislike this article because it is wrong. I dislike it because Harder is right. We are not on the path toward passing an economic recovery package that will address the next global health and economic crisis while addressing the current one.Our political leaders are about to spend trillions of public dollars on simply getting “back to normal,” when we know that “normal” is what got us into this mess. We know “normal” guarantees an imminent climate crisis, one that will cause just as much if not more health and economic devastation as COVID-19. We know “normal” is a death trap. So why are we trying so hard to go back?We’re not talking enough about the climate/COVID connection The necessity of addressing coronavirus and climate change together was not always clear. Back in March, when the virus had just started taking over America, climate activists actually encouraged people not to talk about the two issues in tandem, fearing they would be seen as opportunistic or insensitive. That didn’t seem right. After all, the climate crisis makes viral pandemics more likely to occur. Both crises threaten millions of lives and economies around the world. And climate change wasn’t taking a break for the virus; both were getting worse at the same time. So if anything, the pandemic made climate change seem more relevant, not less.That’s why, back in March, this newsletter took the opposite tack: we launched a rapid-response podcast to emphasize the connections between climate change and coronavirus. Over the course of 18 days, my podcast team and I produced and released six interviews with experts who could shed light on different aspects of the COVID/climate connection. Those interviews all served distinct purposes:* Bill McKibben of 350.org provided the overall climate activist perspective;* Kate Aronoff of the New Republic gave expert analysis of national policy and politics;* Anthony Rogers-Wright of the Climate Justice Alliance provided an overview of the effects on vulnerable communities;* Dr. Aaron Bernstein of Harvard C-CHANGE gave a rundown of the medical and scientific connections;* Mary Heglar of Columbia University dove into the emotional complexities of both crises and gave an ever deeper justice perspective;* and Ali Velshi of MSNBC spoke of the challenges of covering both crises as a mainstream journalist.The series garnered a lot of attention. It got us a feature story in the print edition of The Guardian. It got us on MSNBC, and on the Earth Day episode of public radio’s 1A, featuring EPA administrator Andrew Wheeler and former EPA administrator Gina McCarthy.Since launching, the podcast has been featured in Columbia Journalism Review; on Science Friday; on StateImpact Pennsylvania and New Hampshire Public Radio; and on PRI's The World and Living on Earth, among others. Our podcast was also featured on Spotify’s official Climate Crisis playlist (updated once a month), and people on Instagram made cool memes about it.But this clearly has not been enough. People still don’t seem to understand how inseparable these two issues are.So today, we’re releasing a 7th episode of the HEATED podcast, in an attempt to provide an overview of what we learned in episodes 1 through 6 — and in an effort to fundraise so we can make more episodes as both crises continue to unfold. Episode 7 is at the top of this email as an audio file. We also have our own feeds now on Apple and Stitcher; you can listen to it there, too, or click the button below.What we learned: It’s now or neverIn case you don’t feel like listening to the episode now, I’ll excerpt the two parts I think are the most relevant. The first part is where we talk about the biggest overall lesson we learned from doing this podcast: that it’s never been more important to talk about climate change. Because while we sit and don’t talk about climate change—while we accept going “back to normal” as a solution—the fossil fuel industry and Republicans are not trying to go back to normal. In fact, they are pushing through policies to worsen the climate crisis.The same people who have historically told us that we cannot do anything about climate change—those are the people telling us right now that “now is not the time.” And these are the same people who are themselves being opportunistic with coronavirus by not talking about climate change. They’re trapping us in the same cycle of doing what we've been doing. To go back to the way things were. But the way things were is a death trap. And the way things were is a huge profit machine for Republican lawmakers, for the fossil fuel industry, for everyone who profits off of the pandemic, and everyone who profits off of climate change. The whole concept that we shouldn't talk about climate change right now is a smash and grab for the fossil fuel industry, for the plastics industry and for everybody in power who benefits from their profits. Think of how many lives we could have saved, and think of how many millions, billions of dollars we could have saved if we started listening to climate scientists three decades ago. We literally can't afford to keep going down this path. Coronavirus is showing us that now more than ever is the time to talk about the connection between these two things. Because if we don't talk about it now, we're never gonna talk about it. We're just going to let climate change do the exact same thing coronavirus is doing to us right now, which is kill us and destroy our economy.What we learned: the community is powerfulThe second part of Episode 7 I think is most relevant is where we talk about the power of this community to shift the national conversation around climate change. Hand to heart, it’s unlike anything I’ve ever experienced in my journalism career. I finally I feel like I'm serving a community. The only time in my professional life when I ever felt close to that was when I was 20 years old, and I was reporting on state government in New York. I was covering these issues like pesticide bills that were important to mom’s groups, and domestic violence protection bills that were important to domestic workers and single parents. And it meant so much to the people who were advocating for those bills, just to see the issue in the paper, and just to get the recognition from those people that it was meaningful to them. Then I came to Washington, D.C. to do national journalism, and I felt like that purpose of fulfilling a community need almost disappeared. And it wasn't until I started the newsletter, and then this podcast, that I started to feel it again for the first time. But it wasn’t about a local issue. It was about a global issue.That's what I think is so special about this community. We've created a close knit, almost local-like community around a global issue. I don't know anywhere else where that exists. I’m not trying to pat my own back here, because it's not me, it’s everyone else. But I really find that that's the most valuable thing about this community. And the story of climate change and coronavirus isn't over. There are more chapters being written every single day, as the Trump administration writes bailouts for the fossil fuel industry; as Congress seeks to put sneaky language in economic recovery bills to prop up coal companies that have supported the Trump administration financially. And we can't cover those things without the community support.So I'm so excited that we found this niche, and this community, and that potentially we have the opportunity to keep exposing this smash and grab, to keep telling the story that they don't want us to tell. They're going to keep telling us to shut up about climate change and coronavirus. They're going to keep telling us that we're being opportunistic. They're going to keep saying that it's irrelevant. That is because they're scared of what will happen if we don't shut up.The podcast is a separate venture from the newsletter, and is 100 percent listener funded. We’d like to continue it—albeit on a much slower, more sustainable pace than the first six episodes—but we can’t do it without you. If you’d like us to keep not shutting up about the connections between COVID-19 and climate change, you can help support the podcast by clicking the button below. No matter what, though, the podcast team and I are so proud of the impact you’ve helped us make with this project. (IMO, it is probably because you have been staying so healthy and hydrated during this quarantine. Proud of you!)And I’ll always continue yelling here, podcast or no podcast, because that’s the dream.See you later! OK, that’s all for today—thanks for reading/listening to HEATED!If you liked today’s issue/episode, please feel free to forward it to a friend. If you are a paid subscriber and would like to post a comment, click the “view comments” button below:If you’ve been forwarded this email, and you’d like to support the spread of independent climate journalism that focuses on the powerful, become a subscriber today: This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit heated.world/subscribe

An interview with MSNBC's Ali Velshi

Below is a written transcript of Episode 6 of the HEATED podcast, out today on all your podcast apps, or at the audio file at the top. My guest is MSNBC anchor Ali Velshi. This is the last episode of our limited-run mini series on COVID-19 and climate change! Next week, HEATED’s publishing schedule will return back to normal. Free subscribers will get at least one email a week, and paid subscribers will get four—every morning, Monday through Thursday. I’ll make all essential COVID-19 reporting free, too.Hope you all enjoyed the series as much I enjoyed making it. Unlike the newsletter, the podcast was a team production. So if you’ve enjoyed it, and you’d like to support the four-person band behind it, consider making a donation at our GoFundme page.Enjoy the chat with Ali! Emily Atkin: Thank you for doing this. Thank you for taking some time out of your day for climate change.Ali Velshi: We should be doing it every day. So thank you for continuing to force the issue on us. I mean that in a good way, because what we tend to do in this world is jump from crisis to crisis. and it's becoming increasingly obvious that this is the one crisis that looms in the background all the time, and gets shoved out by other crises. EA: I mean, that's my whole life. Literally the only thing I do is just poke people and tell them to pay attention to climate change. AV: And this situation [with COVID-19] is interesting, right? It's the urgency. It's the unknown outcome. It's the suddenness. Suddenly, you're healthy, then you're not. Suddenly you know people who have died. So it's just this compressed timeline that we know nothing about that is scaring us. And with climate we just don't experience it the same way. EA: Yeah. There's plausible deniability with climate change. You can have a loved one die from the effects of climate change and still be able to convince yourself that it wasn't that. Whereas with coronavirus, there's no denying that’s what it is. But I want to start by having you tell listeners a little bit about your personal journey into climate reporting. We aren't seeing a lot of broadcast reporter interest in climate change. I see your interest growing. Can you just tell us a little bit about your journey to becoming someone who's interested in climate change?AV: I have a history of being a reporter who explains complicated things to people. It came from economics but it morphed into other things. And like a lot of reporters, I read and I understood climate change from the perspective of someone who reads. I certainly always thought I was on the right side of it.But probably five years ago, it became about the fact that this isn't going to inevitably solve itself. The idea that right-minded people all sort of probably shared my view, but our regulations are not built to actually acknowledge it, and our media is not built to actually acknowledge it. And so I started becoming more involved in understanding it.But it was difficult. I can explain to you why the Dow dropped a thousand points today. How do I explain to you two degrees compared to pre-industrial times in a hundred years? How do I make that understandable to people on TV? Because we have a way of doing things, and they don't lend themselves to large conceptual discussion. But then what started to happen is two things. One is the movement started to get bigger, and started to bring new people into it. It became kids teaching their parents that, “Okay, this isn't gonna change unless we're all involved in it.” And the second thing is we started to associate it with things that were urgent, that did lend themselves to television—like hurricanes, like wildfires, like flooding.And what I found was that every time I made that connection on TV, I would get people really angry at me. They'd say, this isn't the time to talk about climate. And I started to wonder: Why not? This is the only time I have your attention. And the two things are actually connected. There's real science as to the way hurricanes form now and how they develop and why temperature makes them more intense. Then people like you trying to force the discussion. There were books out there that spoke to me in my language. There were candidates who started to make this an actual priority. There were people who started to build policy around it. There were articles written that didn't feel the same. And it all came together and caused me to understand that this is my job. Being on the right side of the issue is fine. But the job is actually using your platform to express to people why something is important, and what role they might play in it, whether it's a policy role or whether it's an individual behavior role, and even what the competing interests are within those roles.EA: One of the things I've seen you do is have an increased focused on the powerful forces that have driven climate denial in our society. And I see that as an opportunity for broadcast and cable news in particular to make climate change more interesting to people—to tell the story in the language of corruption, as opposed to the language of science. Is that part of your evolution? And is that indeed an easier story to tell on broadcast?AV: It's part of my evolution in that it’s part of my evolution as a journalist. Again, probably five or six years ago, I realized that having people on TV to give you their PR-honed pitches about their business or their company is not serving my viewers interest. I would go to award ceremonies in New York for broadcasters around the world. These were people who were under threat from their governments. They would wear bulletproof vests to just do their job. And I was thinking, yeah, I don't really do a lot of that. Like I book people through their PR agencies, and they come on my show and they tell me about stuff. We call ourselves journalists, but these people speak truth to power to the extent that they endanger their lives every single day.Maybe I’m not endangering my life every day, but maybe I can actually start to say, “what can I give my viewers?” As a business journalist, most of your interviews are CEOs or marketing people. So you are just constantly being barraged by their hard sell. They spend millions of dollars being trained to deliver information, and you act as a conduit for that to your audience. And I sort of said, “This can't be what this is about.” So why not hit this disinformation part of things hard? Particularly in business journalism and economic journalism, in which lot of this climate denial is rooted. We don't do enough of a job of telling people whom we interview, holding them to the fire, because we want them to come back and interview with us again. Maybe it's my age, and how long I've been in this, but I've decided I don't need the access anymore. I don't need you to give me your interview anymore. I'm a journalist. I've actually got resources, and I've got ways in which to get to the bottom of the story. and that's how I'll do it. And if I never get a fancy interview again, or the CEO of an oil company, or a politician who wants to talk about this, that's fine. Because they've got lots of airtime. You can always hear from them. A coal company or an oil company or anyone involved with those industries—there's no time you won't get their message. You may not know that you're getting it all the time, but you're getting it. And we have to work hard to bring the other message into mainstream media. EA: Have you seen a change at all in how receptive people are at MSNBC to telling climate change stories on the air? AV: So we have a climate unit now, which we never had before. It probably corresponded with around the time that we did that presidential forum that you were at in Washington at Georgetown. So it was in the fall. And climate now doesn't seem like some weird left turn to a different discussion. We now have it as part of all policy discussions, or at least most. And that helps a great deal. You've probably seen in the last couple of weeks in mainstream media, pictures of smog that isn’t there in places where it normally is. Now, I don't think most people think, “wow, coronavirus is the solution to climate change.” But boy, that's pretty good TV. And it says, we can solve these problems. We want to solve this without it being about coronavirus—but this does mean there is proof, right? That if you stop running your engines as much, and you stop burning fossil fuels as much, some good may come of it. So let that be instructive to us.EA: It's true, but I also see some of these stories about how coronavirus is cleaning our air as a smokescreen. Not to put it so literally, but a smokescreen to what is actually happening during the pandemic, which is that we're seeing all these regulatory rollbacks on climate at the state, local and federal level—and we're not actually seeing that much coverage on it from broadcast news.[Note: In the unedited version of this interview for paid subscribers only, Velshi noted that he and Chris Hayes have covered the rollbacks—which is true! See here, here, and here.]AV: Network news has a smaller footprint. Far more viewers, but far less time to cover stories. And these things are definitely harder to get on network news. So I think that criticism is A) valid, and B) probably valid regardless because that's how these things slip through, right? That's what happens when we're all busy watching something else.There are a lot of fronts on which [loosening regulations] can make sense [during a pandemic], but that can become a slippery slope. We may allow business owners with a slightly lower-than-acceptable credit score to get a loan during this time, because if they can stay open, they can pay 10 of their employees and that's money that's not going to be used for unemployment. There's a place where we might allow some like regulatory slippage. But we have to come to terms with the fact that from a climate perspective, we’ve had decades of regulatory slippage. So we can't do that, because the regulatory stuff when it comes to climate change is the absolute lowest hanging fruit. That's the easiest stuff that we can do to get better. Even if we do all the right regulatory stuff, we still may not get to where we need to get. So we need behavioral change, we need scientific development, we need media change. But the regulatory stuff's easy. So my attitude is let's not break that. Enjoying the interview? Consider making a donation to support the team behind the HEATED podcast. There’s never been a more important time to support independent journalism, and the content you care about.EA: We have this one crisis, coronavirus, that's threatening to kill millions of people. And by loosening regulations to deal with that, we're worsening another crisis that threatens to kill more people. So in my mind, as a journalist, climate change becomes more newsworthy right now than it was before. Do you consider climate change more newsworthy or less newsworthy than usual right now?AV: I'm going to give you a very different answer to that. And that is because I'm a economic and financial journalist. And the one thing that I have been frustrated by for 25 years is that stupid Dow. The economy is such a complicated thing, and it affects people in ways that are much more sophisticated than whether the Dow was up or down 500 points. But because we have a chart, a board, a scoreboard, basically we talk about the Dow and economic numbers which come out all the time. And some are really important. But there's one that we report on all the time: The unemployment number once a month. And people get very attached to this moving number and then they get obsessed with it.Now the good and the bad about coronavirus is that there's always a chart. If you look on TV, you know how many people have it worldwide, and how many people have died. Unfortunately, it's the way we tell stories, and there's some real science to the idea that people gravitate toward colors and numbers before they gravitate toward words. And so we see these numbers, and as a result we fixate on them. We can't, in fairness, do the same thing for climate. Because the things that will kill you from climate are making some other underlying that you've got worse. Unlike Colonel coronavirus, but we don't have some scoreboard over a shorter period of time. Which again, cable news is all scoreboard over a short period of time. So one of the things I find most informative and helpful on climate, is not just the great journalism and an in-depth work that goes on, but the interactive stuff that shows people, “what will happen if you do this,” and “what will happen if you don't do this?” What are the actual effects? That's what we haven't been able to do clearly. In other words, is there a way I can have climate coverage that I can drop in no matter what else is going on in the world and make that connection? If we had a climate scoreboard—are things better or worse as a result of something that's going on right now—that would be great. But we don't think that way. It's not in our DNA enough in mainstream media to automatically say, what's the effect on climate? In the same way that I can look at anything in economics, I can look at any event and say, this is going to be bad for this company or good for that company. I can't do that yet with climate.EA: It's even hard for me at this point. I felt like I was really confident about how to make most stories really easily into a climate change story. And now with coronavirus, it's easy to see the parallels—but you don't yet have widespread public acceptance that you should be talking about this. Plus, there's a large, well-coordinated campaign to get people like me to just stop talking about climate change right now, that it’s insensitive. That’s coming straight from the president—and it's really hard to counter that narrative if you're just, like, an independent newsletter writer. It’s also hard if you're sad. And I feel like everyone who cares about climate change has a level of empathy where they're all just very sad right now.AV: Yeah. So this actually goes full circle to a question you asked a while ago. It may be easier to point out to people why certain politicians are taking that stance. Because that might be the thing that triggers the outrage, right? The person who still can't figure out anything about “parts per million” or “degrees centigrade” might still be able to figure out corruption or influence. Anybody who lived through all those years when they told us smoking was okay, they will start to understand that this is just a machine, and that machine is designed to roll over people like Emily Atkin. I mean that's what it's designed to do, right? It's mostly designed to run over people like you. And if it runs over me too in the process, that will be good.But if we can silence the voices that dig deep, then we win this battle. And that does resonate with my viewers. So where they may not understand science, or where they may not make all the connections, it definitely does resonate with them that someone is up to no good.But again, it leads you to this whole problem where you probably thought smarter people than you are in charge of this; that they'll do the right thing. And now you are clear on the fact that that's just not true. They—whoever you think “they” are—are not going to fix this, coronavirus. And they—whoever you think “they: are—are not going to fix climate change. So the takeaway for a human consumer of media today is, no one will save you. There is no one coming to save you.This is work for adults. You actually have to figure out what the right things are. We are in a world in which there is no time now for us to look for the leaders who are going to save us. So we have to look elsewhere. The evidence is there, it's available. You could subscribe to your newsletter. There are lots of books you can read. You helped me when I was preparing for that presidential forum to say, who should I be talking to? What should I be reading? What should I know? What questions should I ask? That is the work of all of us now. Me as a journalist, yes. But it's all of our work.EA: I feel like one of the other really important things is just recognizing the importance of basic science literacy. Science isn't a subject that we all need to know about, but it is something that we need our leaders to have a certain respect for.I spoke with the director of Harvard's C-Change Institute for the podcast, and he was talking about how washing your hands isn’t going to prevent the next pandemic. What's going to prevent the next pandemic is addressing biodiversity loss and the causes, which include climate change. And I'm being told this direct, scientific connection to the question that we’re all asking, which is, “how do we prevent this from happening again?” And he's just saying climate change. And I'm thinking, “why don't I see this anywhere?”AV: We’re not even there yet. We're having weird arguments that don't even settle how not to spread coronavirus from one person to the next. We're having arguments about the cure being worse than the cause, and opening up on a certain date, which was supposed to be Easter Sunday.I'm on your side on this one, but you're asking a lot. You're asking for people who are not going to have fifth grade science conversations to be having PhD science conversations. I'm with you, as we're thinking about how we're going to vote, whether it's gonna be mail in voting and term limits and campaign spending. I wish there were some kind of a thing about the scientific literacy that should play a role in our governance or at least the running of our government agencies. But we are very, very, very far from that. And I never used to think that was a bad thing, because I used to think government by the people is about people making the right choices and finding the experts who can inform them on whatever topic they need to be informed on. What I didn't realize is what happens when you actually get ignorant, right?We talk about developing herd immunity to a disease. We're developing herd ignorance. It's spreading at such a rate, and all you have to do is go on Twitter and type in “Corona virus hoax” or “lie,” and you will see the rate at which the media has bounced around on this thing and not told the right story. And unfortunately too many of our people get their information from either cable news or social media. EA: Are you telling people to not watch your platform??AV: No, I want people to watch my platform. I don't think you should only watch my platform. And I don't think anybody should take anything I say 100 percent. I think if I saw something interesting on the new, and you think I'm telling you the truth, then you need to look that up and you need to have sources that you would go to because anybody who thinks I know what I'm talking about is misinformed. I try to know what I'm doing. But this is harder than what guys like me should understand. So all I can do is point my viewer in the right direction, that this study was done by so-and-so. This article was written by so and so and you'll hear me say that on TV. I often say it, and I've said it about you, that people should follow you on social media because you need to curate your own life so that your life is not in danger. And unfortunately, this explosion of social media in the last 10 years has created a world in which your life is actually endangered because you've curated bad information.I just saw a quote from financial times saying that coronavirus is going to put a pause on anything climate related and in the policy discussions, climate's probably not going to be mentioned for the next six to 12 months.EA: Has there been any story that you've done that’s climate-related during the coronavirus crisis that you've found has particularly resonated with your audience members?AV: It's analogies rather than stories, right? It's how people tell the story. So Jake Ward, who is our tech reporter, is really great. He sort of explains it like, an inch of water can sink a battleship. You wouldn’t think it can, but it can. And that's what climate is. It's the inch of water. It's not the tsunami. One of the points that you make a lot is that we should all be doing lots of good things by the earth. This is a multi-front battle. But without dealing with the fossil fuel part of it, you can do all the other right things and you still won't get there, and I think that's the really hard one for people to understand because the fossil fuel companies have done a really good job. I'm really amazed by them actually, and somewhat impressed, at their ability to convey the message that they're on the same side as the rest of us are. They too think that there should be a carbon tax. They too think that we should tax fossil fuels at a higher rate. But they've worked it all out in a way that still will not fundamentally change the way we consume. And that I don't know that my viewers like the idea that they're being fooled. But they certainly deserve to know that they're being tricked.If you don't fix the coal and the oil and the natural gas, it's not going to stop the end of the world. It will not stop us from heating up. This starts and ends with us taking this very seriously, just like we are thinking we should do about coronavirus. So the takeaway might be that when space becomes more available for this conversation, we can start to convey to people: “You know how bad that was? That thing we just went through? That's what climate change is going to do. Times 10. It’s just not going to look as obvious to you as that one. Just look.”EA: The one thing that I've been thinking about a lot is summer. It’s coming. That means hurricanes and wildfires and flooding. I can't imagine how this will play out if we're still in a situation like we're in right now. You were an extreme weather reporter for a long time. So I'm wondering if you're thinking about the upcoming hurricane season and climate change and coronavirus coverage, and how you're thinking about approaching that as a journalist when it comes along.AV: That's a good question. I've actually talked to my bosses about this, because you know the estimates for hurricane season have come out and once again they are estimated to be more severe.We also know that climate and coronavirus affect the poor more than they affect the wealthy. That’s why this doesn’t get fixed. When rich people's houses get burned down or destroyed by hurricanes or flooded, stuff happens. Things change, code changes, buildings are put on stilts, plumbing is checked, all sorts of things happen. But because this happens to poor people as much as it does, it doesn't actually influence thought. I think that does come down to inequity. If you have money, you can mitigate these things for longer than if you don't have money. And that part of the conversation is here, and has not been squeezed out by coronavirus. It's actually been underscored by coronavirus, that poor people who live in dense populations who don't have choices, don't get to stay home. They will die at a higher rate and they don't seek healthcare. That story is another way to tell the story of climate. So if it happens, we're going to have to cover it this year, and I will be at the front end of that, but we have to start to remember the through line to all of these stories is still inequity.EA: What are you learning about these stories from covering both? Has coronavirus influenced how you think about climate change at all, or has climate change influenced how you think about coronavirus at all as a story?AV: Both stories have influenced me, but maybe coronavirus will influence my climate reporting more, in that we know, in the end, there are rights and wrongs. This coronavirus story has shown us that this wasn't inevitable. This didn't have to happen the way it happened. And we continue to hear from the administration that they did the right thing from day one. But we know they didn't do the right thing. And so it becomes very easy to call a spade a spade.And coronavirus has made that very easy and that instinct, I think it needs to stay with us for climate. We've all gotten there. You were there before. Some of us were, but many of us have gotten to the point where, let's just be honest about what this conversation is.This was not inevitable. It's not that nobody knew that climate change was a bad thing or that it was happening or that burning fossil fuels was going to be the case. Let's just be honest about it. Now let's call out those who weren't honest and let's hold those to account and let's support those who will hold them to account. If coronavirus had never hit America, it would never have been a mainstream story. But it became our story. So you can call it the Wuhan virus if you want, or the China virus. But it is our story now. That's the same thing with climate. It is our story. It's not a fringe movement. You can discount the people who are the messengers of it all you want, but the fact is it's here and it's all around you. Coronavirus allowed us to say to our viewers after every press briefing, that's just not true. You were just misled. And their bad actions have led to these outcomes. If we treated climate the same way, imagine if we were on a regular basis able to say that's not true. That's misleading. And that information has led to these outcomes. So it might give us a purity of thought around climate that I'd like to try and apply once we get a bit of an opportunity to do so.EA: I like that optimism and I liked that you came on here and shared it with us. Thanks for doing climate reporting on television. It's really cool to see and thanks for coming on this podcast and talking about it. I appreciate your insights.AV: Well, you have made a lot of us better and smarter and keep doing it and thank you for all you doing. We'll get this right eventually. OK, that’s all for today—thanks for reading (and/or listening) to HEATED!If you liked today’s issue/episode, please feel free to forward it to a friend. If you are a paid subscriber and would like to post a comment, click the “view comments” button below:If you’ve been forwarded this email, and you’d like to support the spread of independent climate journalism that focuses on the powerful, become a subscriber today: This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit heated.world/subscribe

You may also like

Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast