The Cottage (private feed for dmckenzie42@gmail.com)

https://api.substack.com/feed/podcast/47400/private/66213252-9510-40e8-8beb-adc904e5252e.rssEpisode List

VBS: The Unfinished Reformation?

A NOTE TO NEW PAID SUBSCRIBERS:WE ARE NEARING THE END OF THE SUMMER CHURCH HISTORY SERIESIF YOU ARE JUST NOW JOINING IN, you can begin here — or start with whatever you like! We’ve been going through my book, A People’s History of Christianity: The Other Side of the Story.You can watch all the previous videos, listen to the interviews with Beth Allison Barr and Jemar Tisby, read the excerpts and selections, and catch up on the lively comment sections by going to the FRONT PAGE of the Cottage website and looking for all the posts with “VBS” (Vacation Bible School 😉) in the title or subtitle. Everything is open to all paid subscribers on both the front page and in the Cottage Archive.During these thrice-a-year special series (Lent, July, and Advent), we have a modified schedule (either M,W,F or daily) with more content than usual! We’ll be back to a more regular schedule in August — along with a few special surprises. We don’t jump right into the modern world today. Instead, I take some time to reflect on the similarities of the world 500 years ago and our own situation. There’s also a nice discussion in this video of “usable” history. There might seem to be little difference between propaganda and usable history. But usable history isn’t propaganda because it is committed to telling the truth about the past. It doesn’t avoid critical history — and always stands willing to be corrected. But “usable” history does have agendas — it is an exploration of history intended to support particular issues, ideas, or communities, usually by lifting up some aspect of history that has been ignored or dismissed.At the end of today’s video lecture, I return to the Reformation itself and explain the tension between orthodoxy and orthopraxis — a binary that still haunts contemporary Christianity.I liked sharing these further thoughts on the book and the “end” of the Reformation. Hope you enjoy them too!Questions: What did you learn from this section in the reading, video presentations, or comments? What ideas or people inspire you? What surprised you?Please leave your insights in the comments! And feel free to respond to others as well.EXCERPT, A PEOPLE’S HISTORY OF CHRISTIANITY”The Unfinished Reformation,” the end of chapter 9One of my favorite professors in seminary was Richard Lovelace, a church historian with a gracious spirit. Although he served on the faculty of an evangelical theological school, he was a deeply committed mainline Presbyterian and one of the most thoroughly ecumenical people I have known. He believed that Christianity was a generous way of life, a process of on-going personal and communal reformation centered in the love of God. “Reforming doctrines and institutions in the church was futile,” he wrote, “unless people’s lives were reformed and revitalized.”[1] The reformed church, he insisted, must always be reforming. As a scholar, he studied Christian renewal movements and taught several popular classes in the history of spirituality and post-Reformation church history.Shortly after Martin Luther’s death in 1546, Professor Lovelace explained, Protestants began to fight over the particulars of their revolutionary movement. Second generation leaders demanded theological clarity and ecclesiastical order. In response, Lutherans and Calvinists developed precise systems of theology and clear boundaries as to what constituted the church. They started to fight among themselves, while, at the same time, continued to argue with Roman Catholics and Anabaptist Protestants. Instead experiencing the word as fluid, Protestant leaders made their faith rigid, concretizing the passions of their ancestors into dogmatic intellectual systems. They fought real wars—like the English Civil War or the Thirty Years’ War—over words.The post-Reformation theological turn is known as “Protestant Scholasticism,” a method “that insisted legalistically on the acceptance of precisely worded doctrinal confessions” as the basis of faith.[2] People lost the sense that words resided in human wholeness, they enlivened the heart. Theologians pitted devotion and morality against belief, thus redefining faith from a way of life into intellectual assent to certain creeds or confessions, with books filled with “quarrelling, disputing, scolding, and reviling.”[3] They used words as weapons.“By the end of the sixteenth century,” Professor Lovelace told us, “Protestants in both Lutheran and Reformed spheres were referring the ‘half-reformation,’ which had reformed their doctrines but not their lives.”[4] Hence the historical stage was set: modern Christianity would struggle between the head and the heart, orthodoxy and piety had been severed.While he lectured about this tension in the classroom, we witnessed it at the seminary. In the mid-1980s, the seminary was racked with controversy between those faculty members that insisted upon creedal purity and those committed to spiritual liveliness. The seminary “scholastics” launched a crusade against their colleagues who, in their view, were guilty of sloppy thinking or questionable orthodoxy—a charge that lead to a heresy trial, some firings, and a good many faculty retirements. For those of us who were students, it was a fearsome object lesson in church history. Inquisitions are ugly things. In the battle of orthodoxy versus piety, at my seminary at least, orthodoxy won. And, in the pitch of battle, the love of God vanished from the place.In 1675, Philipp Jakob Spener (1635-1705), a Lutheran minister, lamented the state of the church and hoped for better days, in a small book entitled Pia Desideria. Disillusioned and divided by the violence of religious wars, people found little in the church to inspire them. “There are probably few places in our church in which there is such want that not enough sermons are preached,” wrote Spener. “But many godly persons find that not a little is wanting in many sermons.” The clergy were largely trying to impress their congregations with their learning, their “suitably embellished” orthodoxy, and dry presentations of Christian teaching. Such sermons failed “to awaken the love of God and neighbor.” Spener believed that Lutheran Christians had lost their capacity to experience the transforming Word, “It is not enough that we hear the Word with our outward ear, but we must let it penetrate to our heart.” [5]Spener diagnosed the problem in simple terms: an ecclesiastical elite cared more about theological purity than the “universal priesthood” of God’s people, who constituted the real church. Leaders had directed their attention to church “disputations” and were more concerned with “human erudition” and “artificial posturing” than the pursuit of Christian wisdom. Spener warned that this turn of affairs harmed the church. Quoting one of his colleagues, Spener stated, “The consequence is that the theologia practica (that is, the teaching of faith, love, and hope) is relegated to a secondary place, and the way is again paved for a theologia spinosa (that is, a prickly, thorny teaching) which scratches and irritates hearts and souls.”[6] Why would anyone even want to be a Christian in such circumstances?So, Spener reminded his readers that “it is no means enough to have knowledge of the Christian faith, for Christianity consists rather of practice” and that “love is the real mark” of Jesus’ followers.[7] The church could never be reformed on right belief alone. Rather, “love is the whole life of the man who has faith and who through his faith is saved, and his fulfillment of the laws of God consists in love.” Christianity is not assenting to a creed, “conviction of truth is far from being faith”; but true Christianity is the “practice” of love.”[8]Not surprisingly, his “orthodox opponents” attacked him, saying that Spener’s theology was questionable because it was too subjective. It would weaken ecclesiastical authority, they warned, if the laity truly embraced his radical ideas. They accused Spener of taking the Reformation too far in letting the Word penetrate the heart.Will words prick and irritate? Will they inspire hope? Is faith a way of dogma, or a path of love? At the end of the course, Professor Lovelace asked his students, “If you have to pick, what kind of Christianity would you rather have: a Christianity with the right answers that was dead; or a Christianity, loose around the intellectual edges, that compelled people to act in love?” We sat and stared at him. No one wanted to answer. We really wanted both, but we also knew how seldom that has happened in Christian history.I hoped that Professor Lovelace’s question was relegated to the generations immediately following the Reformation—or to a cranky evangelical seminary north of Boston, Massachusetts. But the questions of the “half-reformed” Reformation still resonate. As I write, in the summer of 2008, Anglican bishops from all over the world are meeting in Canterbury having an argument over homosexuality, biblical interpretation, and the nature of the church. It is a nasty dispute, as scratchy an ecclesiastical quarrel as has ever been, made worse by instant communications and the Internet. The whole thing brings to my mind some words uttered by Martin Luther to the people of Erfurt in 1522:Beware! Satan has the intention of detaining you with unnecessary things and thus keeping you from those which are necessary. Once he has gained an opening in you of hand-breath, he will force in his whole body together with sacks full of useless questions.”[9]I don’t suppose I can do anything to quiet the din from Canterbury.But I do have an overwhelming desire to board an airplane bound for London with a suitcase full of copies of thePia Desideria.[1] Richard Lovelace, Dynamics of the Spiritual Life, p.13.[2] Peter Erb, ed., Pietists: Selected Writings (Paulist, 1983), p. 3.[3] Spener, Pia Desideria, (Fortress, 1964) p. 53[4] RL, Dynamics, p.34[5] Spener, Pia Desideria, pp. 115-117[6] Ibid., p.53.[7] Ibid., p. 95[8] Ibid., p 101, 96[9] Quoted in Spener, 51; from Luther, “Epistle or Instruction from the Saint to the Church in Erfurt,” 1522.INSPIRATIONAll praise and thanks to God most High,The Father of all Love!The God who doeth wondrously,The God who from aboveMy soul with richest solace fills,The God who every sorrow stills;Give to our God the glory!The Lord is never far away,Nor sunder'd from His flock;He is their refuge and their stay,Their peace, their trust, their rock,And with a mother's watchful loveHe guides them wheresoe'er they rove:Give to our God the glory!— Johann Jakob Schütz, “All Praise and Thanks to God Most High,” 1673Schütz was Spener’s closer friend and colleague. Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

VBS: Dr. Jemar Tisby - The Old Reformation and a New One

WE ARE AT THE SUMMER CHURCH HISTORY SERIES HALFWAY POINT!IF YOU ARE JUST NOW JOINING IN, you can watch all the previous videos, listen to the interview with Beth Allison Barr, read the excerpts and selections, and catch up on the lively comment sections by going to the FRONT PAGE of the Cottage website and looking for all the posts with “VBS” (Vacation Bible School 😉) in the title or subtitle.Jemar Tisby, my Convocation collaborator and friend, came by the Cottage and we chatted about the Reformation. Neither of us are Reformation experts — we’re both historians of American religion. But we’ve both been influenced by the Reformation and have taught it in formal and informal settings. In this discussion, we talked about what we appreciated about the theology of 500 years ago, the ways it has gone disastrously wrong, and how people long for reform could correct course. I loved the conversation. And I learned a lot about two unexpected topics: the Ten Commandments and the Westminster Confession of Faith! (Yes, mark this day: I was inspired by the Westminster Confession.)Watch the interview above. And you can read an excerpt from A People’s History below that fits with our discussion: the Reformation’s practice of teaching — the spiritual practice that linked mind and heart. TEACHINGAn Excerpt from A People’s History of ChristianityWhen I was a little girl in 1960s Baltimore, my Methodist church stood directly across the street from the neighborhood’s Catholic parish. There, on the corner of Harford Road and Echodale Avenue, the Reformation regularly replayed itself. In those last days before Vatican II, Protestants and Catholics still viewed one another with suspicion if not outright hostility, often vying for the spiritual affections of the neighborhood. No matter that we attended the same public school and shopped at the same Acme market. We lived in different religious worlds, worlds that seldom understood the other’s traditions and practices—and that competed for the neighborhood’s soul.Catechism was one such competitive practice. We Protestant children had no idea why our Catholic friends had to attend classes after school or on Saturday, when, according to our view of things, children should be roller staking on the street or playing baseball at the local field. The Roman Catholic children had to go to “catechism,” a mysterious sounding program that, we were convinced, brainwashed youngsters into a lifetime of spiritual darkness and medieval thinking. Other than the fact that catechism had something to do with First Holy Communion, the Methodists had no idea what it was. We only knew it was Roman Catholic and therefore bad. It was not something enlightened Protestant would do.By the time I was growing up, words like “catechism” and “didactic” had fallen on hard time, and Protestants generally left such moralistic forms of teaching to Catholics. Both, however, are deeply ancient teaching processes. Catechesis simply refers to oral instruction in question-and-answer form; didactic means only moral teaching. Early Christian employed both to spread the new faith—as in the Catechetical School of Alexandria or the early text of the Didache—and written catechisms were popular ways of sharing Christian theology. Ancient statements of faith like the Apostle’s Creed, now much maligned and misunderstood by contemporary people, was originally a Q-and-A catechism to prepare new believers for baptism, an oral teaching tradition that was, at some point, written down. In a pluralistic age like that of the ancient Roman Empire, teaching one’s faith was a matter of both survival and success.Throughout the Middle Ages, the Catholic church used catechisms to teach the faithful. Since most people were baptized as infants, or since the church assumed that most Europeans shared a Catholic theological outlook, catechism appeared rote—as it seemed in my childhood. It would have surprised my Methodist neighbors greatly, however, to discover that their Protestant ancestors were the very Christians who embraced and expanded the practice of catechism. When masses converted to the new faith, sixteenth century reformers understood the importance of teaching regular people the word through catechisms and creeds. They believed that the spiritual energy of the reform could not be sustained without some sort of shaping experience of God’s word through teaching.In many ways, the French Reformer, John Calvin (1509-64) acted as the great schoolmaster of the Reformer. Calvin believed that everything—nature, scriptures, and the church—was a school of Christ. While Calvin was a humanist scholar, and emphasized the importance of academic learning, he also was deeply skeptical about the human intellect to understand spiritual things. “There are many poor dunces today,” Calvin stated in a back-handed but vaguely democratic way, “who, though ignorant and unskilled use of the language, make Christ known more faithfully than all the theologians of the pope with their lofty speculation.” To him, faith resided in the heart.Because of these views, Calvin and his followers believed that every Christian—male and female, adult and child, literate or illiterate—should and could learn the faith. Most Calvinist churches included a catechism service (in addition to a regular service) on Sundays. Although this may smack of mere memorization to us, Charles Perrot, a pastor in Geneva, describes the catechism’s “echo” process as a “level” dialogue where he would “come down from the pulpit . . . and sit on a bench” with the children, having each converse with him in turn.Master. - What is the chief end of human life?Scholar. - To know God by whom men were created.Master. What reason have you for saying so?Scholar. - Because he created us and placed us in this world to be glorified in us. And it is indeed right that our life, of which himself is the beginning, should be devoted to his glory.Master. - What is the highest good of man?Scholar. - The very same thing.Master. - Why do you hold that to be the highest good?Scholar. - Because without it our condition is worse than that of the brutes.Master. - Hence, then, we clearly see that nothing worse can happen to a man than not to live to God.Scholar. - It is so.Master. - What is the true and right knowledge of God?Scholar. - When he is so known that due honor is paid to him.Master. - What is the method of honoring him duly?Scholar. -To place our whole confidence in him; to study to serve him during our whole life by obeying his will; to call upon him in all our necessities, seeking salvation and every good thing that can be desired in him; lastly, to acknowledge him both with heart and lips, as the sole Author of all blessings. To dismiss this as formulaic misses the point. Here, in a parish church in Geneva, a pastor leaves his pulpit and sits with a boy or girl, a radical egalitarian act in itself, to recite faith together. The reformers specifically rejected theological formulas and rote religion. They used catechism to personalize faith through teaching. And it is a radical expression of equality.This style can be interpreted as a “nudge” to learners to adopt reformed theology for their own—thus enabling the young “interiorize the faith” and “acquire a framework for their lives.” In addition, catechism often acted as a springboard to literacy. All of this empowered regular people—especially women, servants, and children—in faith. Teaching both transformed formed the individual and made him or her part of a larger learning community, or as the reformers put it, “a priesthood of all believers.” The reformers’ insistence on learning the word was well summed up by Ekhardt zum Drübel, a Dutch layman: “I can and may, I and every Christian, write, sing, talk, advise, speak, teach, instruct in a Christian way.” Early Protestants understood that catechism was not brainwashing, it was an oral practice of teaching that amounted to social protest.Or, as Johannes Schwöbel, a German reformer from the town of Pforzheim, stated: “The game has been turned completely upside down. Formerly one learned the laws of God from the priests. Now it is necessary to go to school to the laity and learn to read the Bible from them.”Footnotes and citations may be found in the published book.If you are interested in Dr. Tisby’s work, please check out his website for information and to sign up for his Substack newsletter, Footnotes. His recent book The Spirit of Justice, would make a great companion to our summer series.This weekend, he’s doing a three-hour training course with the King Center on non-violence. Here are the details:Train in Nonviolence from the King Center: https://store.thekingcenter.org/products/nv365-courseSaturday, July 1912 pm - 3 pm ETLive, OnlineNOTE: The registration site is for the Nonviolence365 self-paced online course. You’re in the right place. You get access to the self-paced course PLUS the live virtual experience on July 19th. The link to join the 3-hour exposure will be emailed to you.More details HERE:INSPIRATIONCalvin says if you want to encounter God, descend into yourself. Then he says if you want to understand yourself, contemplate God. He creates with this the possibility for very direct encounter between a human being and God, and holds metaphysics of what God is and what humankind are, which is again very beautiful because it’s a celebration of the brilliance of human beings….He can talk about human beings for a long time without ever mentioning sin or any of the things that are normally associated with him because he is of this renaissance humanism, the celebration.— Marilynne RobinsonI could never have dreamt that there were such goings-onin the world between the covers of books,such sandstorms and ice blasts of words,such staggering peace, such enormous laughter,such and so many blinding bright lights,splashing all over the pagesin a million bits and piecesall of which were words, words, words,and each of which were alive foreverin its own delight and glory and oddity and light.— Dylan Thomas, “Notes on the Art of Poetry”There is no Frigate like a BookTo take us Lands awayNor any Coursers like a PageOf prancing Poetry.This Traverse may the poorest takeWithout oppress of Toll;How frugal is the ChariotThat bears the Human Soul!— Emily DickinsonA Beautiful Year is coming soon! If you like today’s reflection, you’ll love the book.PREORDER NOW! Click here for more information and buying options.Subscriber note:JULY AND AUGUST are the biggest months for subscription renewals at The Cottage. Richard and I urge you to read the SUPPORT page for information about accessing your account, changing your email address, and updating your credit card (if your card was compromised in the last year or has expired, please remember to update).Our private email address is also on the SUPPORT page. Please contact us with questions. We do our very best to offer personal service, even with knotty questions.In addition, there’s a section on how to recognize the renewal charge on your credit card statement — and avoid unnecessary fraud claims (that have onerous fees charged to both parties!).I am so grateful for every single subscriber — and your presence and support are the backbone of everything that happens here. THANK YOU! Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

VBS: The Promise and Peril of Reformation

IF YOU ARE JUST NOW JOINING IN, you can watch all the previous videos, listen to the interview with Beth Allison Barr, read the selections, and catch up on the lively comment sections by going to the FRONT PAGE of the Cottage website and looking for all the posts with “VBS” (Vacation Bible School) in the title. This week, I’ll talk with historian Kristin Kobes Du Mez via a recorded video conversation about the Reformation. I can’t wait to chat with her about Calvinism! And of course I’m going to share it with you. 🙂This week, we explore the period of religious reformations in the two centuries between 1450 and 1650. The spiritual upheaval in those centuries was related to a great technological shift — the printing press. And, accompanying it, the massive expansion of literacy. Everything in Europe and Western Christianity changed. It wasn’t just in religion, but in culture, politics, economics, and understandings of human nature and human rights. If you are reading A People’s History, read the section on “The Word: Reformation Christianity” this week. Above is a video mini-lecture on the introduction — and below is an excerpt (for those of you not reading the entire book) from “Christianity as Living Words” from chapter 7.At the end of the Middle Ages, European Christians rediscovered the texts of ancient Greece and Rome. Universities started offering courses in the humane letters—that is, human literature—instead of only teaching divine things. Non-theological subjects, like poetry, oratory, and rhetoric, captured a new generation’s imagination. Students and scholars of these humane texts became known as “humanists.” Of them, historian Diarmaid MacCulloch says, “Humanists were obsessed with words and how to use them . . . (They) were lovers and connoisseurs of words.” To these late medieval people, words went beyond mere rhetoric. Words contained “power which could be used actively to change human society for the better.” A new optimism overspread Europe, as people began to sense that the world could be transformed through ancient words.Their desire to change the world through words was aided by new technology. In 1440, Johannes Gutenberg invented the first commercially viable printing press thus making books faster, easier and cheaper to produce. Once a devotional art of the monastery, bookmaking moved into the realm of industry. The new printed books found a willing audience. In cities across Europe, a new merchant class—lay people were creating new businesses in a rapidly expanding economy—was learning to read. In most European cities around 1400, only a very small percentage of people, mostly clerics, professors, and rulers, could read. In rural villages, the only literate person was often the priest. By 1650, however, literary reached as high as 80% of urban males in the city of London and rural literacy hovered around 30%. Words spread quickly beyond the controlled structures of church, university, and state through an emerging class of businessmen and burghers, and their wives and children. The more books were printed, the more the rising class aspired to read, and printers produced more books to meet the demand. Medieval people had always loved words, but social class, vocation, and technology limited the power of books. Following the invention of printing, that was no longer the case. Not since the fall of Rome could so many Europeans read. And never before did words spread so quickly to so many hearers.In many ways, the sixteenth century was an extended argument over words, the meaning of words, whose words had the greatest power, the role of words in faith, and the political impact of words. One of the first Europeans to grasp the power of words was Desiderius Erasmus (1466/9-1536), a Dutch humanist and illegitimate son of a priest, who became Europe’s first international literary celebrity. He carried on a massive correspondence with politicians and scholars across Europe, leading one contemporary historian to quip that Erasmus should be named the patron saint of networkers. He wrote bestselling guides to the humane letters—sort of Cliff Notes on literary classics—and widely read satires on monasticism and the papacy. “When I get a little money I buy books,” he confessed to a friend, “If any is left, I buy food and clothes.”Eventually, Erasmus began to apply humanist methods of critical analysis to Christian texts. He learned Greek in order to read ancient theology and the New Testament in the original language. Up until this time, most European scholars knew only Latin (the church’s language) or Hebrew (which some learned from rabbis in their communities). Knowledge of Greek had passed from western memory, leaving much of ancient Christianity known only to Eastern Orthodox scholars. Erasmus loved Greek. In 1515, some fifteen years into his study, he produced an edition of the New Testament in Greek, with critical notes and corrections of the errors he found in the Latin bible, translated by Jerome in 384.Errors? In Holy Scripture? Yes, Erasmus dared point out that, for 1,000 years, the church had been using a bible that contained mistakes. The most notable of these errors was found in Matthew 3:2, where John the Baptist cried out to the crowd, “metanoeite!” Jerome had translated this, as “Do penance!” Thus providing the biblical support for the medieval Catholic system of confession and penance for salvation. But Erasmus pointed out that the word actually meant, “Repent!” As one commentator said, “Much turned on a word.” Indeed, Erasmus overturned a tradition with a phrase, essentially questioning the entire structure of salvation. “To attack Jerome,” states Dairmaid MacCulloch, was to attack the “understanding of the Bible which the western Church took for granted.”But Erasmus was not content with a new Bible in Greek. He called for its translation into local languages, “Would that these were translated into each and every language so that they might be read and understood not only by Scots and Irishmen but by Turks and Saracens.” His project was not intended for elites, rather he envisioned the words of the Word as the common property of all: “Would that the farmer might sing snatches of Scripture at his plough and that the weaver might hum phrases of Scripture to the tune of his shuttle, that the traveler might lighten with stories from Scripture the weariness of his journey.”He even hoped women would read the New Testament for themselves.And that is pretty much how it happened. Farmers, weavers, travelers, and women picked up the book and read.When people could not read the words for themselves, others made sure they heard.What do you see as the strengths and successes of the Reformation? Of it problems and pitfalls?Do you hope for a new Reformation? What shape would it take? What do you think of my discussion of this idea in today’s video? INSPIRATIONAnd maybe it was a bar tune,Maybe not, but there we were, hunchedover too-small desks in History 101,all ninety-five freshmen humming—by need not desire—every note, every verseof Luther’s best-loved hymn, Our helper He…the right man on our side as we scribbled,hands almost numb, the body they may kill –his theology of lyrics, our theology –from age to age the same for the final questionthe spirit and the gifts are ours of the final exam,and we would win the battle, our hearts pumpingwith belief, our throats thumping with crescendo:one little word would never fell us.— Marjorie Maddox, “A Mighty Fortress” Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

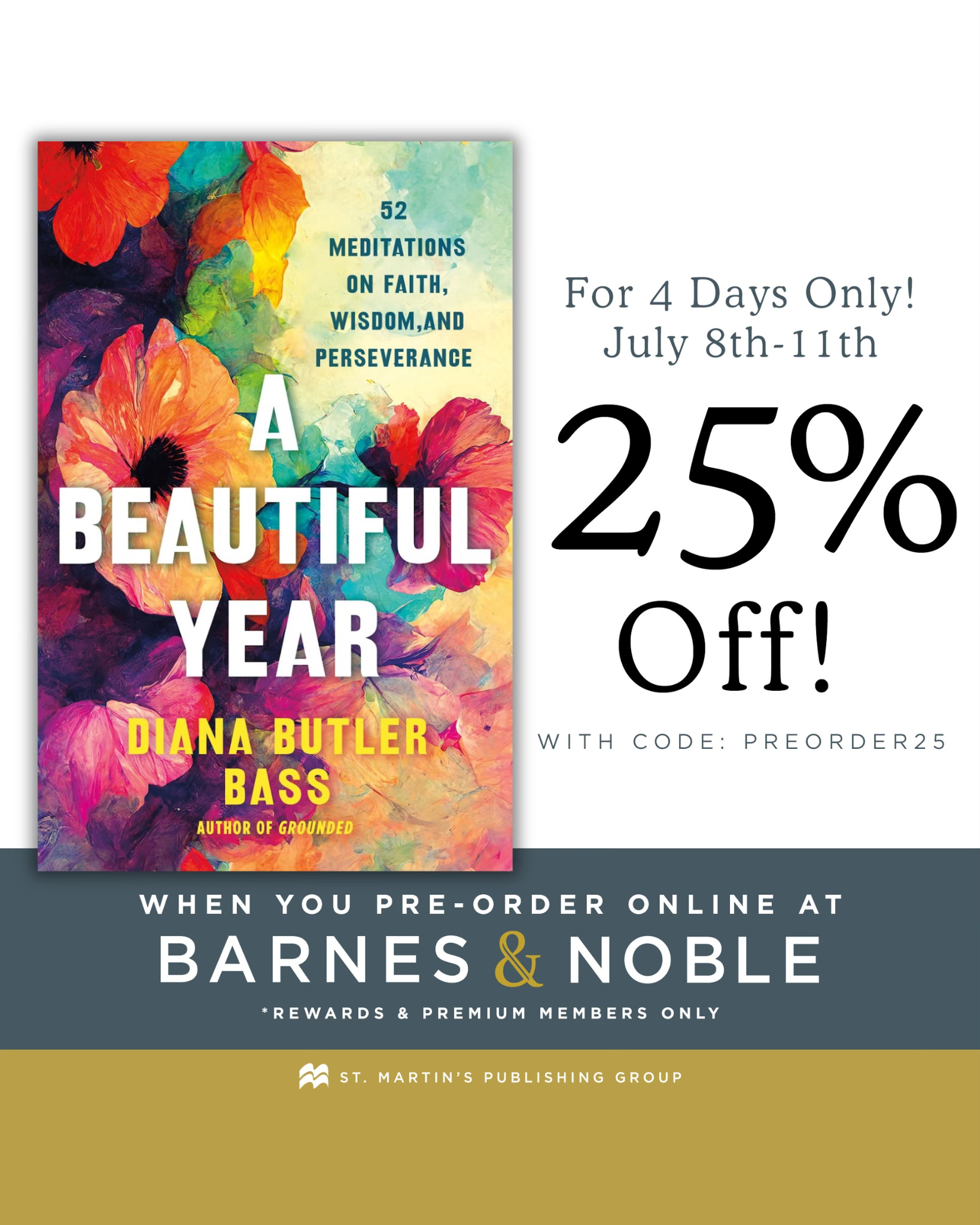

VBS: Medieval Devotion and Ethics

Today is the final day of videos on medieval Christianity. And in this one, I go rogue on the Good Samaritan! I’m not kidding. Especially if you are preaching this weekend, make sure you listen to the end.I think you’ll find this informative, thought-provoking, and relevant. Listen in as I share my enthusiasm for medieval devotional practices and what I learned from medieval “neighbor-ethics.” Yes, I know that the medieval church often failing miserably at its own test of neighbor-love. (At the end of this video, I remind us how miserably we are failing the test of neighbor-love right now. History will not treat us kindly.)The Inquisition, witch-hunts, and Crusades are evidence of that failure. There were, however, other moral paths some Christians followed. In A People’s History, I shared how some people — like Hildegard of Bingen, Francis of Assisi, Julian of Norwich, and the Beguines — wrestled with the question, “Who is my neighbor?” and their answers inspire both admiration and imitation today. I hope you’ll leave this week with a fresh appreciation of the 1,000 years — in all of its diversity and struggles — of history of the Christian church. And I hope you found some comfort in the wisdom of these folks for your life today. If you don’t have A People’s History, below are two excerpts from this section. The first is on the idea of “passion” as devotion; the second is on the moral practice of serving outcasts. The material is footnoted in the book.The Practice of Passion, Abelard and HeloiseIn my early twenties, I attended an evangelical theological school in the Boston area. A classmate, an outspoken pastor’s daughter who could have passed for Anna Nicole Smith and daringly co-registered for classes at Harvard, pinned a bumper sticker on her bulletin board offering a less-than-usual opinion in such a conservative place: “Intelligence is the Ultimate Aphrodisiac.” Not exactly a typical expression of evangelical devotion, it suggested some sort of heresy that caused me, with my own prim piety, to squirm.Whatever my response to her bumper sticker creed, however, as a church history major, I knew the sentiment described a powerful aspect of medieval Christianity, whereby doubt and love merged into spiritual passion, a way of knowing God both prized and feared by the church. While the statement did not exactly fit in the dorm, it would in a church history text. And no one better exemplified it than the twelfth-century lovers, Abelard and Heloise.Young Peter Abelard (1079-1142) arrived in Paris in 1100 to study with a master teacher, whom he quickly bested in debate. Unlike many of his contemporaries, Abelard did not subscribe to Realism, the cornerstone of medieval philosophy, which asserted that all things are grounded in some universal truth. Rather, Abelard emphasized particulars, the nuances that separate actual things from the words to describe them. Take “Humanity” as an example. What is humanity other than a collection of very different individuals? Can one even speak of universal humanity? Abelard thought not; it was only a concept, not an actuality. As one biographer said of him, “The more you concentrate on these questions, the more they slip away.” Abelard challenged medieval theology by claiming that reason could and should be applied to faith. Abelard himself would assert, “By doubting we come to inquiry, by inquiry we come to truth.”Doubting the reality behind words was one thing, but Abelard applied his method to Christian tradition. Abelard ruthlessly pointed to contradictions between particular traditions to show the folly of any universal principle of Tradition, thus opening the way for theological skepticism about everything from the lives of the saints to the doctrine of the Trinity. The result proved sensational. Students flocked to Abelard, forcing him to open a rival school, eventually exceeding other schools in enthusiasm and influence. Abelard had become an intellectual celebrity. He was more, however, than a seeker of fame or a pure skeptic. He employed doubt as a tool to find faith. If conflicts could be resolved, and contradictions synthesized, humans might discover not universal truth—but we might know the truths of the universe. Abelard did not know what those truths might be, other than having to do with God, but he was determined to find out. This quest reveals that Abelard was a man of great passion, given over, with utmost conviction, to all this exploration.At the height of his Paris career, a friend placed his niece, Heloise (ca. 1101-1162), a young woman of dubious parentage (legend identifies her mother as a nun), with Abelard to be tutored in Latin. The two began an affair, a liaison not permitted to philosophers whose intellectual purity was protected by celibacy. “So with our lessons as a pretext,” wrote Abelard, “we abandoned ourselves entirely to love.”The attraction was more than physical—Abelard and Heloise experienced an intense intellectual bond. Abelard praised her “gift for letters,” and their surviving letters attest to their mutual passion for theology, philosophy, science, astronomy, ethics, spirituality, sensuality, and sexuality. The interweaving of these things drove Abelard and Heloise to penetrating reflections on the meaning of life. “Surely I have discovered in you,” wrote Heloise, “the greatest and most outstanding good of all.” More than mere sentiment, she proclaimed that their love embodied the Aristotelian highest good, the spiritual purpose of the universe. For both, skepticism dissolved in passion—as they found God in intimacy and in the heavens, a kind of erotic cosmic oneness. They shared a “clandestine world where philosophy, love, and sex met and provided not just a shelter from the pain of the world but a key to its understanding.” A world beyond words, the ecstasy of passion, the truths of the universe.Medieval authorities praised passion when experienced by individual monks or nuns through the love of Christ, as with Francis of Assisi or Teresa of Avila, but they worried when men and women found it together, fearing that human sexuality would prove more powerful than divine love (something that Heloise herself would later admit). Their affair, which resulted in a secret marriage, became public knowledge with the birth of their son, bringing them unexpected misery. In an act of revenge, Heloise’s relatives castrated Abelard, robbing the lovers of their pleasure, thereby forcing the pair into holy orders and a life apart.These events did not end their philosophical relationship. Instead, they continued to write steamy theological missives on love’s pleasures. No doubt from his own painful experience of rough justice, Abelard rejected the idea that Christ died as a result of God’s judgment on sin. Instead, he proposed that Christ died for the sake of love, providing a model of self-sacrificial passion for humankind.Since the 19th century, romantics have interpreted Abelard and Heloise as a lovers’ tragedy. But I think it serves a more interesting purpose. Christians have often torn mind and heart asunder. Some have extolled doubt and embraced ambiguity, while others acknowledged divine love and yet denied sexual passion. Abelard and Heloise, in a strangely contemporary way, put the two together. For them, the intellectual quest and the sensual quest formed a single path back to Eden. Passion, not induced by chaste mysticism, but ignited by human hearts and rigorous inquiry opened the way to God. In the process, they envisioned Christ’s cross—the supreme Passion—as love.Imagine my surprise when, years after my friend hung her bumper sticker, I read the work of Richard Holloway, an English theologian who claims that all that is left of Christianity in the contemporary world are “doubts and loves.”Quoting the story of Abelard and Heloise to illustrate a “theology of life,” Holloway says that faith “should prompt us to live passionately and intentionally and not waste the one life we have.” I think my seminary friend may have understood this better than the rest of us.* * * * *Outcasts as Neighbors, The BeguinesFor several years, John, an acquaintance of mine was the minister of a large congregation in a gentrified area of Memphis, Tennessee. Under his leadership, the church increased its membership, added almost $500,000 a year to its pledges, doubled its endowment, and successfully navigated a political argument over gay and lesbian ordination. John was gracious person who practiced regular prayer, no scandal or impropriety marred his tenure. Yet, the congregation forced John’s resignation. Why? Because he organized a ministry offering free hot meals to the homeless and working poor in the church building once a week. Neighbors—including some congregants—protested, insisting that the program attracted both crime and unsavory characters. A task force studied options to move the program, but John stood resolute. The meal ministry would stay. Opponents were furious; proponents kept feeding the poor. The congregation almost split in the squabble. His hand forced, the pastor resigned while remaining adamant that a Christian’s primary moral duty is charity toward the poor.Charity, a word that comprises love and justice, may well be the most sublime of all Christian virtues. Of all of Jesus’ teachings and works, his compassion toward the poor, suffering, and outcast claims the admiration of those even vaguely acquainted with the Christian religion. Oddly enough, however, ministry among the meek often provokes the ire of the institutional church. And those who serve the poor are often misunderstood and persecuted.As the medieval church grew very rich, reformers like Francis of Assisi challenged the status quo with a renewed practice of both poverty and serving the poor. But the church did not embrace all such reformers as it did Francis. In the late 1100s, a loosely connected movement of laywomen, called the Beguines, and a few laymen, called Beghards, emerged in the Low Countries and the Rhineland. These laypeople engaged a semi-monastic life outside of approved convents. Mostly single, the women were “neither cloistered nuns nor married homemakers,” thus constituting an alternative female religious vocation. They lived together (occasionally women and men occupied the same houses), wore simple habits, practiced the hours, and vowed poverty and service. The women supported themselves in gender appropriate professions such as weaving, spinning (hence, “spinsters”), sewing, nursing, and teaching. One contemporary historian refers to them as “the first urban ‘base communities’ in the new urban environment.” In 1215, Pope Honorarius III approved of “pious women” living in such arrangements.Although no single theology linked all the Beguine houses in Europe, a similar impulse did: charity. At this time, most nuns were cloistered and under the authority of male superiors with their economic livings and spiritual practices essentially outside their own control. With no obligation to stay in a convent—and with no male authority confining them—the Beguines were unrestrained and could do that to which they felt called. Since they lived in common houses and worked or accepted alms, their income was freed toward whatever purpose they chose. And most of the Beguines chose to give their property away. They fed the hungry, clothed the poor, visited the sick, educated girls, offered hospitality, established homes for widows, nursed lepers, and cared for the dying. The Beguines both took alms and gave them away, thus creating a second economy, a monetary sphere outside the auspices of the institutional church.Church legislation actually prohibited women from engaging public religious work. Female spirituality was expected to be passive, not active. Writes one historian, “Neither charity nor voluntary poverty was prized above silence and obedience for women.” The Beguines, with all their conspicuous generosity, shocked other Christians by offering meals to hungry people or giving clothes to beggars. Jacques de Vitry, a sympathetic twelfth century bishop, defended them, noting:In western lands, there are innumerable communities of men and women who renounce the world and regularly live in houses of lepers and hospitals for the poor, humbly and devoutly ministering to the poor and infirm. Men and women separately and with all reverence eat and sleep in chastity. They do not omit to hear the canonical offices day and night as much as hospital work and the ministry to Christ’ poor permit . . . They take infirm people or healthy guests into their houses where they eat and sleep . . . For them, the Lord changes the filthy shit which they are forced to clear into precious stones and the stench becomes a sweet aroma.Although Bishop de Vitry referred to the Beguines as the “new mothers of the church,” their charitable acts won them few friends in the hierarchy as established clerics began to attack them.Because of their work with the poor—and in response to the criticism—some of the more outspoken Beguines blamed the social order. They connected the increase in poverty and human suffering to the growth of a moneyed class, new consumerism, and a tepid church. In her work, Mechthild of Magdeburg (c. 1212-1284) mixed mystical love poetry with apocalyptic insights and a call to reform the church—much in the same way as Hildegard of Bingen. For Mechthild, the church had failed in its vocation to love God and neighbor through the practice of virtue. Mechthild wrote of “corrupt Christianity,” referring to the “poor church” as a “maiden whose skin is filthy.” Not content to generalize, she called the local cathedral clergy “goats.” To perhaps no one’s surprise but her own, the authorities attempted to burn her books. Threatened by persecution, Mechthild fled to a convent in Helfta where some sympathetic nuns sheltered her and her writings.Mechthild’s words, and the writings of another Beguine, Hadewijch of Antwerp (no dates, mid-13th century), confirm the movement’s central spiritual insight. Love is the Christian way of life, and Jesus’ followers are called to enact his way of love. “But nowadays,” as Hadewijch stated, “Love is very often impeded, and her law violated by acts of injustice.” To Hadewijch, “brotherly love” is justice, a virtue based on respect for all human beings that serves the common good. Therefore, she asserts: “Live according to justice, not according to your pleasure or satisfaction in any way whatever.” To the Beguines, love and justice met in the practice of charity.In an age when the institutional church failed to act as Jesus toward the poor, the Beguines turned their simple program of prayer and service into a platform for church reform—hoping that their devotion to poverty and the meek would renew apostolic fervor and holy faith. They saw the clergy and the church as rich, corrupt and greedy; they identified the poor as the victims of avarice, those oppressed by wayward church leaders. In this climate, “the ideal of imitating Christ came to rest on the concept of apostolic poverty.” And charity, acts like feeding the poor, amounted to a radical reversal of the social order where those furthest from power and wealth would, indeed, inherit God’s kingdom.The authorities understood. By 1220 “religious poverty was being associated with heresy and Beguines were commonly accused of hypocrisy that amounted to heresy.” A number of church leaders condemned Beguines, ordering them to traditional convents or face the consequences. In 1311, the Council of Vienne condemned them as “an abominable sect.”And John, I am sorry to say, but it appears you are in good company.LAST DAY! DON’T MISS IT!Barnes & Noble is having a preorder flash sale for A Beautiful Year.FOUR DAYS ONLY — July 8 -11This is one of the absolute best ways to support the authors you love — preorders are key to a book’s success!Preorder my new book A BEAUTIFUL YEAR (hardcover or ebook) at bn.com from 7/8 to 7/11 and get 25% off with code PREORDER25.The direct link to the book is: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/a-beautiful-year-diana-butler-bass/1146918142?ean=9781250409881Note, this discount is only available to B&N members but free memberships are available — learn more & sign up here: barnesandnoble.com/membership/Make sure to correctly sign up and sign in for the discount. We’re not able to answer questions regarding the B&N website or their membership process.To journey with Diana Butler Bass through the seasons of the year is to see familiar scenes with fresh eyes and gather amazing insights along the way. At once a teacher and fellow pilgrim, she is a wondrous guide.— Mariann Edgar Budde, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Washington Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

VBS: A Conversation with Beth Allison Barr

Listen in for a fascinating conversation with historian Beth Allison Barr of Baylor University on medieval history. We talked about her journey from growing up Southern Baptist to teaching and researching the Middle Ages — and her obvious vocation to share her subject with her students, many of whom are from Baptist or traditionalist Catholic backgrounds. You’ll be surprised where this takes us. And you’ll learn about her favorite medieval characters along the way. I really enjoyed having her at The Cottage. I am confident you’ll find this conversation as energizing, intellectually rich, and surprisingly hopeful as I did. You can read more about Dr. Barr HERE, including information about purchasing her books. Her Substack newsletter is Marginalia, where she reflects on evangelicalism, women’s history, and Medieval history. What most surprised you in this conversation? (There’s a lot that surprised me!) Who are your medieval heroes? News from my publisher! Barnes & Noble is having a preorder flash sale for A Beautiful Year.FOUR DAYS ONLY — July 8 -11This is one of the absolute best ways to support the authors you love — preorders are key to a book’s success!Preorder my new book A BEAUTIFUL YEAR (hardcover or ebook) at bn.com from 7/8 to 7/11 and get 25% off with code PREORDER25. The direct link to my book is: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/a-beautiful-year-diana-butler-bass/1146918142?ean=9781250409881Note, this discount is only available to B&N members but free memberships are available — learn more & sign up here: barnesandnoble.com/membership/Make sure to correctly sign up and sign in for the discount. I’m not able to answer questions regarding the B&N website or their membership process.To journey with Diana Butler Bass through the seasons of the year is to see familiar scenes with fresh eyes and gather amazing insights along the way. At once a teacher and fellow pilgrim, she is a wondrous guide.— Mariann Edgar Budde, Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of WashingtonDid I mention that the book has illustrations? I’ve never written a book that is graced with artwork before! Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast