UN/BALANCED (private feed for pbernardi1266@gmail.com)

https://api.substack.com/feed/podcast/1070509/private/78635ee4-998f-48a3-bdf5-afcc53388d37.rssEpisode List

UN/BALANCED Episode 9: Argentina's (Lack of) Development, the Promises and Perils of Dollarization, and Pettis on Peronism

This is a free preview of a paid episode. To hear more, visit unbalancedpod.coWelcome back!Many of you know of Michael through his work on China, but before he moved to Beijing, he was in New York trading and underwriting Latin American debt. The Volatility Machine—a great book that for reasons I do not understand is now extremely expensive—was informed by those experiences. So it was great to talk with Michael about Argentina’s ongoing financial crisis and new president Javier Milei’s goal of eventually replacing the Argentine peso with the U.S. dollar.We covered a lot of ground, including the similarities between pre-Peron Argentina and the antebellum American south, development experts’ changing views of Latin America vs. East Asia, why Pettis thinks that Peronist import substitution gets a bad rap, and the political economy of debt forgiveness.Hope you enjoy! Full edited transcript below the fold.Remember, subscribers cover our cost of production. Paying listeners get to listen to the full recording and read the full transcript.Related links:Argentina and the Limits of Fiscal Space — The OvershootThe Economic Development of Latin America and its Principal Problems — ECLA (Raúl Prebisch)The Terms of Trade and the Rise of Argentina in the Long Nineteenth Century — Joseph Francis

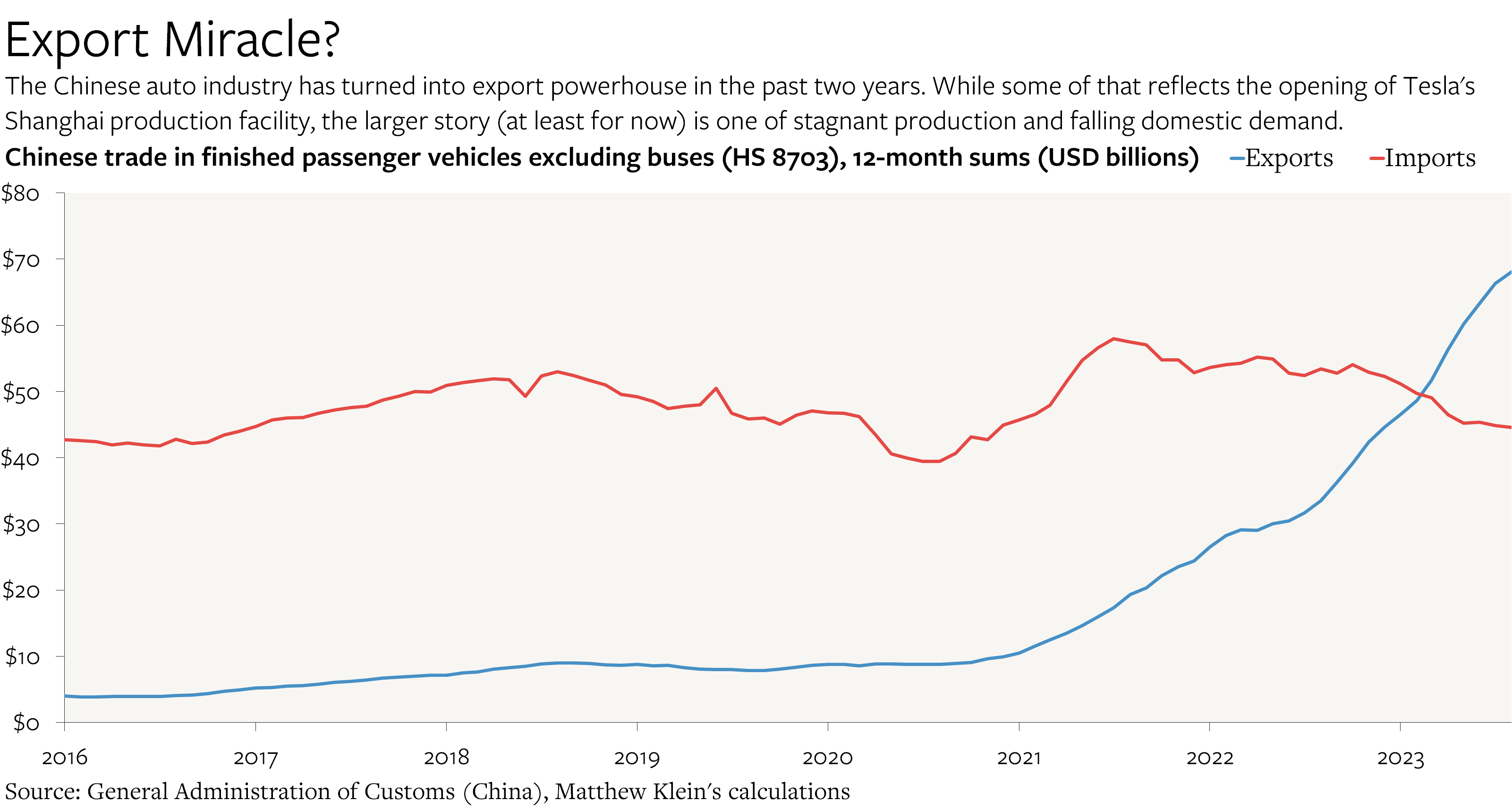

UN/BALANCED Episode 8: How China's Booming Car Exports Might Force European Rebalancing, Plus How Protection Can Work (or Not)

This is a free preview of a paid episode. To hear more, visit unbalancedpod.coWelcome back!This month’s episode digs into how China suddenly became a massive exporter of motor vehicles, swinging from a persistent pre-2021 trade deficit of around $40 billion in finished passenger cars and trucks to an annualized surplus of more than $30 billion.As in many other societies, China’s motor vehicle sector is a microcosm of the broader economy. In the Chinese case, abundant subsidies for producers have collided with weak income growth and diminished confidence among consumers, generating a surplus that is attributable to weak domestic demand rather than higher output. That has big implications for the other major motor vehicle manufacturing hubs, particularly Europe.But as we discuss, the flood of cheap Chinese electric vehicles could actually be a salutary shock if it forces Europeans to do what they should do anyway to increase their own investment and consumer spending.Hope you enjoy! Full edited transcript below the fold.Remember, subscribers cover our cost of production. Paying listeners get to listen to the full recording and read the full transcript.Related links:Danish Weight Loss Drugs vs. Chinese Cars: Two Models of Export Booms — The OvershootIn Green Tech, Overcapacity is a Boon — Martin Sandbu, FTEU Must Choose Between Cheaper Power or Protecting Wind Industry — Bloomberg

UN/BALANCED Episode 7: Europe's Crises, Dogs Getting Credit Cards, German Tourists Finally Save the World(?), and What Does "Saving" Mean, Anyway?

This is a free preview of a paid episode. To hear more, visit unbalancedpod.coWelcome back!Europe often gets left behind in discussions about the global economy, with many analysts preferring to focus on more “exciting topics” such as the U.S., China, or, sometimes, the grab-bag “emerging markets” category.But Europe is the third-largest economy in the world (second-largest until relatively recently) and has long played a major role in shaping global outcomes that affect everyone. That was why Michael and I spent so much time in Trade Wars Are Class Wars discussing Europe and how changes within Europe fit into our overall understanding of the past several decades.In this episode, we review what happened, and then continue the story to see what has changed since the pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine. The edited transcript is below the fold. Remember, subscribers cover our cost of production. Paying listeners get to listen to the full recording and read the full transcript.Related links:Europe's Imbalances in Pandemic and War — The OvershootEXPORTWELTMEISTER: GERMANY’S FOREIGN INVESTMENT RETURNS IN INTERNATIONAL COMPARISON — Franziska Hünnekes, Maximilian Konradt, Moritz Schularick, Christoph Trebesch and Julian WingenbachGlobal Imbalances Tracker — Council on Foreign RelationsDijsselbloem under fire after saying eurozone countries wasted money on ‘alcohol and women’ — Financial Times

UN/BALANCED Episode 6: China's Lackluster Reopening, What Chinese Leaders Have in Common With Herbert Hoover, Learning from Japan, and the Plunging Prestige of Architects

This is a free preview of a paid episode. To hear more, visit unbalancedpod.coWelcome back!Michael and I were not expecting to discuss China again quite so soon, but the surprising and persistent weakness of the consumption, production, trade, and investment data are all so striking that we felt compelled to dig in.We cover what Michael has been seeing on the ground, how the government might respond, the constraints facing the central government, why Richard Koo is right (or wrong) about what China can learn from Japan, why Chinese policymakers are like Herbert Hoover, what America’s recovery from Covid might teach China, the plight of China’s young graduates, and what has happened to architecture majors—among other things.The edited transcript is below the fold. Remember, subscribers cover our cost of production. Paying listeners get to listen to the full recording and read the full transcript.Related links:China's Missing Post-Pandemic Rebound—The OvershootWhy US debt will continue to rise—Michael PettisThe National Development and Reform Commission held a special press conference to introduce the promotion of private investment—NDRCNew Top Document Promoting China's Private Economy—PekingnologyRichard Koo on China's Risk of 'Japanification'—Odd LotsThe old approach to US-China relations no longer works—Stephen RoachChina Used to Be an Architect’s Dream. Now, It’s Becoming a Nightmare.—Sixth ToneMatt Klein: Hello! And welcome back to UN/BALANCED, a listener-supported podcast about the global economy and financial system. I’m Matt Klein.Michael Pettis: And I’m Michael Pettis. Today we’re going to discuss what's been happening in the Chinese economy since the end of “Covid Zero,” which was at the end of last year. Many of us, including me, were expecting a strong recovery, particularly on the consumption side. But so far that hasn’t happened. And month after month, we’ve been hit with fairly disappointing economic numbers.Matt Klein: So just to get started, maybe we can talk about what people had been thinking, and why you and others were relatively optimistic at the end of last year and the beginning of this year, which was when the government announced the end of the restrictions associated with suppressing the pandemic.Michael Pettis: During the Covid period, not just in China, but in most countries, you saw a contraction in consumption. That’s particularly important in China because consumption is already very low and consumption drives business investment. What we’d seen during the three years of Covid was a year of significant contraction in consumption that was then followed by a reasonable recovery. In 2020, Chinese GDP grew something like 3%. But consumption, along with business investment and exports, actually contracted. So more than 100% of the growth was driven by the kinds of things that China is trying to back away from: investment in the property sector and investment in infrastructure. And one of the ways we see that is that China’s debt/GDP burden worsened significantly in 2020—it went up by 25 percentage points.In 2021, however, we had a very different year. GDP growth was around 8%, but that was driven largely by a major recovery in consumption. It was not a full recovery, it was a partial recovery, but still, consumption grew by about 9%. Business investment was strong. Exports were strong. So you had pretty high quality growth. One of the things that I’ve mentioned many times before is that when the quality of growth is high, you don’t see a significant increase in the debt burden. And in fact, the debt to GDP ratio went down for the first in a very, very long time.Last year, we had another bad year. You had the terrible lockdowns, most notoriously in Shanghai, but in a lot of other places too. And once again, growth was fairly slow. The high-quality growth, which again is consumption, business investment, and exports, did quite poorly. Much of the growth was the kind of growth that, again, China doesn’t want. And once again, we saw a surge in the debt/GDP ratio, something like 12 or 13 percentage points.So many of us were expecting, not a repeat of 2021, but a partial repeat, where some of that contraction in consumption—which was a forced contraction when you’re locked at home and you simply can’t go out and consume to the same extent you used to—that some of that was going to recover this year. We’d see consumption grow reasonably quickly, not enough to make up for last year, but partially to make up for last year. And as a result, business investment would do reasonably well. So we would be able to achieve the 5% growth target quite easily. And more importantly, It's not just 5% growth or 6% growth. It would be a high-quality growth.But month after month, we’ve been very disappointed. We saw a partial recovery in February and in the beginning of March. And after that, it pretty much fizzled out. We’ve had very slow growth. And we’re seeing that in all of all of the relevant numbers. The consumption numbers are very weak. The retail sale numbers—the monthly proxy we have for consumption, because we only get consumption every three months—have been very, very weak.While the rest of the world is still dealing with inflation, China is dealing with deflation. We had a little bit of inflation in January but every month since then we’ve had deflation. Chinese exports are down a bit, but Chinese imports are down a lot. That’s another indicator of domestic consumption.All of this information is telling us the same thing: consumption simply isn’t reviving.That creates a lot of questions about what happens in the second half of the year. There are many, many people in Beijing who think that we still need to wait a little bit longer and that consumption will revive. Perhaps it will, perhaps it won’t. We don’t really know. It’s very hard to predict these things. If it does revive, we’ll probably get a partial revival in business investment. But if we don’t, we won’t. And I think most economists agree that exports are not going to grow this year because the global economy isn’t doing very well. The property sector has been badly hurt and is not going to recover.When you go through all of the possible sources of growth, there’s really only one left: renewed spending on infrastructure, which is something Beijing doesn’t want to do because China already has way too much infrastructure. And this is the big source of debt. But that’s the big question that we’re all asking ourselves: Will we see a partial revival in infrastructure spending? If that happens, that’s bad for China in the long term, but at least it delivers growth in the short term. And for political reasons and employment reasons, Beijing is very concerned about seeing an increase in economic activity over the rest of this year.Matt Klein: I definitely want to follow up on a few of those points. But before doing that, I want to highlight that this is a surprise, because a lot of the indicators one might look at—not necessarily economic indicators, but just indicators of what life is like as a person living in China today—show that there has been a tremendous normalization. Since the end of last year in terms of the experiences that normal people actually have. So I think that’s part of the reason why it’s surprising that consumption hasn’t revived. Maybe you can give us a sense of what that contrast is like and why, given this, it is so surprising that we’ve seen such a weak recovery.Michael Pettis: In many ways life seems to have gone back to normal. If you travel around Beijing, it’s full of people. There are terrible traffic jams. The subways are full, the city is full of tourists. But it’s a little bit distorted, because when you look at the various components of consumption, catering and travel have come back very strongly—that’s the number one area of growth among all the various types of consumption.Number two, interestingly enough, is gold jewelry, things like that. You sort of wonder why are people buying so much gold and jewelry. Could it be because they’re very optimistic and everyone's running around getting married and things like that? That seems unlikely. Could it be as a way, not so much of consuming, but as an alternative way of saving? We don’t really know, but we’ve seen this in the past.Automobile sales are up largely because of a lot of support from the government. But most other goods, durable goods, et cetera, are way down. So on the one hand, China looks like it’s fully recovered from “Zero Covid”, but it’s still not showing up in the in the numbers.Now, one of the things that’s been interesting to me this year is that a lot of people who weren’t able to come to China in the last 3-4 years have returned to China for visits, and I meet with quite a lot of them: academics, business people, investors, bankers, government people, et cetera, And all of them seem to think that the level of depression, the level of anxiety, the level of nervousness is much higher than they’ve ever seen before in China. It’s hard for me to tell because I’ve been here during this whole period, although it seems to me that anxiety certainly has gone up.But all of these people who haven’t been here in three or four years, were all really struck by this sense of nervousness, concern, worrying about the future.And this, of course, is something that that Beijing worries about a lot. If you’re nervous about the future, you’re unlikely to spend. If you don’t spend, we’re not going to get a recovery in the economy. And if we don’t get a recovery in the economy, of course, you’ll continue to be nervous about the future.Matt Klein: Right. There’s a real reflexivity there. It’s interesting too, because, as you said, the government in Beijing, the authorities, they do want consumer spending to rise. And you see lots of independent academics and analysts talking about this, think tankers, university deans, and people like that. It seems like there’s a consensus intellectually that there has to be more consumer spending. And yet there doesn’t really seem to be much of a policy response. I guess the People’s Bank of China sort of has been asking banks, but not asking very hard, to see if they can charge less mortgage interest on existing mortgages.But otherwise, it doesn’t seem like there’s been really kind of any major significant initiatives that match the sense of urgency or intellectual consensus that there should be more consumer spending. What’s your sense of what explains this disconnect? On the one hand, people seem to understand what's going on, there’s a belief about what should be done, but then there’s not really actually any follow through, or not much follow through.Michael Pettis: Well it’s incredibly frustrating. By now, almost everyone agrees that it’s vitally important to increase the consumption share of GDP because that’s what needs to drive growth. The two big sources of growth are consumption and investment, and there’s way too much non-productive investment in China, so you have to bring that down. But if you bring that down, either you bring up consumption or you reduce GDP growth, and of course, they don’t want to reduce GDP growth. So by a process of elimination, you must increase the role of consumption in economic activity.But there’s only two ways you can increase the consumption share of GDP in any economy: one is you can increase household debt, in other words, get households to borrow more money to consume. China did this in the last 7-8 years, to the point where household debt in China as a share of household income is among the highest in the world. It’s higher than in the U.S. Beijing is very concerned about not encouraging any additional household debt.So that leaves the only other way, which is to increase the household income share of GDP. In other words, give workers more money, improve, the pension system, reduce fees and payroll taxes. There are lots of different ways of doing it. Even make the subway free, or build cheap housing and give it to the poor, or rent it very cheaply to the poor. There’s lots of ways of doing that.But when you look at all the talk about boosting consumption—and I tell you, you can pick up the People’s Daily, and every single day there’s another article saying we are going to boost consumption—and then you read through what they’re planning to do and you see that none of them, or very, very few of those proposals actually boost household income. They’re more along the lines of “let’s make the shopping experience happier, let’s have shops stay open later at night.” Or “let’s improve delivery on the internet,” et cetera, et cetera.But the problem is that when you as a typical household think about spending money, your constraint is your income. Let’s say you have 100 of income and you decide for whatever reason that you’re going to save 15. That means you get to spend 85. And if I can figure out a more enjoyable way for you to spend that 85, you’ll be happier when you spend that 85. But you’re still not going to spend more than 85. That’s the problem. Most of the proposals are really what we would call supply side proposals, they’re not really demand side proposals.And it’s really intriguing to try to understand why that’s a problem. Part of it is institutional. But I was reading on one of my favorite topics, which is the 1930s, and as I was reading about Herbert Hoover, who was a very smart guy, but during the early days of the depression in 1930-31, he could not bring himself to deliver income to households directly.He was absolutely convinced that if you gave any money to the households that they would become “morally degenerate”. They would become “lazy”. They would stop working and you would create this big welfare class—even as household income collapsed!He was more concerned about making them “lazy” than about creating demand, so his policies were all supply side policies: “If only we can give more money to businesses, then they will go out and hire more workers and household income will go up.” The problem is that businesses couldn't sell what they were producing, and so subsidizing them further didn’t really solve the problem. They still weren’t going to hire workers. And it seems like we’ve been caught in that sort of Herbert Hoover trap here in China.Matt Klein: That’s a great point. I remember a couple of years ago when Xi Jinping introduced, or reintroduced, the concept of “common prosperity”, and then people were very excited about this. There was a lot of potential about what that could mean and how that could fit in potentially with this rebalancing agenda. And then there were these caveats of, “well, obviously, we don’t want to end up—” I think actually, you can correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe that they explicitly made comparisons to Latin America and said, “we don’t want to end up like them.”I remember being struck by that tension there. You can recognize the macro imbalance, but then you don’t want to address it because there’s a not entirely unreasonable concern about how you might affect micro behavior and incentives. But at the same time, if you let that concern get in the way too much, then you prevent yourself from doing the macro policy that you need.

UN/BALANCED Episode 5: The U.S. Banking System Reacts to Rate Hikes

This is a free preview of a paid episode. To hear more, visit unbalancedpod.coWelcome back! Apologies for the gap since episode 4. (We have a good reason, we promise.)This month we take a look back at the ructions in the U.S. banking system since early March, what they mean, and how the financial system might look different going forward as a result. Along the way we cover everything from interest rates in China to Depression-era banking regulations to central bank digital currencies.The first 15 minutes are free for everyone, but the full conversation—and full transcript—are for paying listeners. Please consider subscribing to get the full experience! As a reminder, all paid subscribers to The Overshoot are eligible for a substantial discount to paid subscriptions for UN/BALANCED.Related links:Thoughts on the Bank Bailouts — The Overshoot, March 13 2023Banks Are Blowing Up While the Economy is Strong. Time to Worry? — The Overshoot, May 10 2023Bank Regs Are Excess Profit Taxes — The Overshoot, July 20 2021How a Regulatory Tweak Will Affect Banks, Money Funds, and the Financial System — Barron’s March 26 2021Silicon Valley Bank bid report — FDICReview of the Federal Reserve’s Supervision and Regulation of Silicon Valley Bank — Michael Barr, April 28, 2023Signature Bank bid report — FDICFDIC’s Supervision of Signature Bank — FDIC, April 28, 2023First Republic Bank bid report — FDICParachute Pants and Central Bank Money — Randy Quarles, June 28 2021Economic Report of the President — Council of Economic Advisers, February 1970Thanks again to White+ for the music and to George Drake Jr. for producing!The full transcript is below, lightly edited for clarity.Matt Klein: Hello, and welcome back to UN/BALANCED, a listener-supported podcast about the global economy and the financial system. I’m Matt Klein.Michael Pettis: And I’m Michael Pettis. Today we’re going to discuss what’s been happening to the U.S. banking system as interest rates have risen and some banks have gotten into trouble. Some relatively large banks have blown up. The U.S. government has spent over $30 billion bailing out a few of the larger depositors, and a lot of surviving banks don’t seem to be in great shape.Matt Klein: But first, I would like to make a brief special announcement. As you probably have noticed, there was a longer gap than normal between our previous episode and this one, and I’m happy to say that we have a very good reason, which is that my wife gave birth to our second child back in March, shortly after we recorded the previous episode that we released in April.Everyone is doing great now, thankfully, but since the baby arrived a few weeks before her due date, we were not able to record as many episodes in advance as we’d hoped. We should be back to our regular monthly schedule from here on out. Thank you all for your understanding. Now back to the main event.Michael, we both started our careers in the midst of major banking crises, and those experiences have played a large role in our thinking and in our historical interests.Michael Pettis: Let me interrupt just so that people don’t think it was in the midst of the same major banking crisis. Your banking crisis happened much later than mine.Matt Klein: Yes, that is a fair point! Nevertheless, I do think that experience has shaped our mutual interests. Looking at this latest episode, what I find interesting is that in some respects, it perfectly fits the template of how banks get into trouble. But at the same time, in other very important respects, it’s very different from what you and I lived through in the 2000s and the 1980s.So maybe we can start by just going through kind of a quick, straightforward narrative of what actually happened with the beginning of this crisis with Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank back in March.Why did these banks blow up when they did? All banks, what do they do? They borrow from one set of customers and they lend to some other set of customers, either by making loans or by buying bonds or something like that.And the trick is to borrow from people who don’t want to get their money back anytime soon. And then you make loans to people who will pay you more because there’s some kind of risk involved. If you can manage that spread, then you make a nice profit and everyone’s happy.The problem with Signature and Silicon Valley Bank is that they ended up borrowing overwhelmingly from the types of people that are most likely to leave at the first sign of trouble.So you look at their call reports that they file with regulators and overwhelmingly they’re borrowing uninsured deposits from businesses. Not even the operating deposits that businesses use to make payroll, but the longer-term non-operating deposits.Now, if you look at what regulators say when they classify the risks of depositors and how banks and bankers should hedge against those risks and what kind of assets they should hold against those deposits, these are considered the absolute riskiest flightiest characters. And yet, these banks were holding relatively long-term assets that could not be sold on short notice without taking some kind of a loss.On top of this, and this is what I think is kind of most interesting here, is that a lot of these deposits weren't even any earning any interest. Now, in 2021 or 2020, that doesn’t really matter, right? Because the interest rates you get on short-term money were effectively zero, regardless. So if you’re getting zero interest on a bank account versus zero interest on a Treasury bill, who cares?But by the time you get to the end of 2022, the interest that you can get holding onto the safest possible short-term assets—short-term Treasury bills, or an overnight loan directly to the Federal Reserve—you can get yields of 4% or more. And yet these banks, for the most part, were still paying something on the order of zero. Maybe a little more than zero, but basically zero.So the mystery to me, in part, is: why would these business customers even keep their money there in the first place? If you’re a corporate treasurer, it is not very hard to get a better yield for your shareholders and fulfill your fiduciary responsibilities. Nevertheless, that’s the situation.Then you have a situation where both of these banks owned a bunch of bonds that were underwater in various ways, particularly Silicon Valley Bank. They had bought a lot of mortgage bonds during 2021, when mortgage bond yields were very low. Rates went up quite a bit since then, and what happened is that some depositors said, “well, this is going to be a problem.” And they start to leave the bank. The depositors see that there’s a loss, but more importantly, the bank sees that there’s a potential loss, so they try to raise capital to cover it, but then the depositors get very upset.It turns out the deposit base for Silicon Valley Bank in particular was very concentrated among startups and venture capital firms. Those venture capital firms in particular could effectively advise their startups on how to behave and what to do. And they pulled their money very quickly. The post mortem says something like 40% of their deposits left in the course of a day, before they were shut down. Banks can’t respond to that.So the interesting question here is, on the one hand, this is obviously very standard: the way banks fail is if someone stops lending to them, they fail. That’s just a very basic function of how banks are constantly borrowing. If they can’t roll over the debts, they blow up.But there’s some interesting differences here in terms of what happened.In particular, it’s not as if they took a lot of credit risk and then things blew up.That’s actually not what happened at all. They were holding very safe assets, which if they’d held to maturity, they would’ve been paid back exactly what they thought they were going to get. Yet nevertheless, they blew up. That is obviously very different from a lot of the stereotypical examples.What are you thinking of in terms of some of the historical examples that might spring to mind here? What makes this similar and what are some of the interesting differences?Michael Pettis: Traditionally there are two reasons why banks can get into trouble. One is they become insolvent and the other is that they have horribly mismatched balance sheets.In this case, there may have been an insolvency issue because the value of their assets dropped relative to the value of their liabilities. Typically, banks have insolvency issues because they make bad lending decisions. This was not a bad lending decision; this was a bad balance sheet management decision.But they always run the risk of mismatches between liabilities and assets, because it’s the job of the banks to convert short-term savings into longer-term investment. Whenever depositors want their money back—whenever the liability side of the balance sheet contracts—that puts pressure on the asset side of the balance sheet.And if the bank isn’t able to liquidate its assets very easily, which means at more or less the price at which it created them, then it gets into serious trouble.To me, the really interesting story here is the stickiness of deposits—or the lack of stickiness of deposits. I had always learned, and I’ve always taught in my banking classes—maybe I’ll teach it less, or teach it with all sorts of restrictions—that there were certain types of deposits that bankers loved. Those were basically retail deposits. And the reason they love them was because it took an awful lot to get them to move.Many banks are able to calculate what they call the “franchise value” of the deposits.If you have a lot of institutional deposits, for example, if I’m a treasurer at a company, and I deposit $100 million in your bank, that $100 million is incredibly mobile. If another bank, if a JPMorgan calls me up and says they’ll give me five basis points higher yield, it’s worth my while to take my money out of your bank and put it into another bank and to get the five basis points of higher yield. By the same token, if a friend calls me up and says, “we’re hearing rumors about your bank”, it’s worth my while to move money out as quickly as I can.But if I’m a retail depositor with $40,000 or $50,000 in the bank, it becomes much more complicated. First of all, I can’t move my money really easily. I have to take off a morning or an afternoon from work to go to the bank to move the money. This is the old days. It’s obviously not true today, but in the old days there was a cost of doing that, and my professor used to call it “shoe leather costs”. You have got to do a lot of walking around to get your money out of the bank and into another bank. So in that scenario, it would take quite a lot to get me to move my money.I would need a huge difference in interest rates; another better or equally good bank would have to offer me a lot more money before I would take my money out of the bank and move it into that bank. 1% on, on $40,000 is $400. That’s $400 in a year. That’s not nothing, but if I think that the other bank is going to catch up within a month or so, it’s hardly worth the effort to move my money out. If I hear a rumor, I’m going to need a lot more than a rumor before I’m going to go through the hassle of going to the bank, taking time off from work, going to the bank, waiting in line, et cetera, et cetera.One of the things that’s happened in recent years is that the frictional costs, or the “shoe leather cost”, of moving money around has collapsed. It’s almost zero.So now it seems to me there isn’t a huge difference between a small depositor and a big depositor in the sense that either of them can move money very quickly, very efficiently. I don’t know if you can do it in a few minutes, but certainly you can do it in less than an hour at the first sign of trouble or at the first sign of differences in interest rates, et cetera, et cetera.I’m not living in the States, I’m certainly not out in California, but it seemed to me that part of the problem may have been that this stickiness of deposits, which was a great asset for banks, has basically collapsed to zero, or close to zero, so there’s no longer any franchise value in deposits. They can move around at an incredibly rapid speed for extremely low cost, and therefore they’re much more volatile than they used to be. Would you say that that was one of the big problems with Silicon Valley Bank?Matt Klein: I think there’s an element of that. Although I also think it’s worth stressing that both Signature Bank and Silicon Valley Bank didn’t really have the kind of franchise value and deposits that we think of with a normal retail bank because they didn’t really have retail customers. In that sense not much has changed. In retrospect, I think they arguably had a negative franchise value in their deposits because of the kinds of clients that they had.But to your point, the normal default thing that makes sense is that if you’re a corporate treasurer and you’re managing large sums of cash, you would be very sensitive to differences in interest rates and risk.What’s really interesting is that in both banks, that’s not what happened. And I think the reason is that they both tried to cater to specific industry sectors and offered them services that they couldn’t get elsewhere.It’s kind of analogous to the situation you had in the 1950s or 1960s where the bank would not pay you interest, but you’d get a toaster, essentially. That’s kind of the thing that they offered, where you wouldn’t get interest—you’d be vastly underpaid compared to Treasuries or lending to the Fed or things like that—but there were other ancillary benefits.In the case of Silicon Valley Bank, they offered very favorable mortgages to rich individuals. There’s an interesting question there of individual venture partners getting a very good deal on their mortgages and then pushing all of their venture funded companies to put cash there. That’s an interesting dynamic.Signature Bank went in different direction. They really catered to the crypto industry. And they had all the systems set up that made it easier for various crypto businesses to pay each other in dollars internally through the bank. Again, that creates an interesting dynamic where, if the crypto industry tanks, as it did basically starting in the beginning of 2022, they’re pulling out their deposits for reasons totally unrelated to anything else happening.With Silicon Valley Bank as well, you had a huge influx of deposits as various venture backed companies were raising a lot of cash. And then they stopped raising cash and they started burning that cash, and that started naturally pulling deposits back. These were underlying problems.If you think about it from that perspective, the deposit franchise is negative, right? You have got yourself exposure to particular sets of financing that are not just volatile, but much more volatile than any other kind of industry, any other kind of deposit base you can think of.And those deposits are correlated in a very unfortunate way, as it turns out, with interest rates, which is also problematic if you’re using those deposits to finance longer-term debts that then lose a lot of value as interest rates rise.It’s kind of interesting to think “why would someone want to buy these businesses and assume the deposits?”The normal thing is that when a bank fails and the government steps in, or not, there’s some kind of resolution and then there’s a takeover process. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation will make sure that insured depositors get seamless transition of service. And the feeling usually is “oh, well it’s good for a bank to do that because those deposits are valuable.” As you said, retail deposits are sticky. That still seems to me mostly, in the aggregate, mostly to be the case. And yet these deposits probably are not ones you’d want.Michael Pettis: Not only are they ones that you probably wouldn’t want, but it seemed to me that Signature Bank was a particularly surprising event. During the big period of consolidation of the banks in the 1970s and 1980s, the classic argument was that small banks are overly exposed to a particular part of the economy, and so that increases the probability of default, right? If your economy, if your town does badly, the bank will collapse, and so you wanted to be diversified to protect yourself.But here it seems they were highly concentrated, not just in one particular industry, but you know, for God’s sake, perhaps the most risky industry out there, right?It’s incredible to think that no one considered the possibility that there may be a significant contraction in the crypto industry and how that would affect the balance sheet of the banks.

Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast