The Cottage (private feed for dmckenzie42@gmail.com)

https://api.substack.com/feed/podcast/47400/private/66213252-9510-40e8-8beb-adc904e5252e.rssEpisode List

Turn Around, Say Thanks

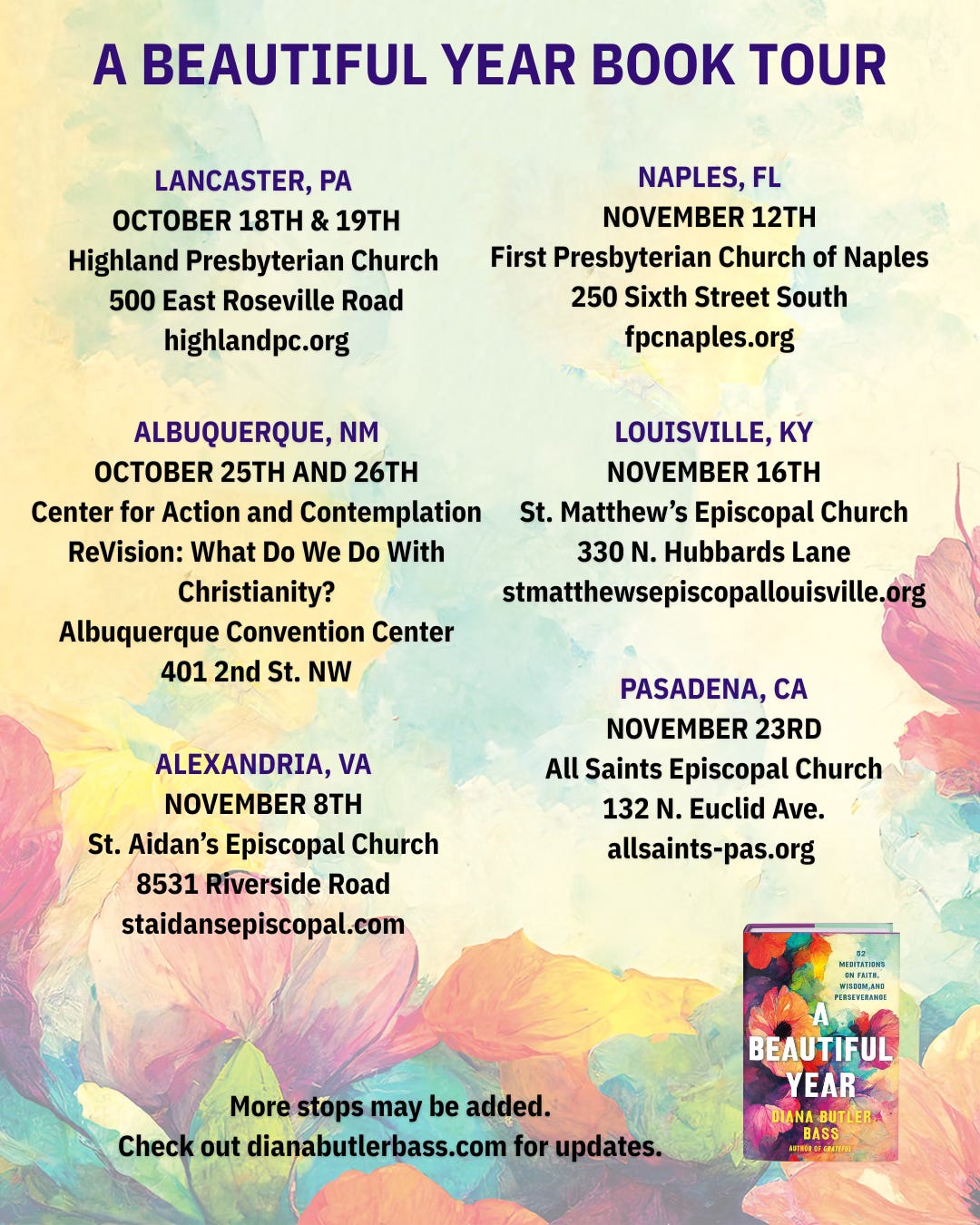

Last Sunday, I preached about gratitude — one of my favorite subjects! The sermon was a spoken version of my written musing from Luke 17:11-19, the text from October 12. Also, this musing appears in A Beautiful Year. The message is encouraging: Gifts always surround us and you don’t need to say ‘thank you.’ But being attentive to gratitude makes us whole. Gratefulness isn’t an obligation but it is a moral response to the gifts we’ve been given.Highland Presbyterian in Lancaster, PA was a full house on Sunday morning! The congregation was warm and thoughtful. I hope you enjoy listening in. It was a good morning. And, of course, it is always a good morning to consider gratitude. Enjoy listening! Hope it strengthens you today!INSPIRATIONGratitude is not a passive response to something we have been given, gratitude arises from paying attention, from being awake in the presence of everything that lives within and without and beside us. Gratitude is not necessarily something that is shown after the event, it is the deep, a-priori state of attention that shows we understand and are equal to the gifted nature of life.Gratitude is the understanding that many millions of things must come together and live together and mesh together and breathe together in order for us to take even one more breath of air, that the underlying gift of life and incarnation as a living, participating human being is a privilege; that we are miraculously, part of something, rather than nothing. Even if that something is temporarily pain or despair, we inhabit a living world, with real faces, real voices, laughter, the color blue, the green of the fields, the freshness of a cold wind, or the tawny hue of a winter landscape….Thankfulness finds its full measure in generosity of presence, both through participation and witness.— David Whyte, “Gratitude” from Consolations Please consider upgrading your subscription to support the Cottage. Thank you! New subscriptions and gift subscriptions are currently 12% off — to celebrate A Beautiful Year, my twelfth book. Things are REALLY busy right now — I’m on my way to the Southwest for a private event and then the big Richard Rohr conference, Re-Vision, where I’m speaking next Sunday morning.A Beautiful Year will be available for sale at the Re-Vision Conference. That’s the last place it can be purchased before the official release date of November 4. Get your copy early! I appreciate your prayers for safe and timely travel. Thank you!PREORDER A BEAUTIFUL YEARIf you can’t be at one of the semi-secret pre-release events, you can still preorder and get the book on its November 4 release date.Preorders are a great way to support authors, booksellers, and publishers — they help us gauge enthusiasm for a book and plan for the release. Preorders add to a book’s overall success!CLICK HERE for preorder options (from a variety of booksellers, including independents). You can preorder hardbacks, audiobooks, and e-books in a variety of formats. Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

VBS: The Summer Journey Comes to an End

Thank you so much for participating in this Cottage summertime church history journey. I hope you’ve found new inspiration and courage along the way.I hope you’ll stay around over the next months and year — you’ll be invited to my online book launch in November, have access to book previews, drop in on conversations with special guests, receive the seasonal series in Advent and Lent, and, of course, be part of a community to encourage you in these tough times.The video above is from our Cottage Zoom conversation. When we reached the end, it felt like many of you didn’t want to leave. I felt that way, too. I’m grateful for your presence in my little bookish and scribbling corner of the world. Epilogue of A People’s HistoryIn April 2008, Matthew Felling of WMAU radio in Washington, D.C., interviewed Dr. Gordon Livingston, a psychiatrist who, for more than thirty years, has been studying human happiness. Felling asked the predictable question: “What is it? What makes people happy?”Livingston responded by listing three things: meaningful work, meaningful relationships, and a sense of hope for the future. The first two are, in many ways, self-explanatory. But hope for the future? How is that achieved?“By having a realistic sense of history,” Livingston responded. He insisted that seeing the past on its own terms—not through the romantic gaze of nostalgia—is intrinsic to human flourishing. Nostalgia, he declared, is the enemy of hope. It tricks people into believing that their best days are past. A more realistic view of history, he insisted, envisions the past as a theater of experience, some good and some bad, and opens up the possibility of growth and change. Our best days are ahead, not behind. Hope for the future.There are some Christians who believe our best days are behind us — that western Christianity no longer commands the influence and respect it once did, that its churches are weakened, its message muted, and its imaginative sway on individuals and the culture diminished. In order to recapture its former glory, they insist, Christians must go back to some halcyon days when the church was orthodox, prayerful, and pure. The faith of our fathers will surely save us.Of course, no one agrees exactly what constituted this golden age since what counts as orthodoxy, spirituality, and morality have varied wildly through the last two thousand years. Exactly what are Christians nostalgic for? The early church, with its martyrs and Trinitarian formulations? Medieval Christendom with the glories of Aquinas and Chartres? The Reformation? Which one, then? The Calvinists? The Lutherans? The Anabaptists? The Anglicans? The Catholic Reformation? Perhaps the best days of the Christian faith were in the nineteenth-century when missionaries spread out over the entire globe? Or, perhaps, the best Christian world was in the 1950s, when churches were big and families were strong.A People’s History is not a nostalgia trip. In these pages, I hope it is clear that no period of church history is superior to another. Rather, each time unfolds on its own historical merits, as Christians struggle to enact Jesus’s command to love God and neighbor in a unique human context. As they wrestled with both their own world and with God, they developed particular practices of devotion and ethics. In turn, they passed these things on to their children and grandchildren who made them anew. History builds on itself. We are simultaneously just like our ancestors and completely different from them. Thus, Christianity becomes a story of accumulated human experience of God, some experiences good and some bad, that reveals a certain kind of wisdom in the world: Love is, as the Apostle Paul wrote long ago, the greatest of all things. Without love, we are, as the good apostle said flatly, “nothing” (1 Corinthians 13). And without love, Christianity is either a pretty bad joke or a twisted political agenda.“Big C” Christianity has often surrendered the pursuit of love in favor of the pursuit of its own power and perfection; Great Command Christianity grounds faith in love of God and neighbor. Because Great Command Christianity seeks not its own way, it has been harder to detect in history, but it is there. It is the undertow of those quiet souls—some named, many unnamed—who have made the world a better place as Jesus so instructed. They testify, pray, offer hospitality, feed hungry people, and visit prisoners. They challenge the church, they preach peace, and they call for justice. They are relentlessly creative, artists of tradition, who experience, as Augustine said, “beauty ever ancient, ever new.”[1] They insist that the best days for both the church and the world are ahead. They embody hope. For their trouble, they often have been branded dissenters, heretics, infidels, and witches. Occasionally, the church gets it right and makes them saints.There is a palpable longing for hope and change these days. “From the perspective of the Bible,” states Jim Wallis, “hope is not simply a feeling or a mood or a rhetorical flourish.”Hope is the very dynamic of history. Hope is the engine of change. Hope is the energy of transformation. Hope is the door from one reality to another. Things that seem possible, reasonable, understandable, even logical in hindsight . . . often seemed quite impossible, unreasonable, nonsensical, and illogical when we were looking ahead to them. The changes, the possibilities, the opportunities, the surprises that no one or very few would even have imagined become history after they’ve occurred.Between impossibility and possibility, there is a door, the door of hope. And the possibility of history’s transformation lies through that door. . . Spiritual visionaries have often been the first to walk through that door, because in order to walk through it, first you have to see it, and then you have to believe that something lies on the other side.[2]A People’s History of Christianity is, ultimately, a history of hope—that regular people often “get it” better than the rich, famous, and powerful. We see the door. We can practice God’s love and universal hospitality in a world of strangers. That is the tradition of the church—faith, hope, and love entwined, and the greatest of these is love.When I was a college professor, at the end of every church history course, I shared with my students my hope for their lives: “You have studied church history. Now, it is your turn. Go make church history.”You have studied church history. Now, it is your turn. Go make church history.[1] Quoted in Jaroslav Pelikan, The Vindication of Tradition (New Haven and London: Yale UP, 1984), 8.[2] Jim Wallis, The Soul of Politics (New York and Maryknoll, NY: New Press and Orbis, 1994), 238-240.Without love, Christianity is either a pretty bad joke or a twisted political agenda.— Diana Butler BassINSPIRATIONThe below poem by Miller Williams was written for the second inauguration of Bill Clinton in 1997. Although it is begins with the line “We have memorized America,” its vision of history is far broader and universal. We have memorized America,how it was born and who we have been and where.In ceremonies and silence we say the words,telling the stories, singing the old songs.We like the places they take us. Mostly we do.The great and all the anonymous dead are there.We know the sound of all the sounds we brought.The rich taste of it is on our tongues.But where are we going to be, and why, and who?The disenfranchised dead want to know.We mean to be the people we meant to be,to keep on going where we meant to go.But how do we fashion the future? Who can say howexcept in the minds of those who will call it Now?The children. The children. And how does our garden grow?With waving hands—oh, rarely in a row—and flowering faces. And brambles, that we can no longer allow.Who were many people coming togethercannot become one people falling apart.Who dreamed for every child an even chancecannot let luck alone turn doorknobs or not.Whose law was never so much of the hand as the headcannot let chaos make its way to the heart.Who have seen learning struggle from teacher to childcannot let ignorance spread itself like rot.We know what we have done and what we have said,and how we have grown, degree by slow degree,believing ourselves toward all we have tried to become—just and compassionate, equal, able, and free.All this in the hands of children, eyes already seton a land we never can visit—it isn’t there yet—but looking through their eyes, we can seewhat our long gift to them may come to be.If we can truly remember, they will not forget.— Miller Williams, “Of Hope and History”July and August are big renewal months at The Cottage!If you get a note from Substack about your renewal, please check your account (https://dianabutlerbass.substack.com/account) and make sure your credit card is up to date. Also, if you have a special rate, you must renew before it runs out or the fee rises.You can find any help you need on our SUPPORT PAGE or by sending an email to the.cottage.email@gmail.com.Paid subscribers have access to EVERYTHING at the Cottage, including this series, for the entire length of your subscription plan. Check out the ARCHIVE and search for a topic or biblical passage. Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

VBS: The River of Contemporary Faith

On Wednesday, July 30, I’ll host a live Zoom conversation about the summer series. Bring you questions, insights, and ideas! We’ll gather online at 4:00 PM EASTERN/1:00 PACIFIC. All paid subscribers will receive a Zoom link on Wednesday morning. July and August are big renewal months at The Cottage!I hope you’ll stay around for next year — you’ll be invited to my online book launch in November, have access to special book previews, drop in on conversations with special guests, receive the seasonal series in Advent and Lent, and, of course, be part of a community to encourage you in these tough times. Who knows what 2026 will bring?If you get a note from Substack about your renewal, please check your account (https://dianabutlerbass.substack.com/account) and make sure your credit card is up to date. Also, if you have a special rate, you must renew before it runs out or the fee rises. You can find any help you need on our SUPPORT PAGE or by sending an email to the.cottage.email@gmail.com.Paid subscribers have access to EVERYTHING at the Cottage, including this entire series, for the entire length of your subscription plan. Check out the ARCHIVE and search for a topic or biblical passage.Today’s video focuses on Chapter 13 of A People’s History, “The River.”EXCERPTIn the United States, it has become commonplace to speak of how divided our society, a fifty-fifty nation, is permanently roiled in a culture war of conservatives and liberals. Indeed, historian Patrick Allit argues that, since 1945, American Christianity has become increasingly politicized with “sharply divided” constituencies.[1] Modernity had, at its core, the presupposition that people could know religious truth—and that truth was singular, one truth for all. Thus, the modern Christian quest assumed that all right thinking—or right praying—believers could and would eventually wind up in the same place. Modern Christianity, therefore, resulted in a host of conflicts between truth claims.One of the most difficult of those arguments occurred around the turn of the twentieth century, when many Christian denominations split between Fundamentalists and Modernists. For two generations, this created a “two-party” religious squabble that pit conservatives and liberals in a battle for American souls. Churches, seminaries, and denominations split resulting in a proliferation of new churches in a society already chock-full of religious brands. North American and European missionaries exported their denominations—along with their theological quarrels—to the emerging churches in Asia, Africa, and South America. Thus, by 1900, Christianity more global than ever before, and it was more fractured and divided than it had previously been. Modern Christianity, which began with a split between Protestants and Catholics, ended with a multitude of schisms and bitter theological arguments between Christians on the basic tenets of their faith. Many historians read the latter part of the twentieth century as a continuation of this story. Social tensions abound because religion is more diverse and more politicized than ever, hardening ideological walls of separation between people.Such an interpretation, however, may depend upon whose voice one listens to.In 1913, Albert Schweitzer reflected on the modern quest for Jesus and his kingdom, with its attendant dream of oneness: “So long as we are of one will among ourselves and with him in putting the kingdom of God above all else, serving it with faith and hope, there is fellowship between him and us and with men of all races who have lived and still live guided by the same idea.” But Christians, it appeared were far from being guided by the “same idea.”Traditional sectarian divisions were complicated by the theological arguments between liberal and conservative Christians. Liberal Christianity, Schweitzer argued, had successfully navigated modern thought but had so accommodated itself that it to the spirit of the age that it may have “unstrung the bow” and teetered on becoming a “mere sociological instead of religious force;” conservatives had, by implication, proved themselves irrelevant by refusing to engage modern questions and barely figured in Schweitzer’s discussion.[2] In the process, partisan Christian lost any real sense of connection to Jesus, the “One unknown.”Schweitzer depicted Christianity of his day as “two thin streams [that] wind alongside each other between the boulders and pebbles of a great river bed,” following separate ways. No ideology, theology, or feat of ecclesiastical engineering could bring Christians back together. But Schweitzer wondered if there might come a different day, “When the waters rise and overflow the rock, they meet of their own accord.”This is how the conservative and liberal forms of religion will meet, when desire and hope for the kingdom of God and fellowship with the spirit of Jesus again govern them as an elementary and mighty force, and bring their world-views and their religion so close that the differences in fundamental presuppositions, though still existing, sink, just as the boulders of the river bed are covered by the rising flood and at last are barely visible, gleaming through the depths of waters.[3]His words strangely echoed Hildegard of Bingen’s medieval vision long of a time when “rivers of living water are to be poured out over the whole world, to ensure that people, like fishes caught in a net, can be restored to wholeness.”[4] But neither medieval Hildegard nor modern Albert Schweitzer could truly imagine such a flood might actually come.Sociologists, philosophers, and historians across argue—in surprising uniform agreement—that the West has entered some new stage of modernity, hyper-modernity, or post-modernity. In the decades since 1945, western society and culture—and the Christian religion along with it—have been transformed, not in degree but in kind. Nothing is as it was. Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman refers to the contemporary condition as “liquid modernity,” where everything “solid” has melted away. He describes “fluidity” as the “leading metaphor for the present stage of modernity.”Fluids travel easily. They ‘flow’, ‘spill’, run out’, ‘splash’, ‘pour over’, ‘leak’, ‘flood’, ‘spray’, ‘drip’, ‘seep’, ‘ooze’; unlike solids, they are not easily stopped—they pass around some obstacles, dissolve some others and bore or soak their way through others still. From the meeting with solids they emerge unscathed, while the solid they have met, if they stay solid, are changed—get moist or drenched.This situation leaves each individual in a state of radical dislocation struggling to find (if at all possible) some “new narrative” for life.[5]In each period of Christian history, particular images or orientations seem to capture the spirit of the faith. Through time, Christianity could be described as the way, a cathedral, the word, or a quest. Some scholars want to depict contemporary Christian faith as a quarrel. But I prefer to think of it as a river, water rising and overflowing its banks, a flood. A fluid faith.Schweitzer was right about floods. At the crest, water flows over the rocks—and obstacles of all sorts—merging streams into a single rushing river. Eventually, however, the water recedes leaving behind a changed landscape. The waters go down on their own accord, at their own pace, and nothing can force them to recede. If you are in a flood, you just have to wait.Since 1945, the river has been rising.[1] Allit, p. 263.[2] Schweitzer, 1910 edition, p. 402-403.[3] Schweitzer, Bowden ed., 487.[4] Quoted in Parker and Brock, Saving Paradise, p. 289[5] Zygmut Bauman, Liquid Modernity (Oxford: Blackwell, 2000), pp. 1-3.What currents can you “read” in the river right now? Who are the river guides helping you navigate the waters?INSPIRATIONI'm teaching a Health class to high schoolstudents who are not paying attention.Wandered across the hall to some lab,see Albert Schweitzer and ask for help—He wraps his arm around mine and comesto my classroom— I tell the class this isAlbert Schweitzer, Peace Nobel Laureate,and medicine man from Gabon, Africa.You may have seen him on coversof Life and Time magazines,he's an expert playing Bach on the organas well as an authority on philosophy.Those who has read Madeleine L'Engle'sA Wrinkle in Time may recognize himas a "Warrior of Light"— certainlyhe has lighted my way in science & life.The class is now quiet and attentive.Seating next to me is 80-year-old poetMargaret Mullen who tells me "Surprisedyou've invited such an important guest.I don't want to miss a single word."Schweitzer says "My specialty is tropicalmedicine. There are thousands of diseasesbut only one health. So stay healthy."— Peter Y. ChouHear our humble prayer, O God, for our friends the animals, especially for animals who are suffering; for any that are hunted or lost or deserted or frightened or hungry; for all that will be put to death.We entreat for them all Thy mercy and pity, and for those who deal with them we ask a heart of compassion and gentle hands and kindly words.Make us, ourselves, to be true friends to animals and so to share the blessings of the merciful.— Albert Schweitzer, “A Prayer for Animals”My new book, A Beautiful Year, is coming soon!Preorders help authors, book sellers, and publishers — please consider ordering now.Click here for more information and buying options. Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

VBS: The Modern Quest for the Kingdom

Paid subscribers have access to EVERYTHING at the Cottage, including this entire series, for the entire length of your subscription plan.Go to the FRONT PAGE of the Cottage website, look at recent posts, or go to the menu bar and choose ARCHIVE to find past posts. You can also learn about managing your subscription by choosing SUPPORT from the menu bar.Today’s video focuses on Chapter 12 of A People’s History, “Ethics: Kingdom Quest.”That modern pursuit of ethics centers on the theology of the Kingdom of God. This chapter explores seven social virtues that liberal Christians believed were aspects of God’s desire for “thy kingdom come, thy will be done on Earth as it is in heaven.” Those virtues include: tolerance, equality, freedom, community or “communalism,” progress, ecumenism, and pluralism. You’ll meet some amazing and brave folks in this chapter. I hope you’ll enjoy hearing and reading about them.The excerpt included today is on “Freedom” and based on the lives of Harriet Tubman and the Rev. Samuel Green. I also share from this section in the video presentation above.EXCERPTEvery summer, often on July 4, my family spends time on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, an historic and still-rural part of the state, a place noted for its small-town patriotism. Banners like “The Price of Freedom” stand guard over military cemeteries, and old “America: Love it or Leave it” bumper stickers cling to pick-up trucks. During our July 4 trip in 2008, we decided to celebrate American freedom by following the Underground Railroad trial that winds through two Maryland counties.The Underground Railroad was not a real railroad. Rather it was an underground resistance, a freedom movement empowered by a radical version of Christian faith, against slavery. In the early nineteenth century, people from a variety of denominations formed a network of safe houses and churches as an escape route for slaves from the American south to freedom. Along the routes, “conductors” provided slaves with guidance, food, and safe passage to northern free states or Canada.One of the most famous of all the conductors was Harriet Tubman (c.1820-1913), whose birthplace in Dorcester County, Maryland is marked on the trail. Born into slavery, Harriet escaped to Philadelphia in 1849. But her family remained slaves in Maryland, and Harriet felt compelled to rescue them. “I was free,” she said later, “and they should be free.” Fortified by personal experience, and by a deep sense of mystical awareness of God’s presence, Tubman believed that she should go back to help free others. Warned that her niece, Kessiah was to be sold, Tubman covertly returned to Maryland where she arranged for the young woman to escape. This began Tubman’s career as a daring conductor on the railroad, a woman on whose head authorities placed bounties totaling around $40,000. For eleven years, she returned, personally freeing more than seventy slaves. Each time, she risked her own life to help others escape. She claimed that God personally directed her journeys with spiritual promotions along the way. “I was a conductor of the Underground Railroad,” she would later state, “and I can say what most conductors can’t say—I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.” People nicknamed her “Moses.”One of the young men whom Tubman freed was named Samuel Green, Jr., who made it from Maryland to Canada in 1854. Young Green was a slave, son of a freed slave, Samuel Green (c. 1802-?), and his wife, Kitty. The elder Green may have been freed because of exemplary character—or because a sympathetic owner discerned Samuel Green had a call to the ministry. For Green, freedom in Christ equaled actual freedom. Upon leaving slavery, Green became a Methodist lay preacher and licensed exhorter, popular in the black Methodist congregations throughout Dorchester County, in the same area where Tubman was born. Eventually, Green was able to purchase his wife from slavery, but not his children. Local people held him in high esteem, “an inoffensive, industrious man; earning his bread by the sweat of his brow . . . without exciting a spirit of ill will in the pro-slavery power of his community.” Described as intelligent and literate, a white pastor commented that Green “was exceedingly useful” among black Christians, where “in their meeting-houses preached to them the word of life.”[1]When his son escaped his especially cruel master, however, local Maryland authorities began to suspect that Rev. Green was involved in the Underground Railroad (a fact that Harriet Tubman confirmed in an 1897 interview). Those suspicious, when combined with a trip to Canada to visit his son, led to Green’s arrest on April 4, 1857 on the grounds of “holding correspondence with the North.” When the sheriff searched Green’s house, where, among maps to Canada, he found a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the infamous (to southerners, at least) anti-slavery book by Harriet Beecher Stowe. Green was brought to trial for both abetting slaves and for owning the “inflammatory” book. The first charge proved difficult to prove, but the second was not. The court found him guilty of possessing an “abolition pamphlet,” and committed him to prison for ten years. The local paper, the Easton Gazette, reported that “Green was convicted simply and solely for having ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ in his possession.”[2] The pro-slavery paper then laid blame for Green’s plight on the abolitions, whose books stirred “happily contented slaves toward the troubles of freedom.”[3]Because of the danger involved, Samuel Green left little in the way of written records. Despite the fact that he could both read and write, no evidence of his involvement in the Underground Railroad remains. However, it is not hard to imagine the threat posed to the slave-holding community of a minister reading Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Green influenced hundreds of their slaves—a goodly number of whom had already escaped to freedom led by Mrs. Tubman’s visions of God. The last thing that Dorchester County appeared to need was an abolitionist Methodist preacher. One of Green’s fellow Methodists, the Reverend John Dixson Long, told the story in blunt terms, “The slaveholders of Dorchester County thirsted for an object upon which to vent their rage [following a spate of slave escapes]; hence, poor Green’s arrest and conviction.”[4]On May 18, 1857, Green entered the Maryland State Penitentiary, a facility noted for inhumane conditions. Almost immediately, abolitionists made his situation a cause celebre by insisting that Samuel Green be pardoned. Five years into his sentence, Governor Bradford finally granted Green freedom, upon the condition that he leave Maryland. Samuel Green reunited with Kitty, and the couple made their way to Canada. On the trip, he preached to various anti-slavery meetings—including one with noted abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, whereby Green noted that God was revealed in “affliction.”Green also met Harriet Beecher Stowe at her home in Hartford, Connecticut, who recorded the episode in the newspaper The Independent:There came a black man to our house a few days ago, who had spent five years at hard labor in a Maryland penitentiary for the crime of having a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in his house. He had been sentenced to ten years, but on his promise to leave the state and go to Canada, was magnanimously pardoned out. Everybody cheated him of the little property he had . . . and so he left Maryland without any acquisition except an infirmity of the limbs which he had caught from prison labor. All this was his portion of the cross; and he took it meekly, without comment, only asking that as they did not allow him to finish reading the book, we would give him a copy of Uncle Tom’s Cabin—which we did.[5]On a humid day in July 2008, my family retraced the stories of Harriet Tubman and Samuel Green as we drove through Dorchester County, Maryland.We took photos of Tubman’s birthplace and the church where Green preached.Freedom, I said to my daughter, is not an easy thing.It entails risk, especially for Christians who take its call seriously.[1] Quotes found in Richard A. Blondo, “Samuel Green: A Black Life in Antebellum Maryland (MA thesis, Uof Maryland, 1988), p. 19.[2] Quoted in ibid., p. 35-36[3] Blondo, p. 37[4] Quoted in Blondo, 50.[5] Harriet Beecher Stowe, “Simon the Cyrenian,” The Independent, NY, vol. 14, Jan-Dec 1862.INSPIRATIONHarriet Tubman didn't take no stuffWasn't scared of nothing neitherDidn't come in this world to be no slaveAnd wasn't going to stay one either"Farewell!" she sang to her friends one nightShe was mighty sad to leave 'emBut she ran away that dark, hot nightRan looking for her freedomShe ran to the woods and she ran through the woodsWith the slave catchers right behind herAnd she kept on going till she got to the NorthWhere those mean men couldn't find herNineteen times she went back SouthTo get three hundred othersShe ran for her freedom nineteen timesTo save Black sisters and brothersHarriet Tubman didn't take no stuffWasn't scared of nothing neitherDidn't come in this world to be no slaveAnd didn't stay one eitherAnd didn't stay one either— Eloise Greenfield, “Harriet Tubman”My new book, A Beautiful Year, is coming soon!Preorders help authors, book sellers, and publishers — please consider ordering now.Click here for more information and buying options. Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

VBS: Quest and the Modern World

A note: The transcription function wasn’t working last night on Substack when I edited the newsletter. Sorry that service isn’t available on this post. I hope they get it fixed soon!Paid subscribers have access to EVERYTHING at the Cottage, including this entire series, for the entire length of your subscription plan. Go to the FRONT PAGE of the Cottage website, look at recent posts, or go to the menu bar and choose ARCHIVE to find past posts. You can also manage your account from the front page under the menu bar, SUPPORT. Today’s video begins with a story about getting hit on the head — well, almost — by Protestant liberalism. After a short introduction of the period, I focus on Chapter 11 of A People’s History, “Devotion: The Quest for Light.”That modern quest centers on the question, “Where is God?” The chapter covers seven modernist answers: God is the inner light (the Quakers); God can be found in the light of learning (Sister Juana Ines de las Cruz); God can only be discovered in the new light of conversion (Wesley and the Methodists); God is present in the light of Reason, or Enlightenment (Thomas Jefferson); God’s mystery can be experienced in the light of nature (Emerson and the Transcendentalists); God is everywhere, because light is everywhere (Bushnell and liberalism); and maybe we just can’t know (Emily Dickinson). The excerpt included today is the “Light of Learning” based on the story of a Mexican nun, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. There’s also a poem by her at the end of today’s post. EXCERPT, “Light of Learning: The Catholic Vision”It is striking how many college seals are designed with pictures of lamps, candles, stars, and the rays of the sun. Such depictions, of course, equate light with knowledge. An educated person is an enlightened person. From a Christian perspective, the symbolism is rich. For “light” is more than factual knowledge. Indeed, Christ is understood to be the Light of the World, a symbol of both spiritual and intellectual enlightenment. Thus, for most of Christian history, learning and faith were intertwined, the two paths were really one.But the double journey of knowledge generally had been reserved to male clerics, philosophers, and lawyers. Few women could read. At the Reformation, that began to change as a powerful reorientation toward the written word swept through Europe. God’s light, it appeared, could be found in books. Laymen learned to read, and eventually, laywomen as well. The new learning was not only a Protestant phenomena, but Roman Catholics embarked on modern quest to find God through learning as well—something that had occasionaly been resisted by the church. In modernity, Protestants and Catholics approached learning differently. Protestants tended to read the Bible so that they might understand the world; Catholics generally reversed this, seeking to learn about the world in order to understand the Bible.Inés Ramirez de Asbaje y Santillana (1651-95) was born on a ranch southeast of Mexico City. She was, most likely, illegitimate and was raised by her grandparents. As a young girl, she displayed a precocious intellect and learned to read before she was six. Her grandfather owned a substantial library—and Inés had to be physically restrained from keeping her away from his books. Because of her obvious talent, she was sent to Mexico City to live at the viceroy’s court. Her family wished her to marry well, but Inés embraced celibacy and scholarship instead. “Give the total antipathy I felt toward marriage,” she wrote, “I deemed convent life the least unsuitable and most honorable I could elect . . . Such as wanting to live along, and wishing to have no obligatory occupation to inhibit the freedom of my studies.”[1] She entered a convert and took the name, Juana Inés de la Cruz.The convent was not particularly rigorous. There, Juana could pursue her interests. She wrote poetry, carols, and plays, studied science and philosophy, and read and collected thousands of books in Latin, Spanish, and Portuguese. Juana gained fame for her intellect, was christened the “Tenth Muse” of New Spain, was held court at the convent with nobles, political leaders, and intellectuals, many of whom corresponded with her on a regular basis. The new viceroy and his wife (to whom Juana would write erotic love poetry) befriended her and acted as her patrons.Sometime in the 1680s, Juana wrote El Sueño (English, The Dream), a poem extolling the soul’s desire for knowledge. Composed for her own pleasure, she describes learning as a fearsome quest wherein, “reason ignobly flees from confrontation,” and “comprehension turns away, dismayed whole, dreading failure, acumen evades the daunting challenge.” Despite such intimidation, Juana went on to say that “it seemed faint-hearted meekly to yield the laurel wreath before the battle started.” So, she persevered to find the light that infused the world:. . . while our Hemisphere was inundatedby a flood of gold that radiatedfrom a solar aureole that impartially restoredcolor to all things visible, andgradually,reactivated the externalsenses, an affirmation that leftthe World illuminated, and me awake.[2]The poem is compelling, the testimony of a nun, a Mexican women finding the light in the New World. In a very real sense, throughout her work, the light has passed from the institutions of the Old World to the peoples and geography of the New. And, interestingly enough, the light was not particularly supernatural or mystical. Rather, it was found in her immediate experience of nature through human senses. In making this move, Juana shifted the Catholic emphasis on learning away from the illuminating word to “the world illuminated.”All of this worried church authorities fearing both her political influence and her powerful intellect. Her first confessor worried that her poetry was too secular and ordered her to stop writing. She dismissed him. Attempting to control her, the bishop published one of her private letters—it criticized a priest’s sermon—and called upon her to cease her studies and embrace the more feminine vocation of silent prayer.Juana responded vigorously, claiming that her studies were her attempt to understand “the eminence of sacred theology,” the discipline that Catholics considered to be the “queen” of the sciences.[3] Defending her scholarly pursuits, she asked, “How can one who has not mastered the style of the ancillary branches of learning hope to understand that of the queen of them all?” To Juana, rhetoric, physics, music, mathematics, architecture, law, history, and astronomy all figured in Holy Scripture—and without knowledge of each of these fields, the Bible could not be properly understood. “In sum,” she argued back to the bishop, “how to understand the book which takes in all books, and the knowledge which embraces all types of knowledge, to the understanding of which they all contribute?”[4] Studying was a religious vocation. The church did not protest that point. They disliked both her method and the fact that a woman employed it. Juana’s approach was bottom-up. Secular learning led to holy understanding, not the other way around. “Continuing prayer and purity of life” must compliment mastery of the natural world, but only a combination of the two led to the “illumination of the mind” that amounted to wisdom.In a bold move, Juana accused the bishop of persecuting her for her “love of learning and letters.” The quarrel lasted five years. The church opened an investigation into her conduct. In 1694, she appears to have been forced to sign documents of contrition, give away her library, and abandon scholarship. She died a year later. Although the church treated her unjustly, the modernist impulse to find God through studying human sciences would expand in Catholic thought and piety. Modern Catholic education would, in many cases, be more open to new knowledge in the arts and sciences than some forms of Protestantism.Where is God? Pick up a book—any book—and read.[1] Quoted in McNamara, Sisters in Arms, p. 539[2] Juana Ines de la Cruz, El Sueno, excerpts, http://home.infionline.net/~ddisse/juana.html[3] Juana Ines de la Cruz, Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz, in Amy Oden, ed., In Her Words, p. 240.[4] Ibid., 241-242INSPIRATIONYou foolish men who laythe guilt on women,not seeing you’re the causeof the very thing you blame;if you invite their disdainwith measureless desirewhy wish they well behaveif you incite to ill.You fight their stubbornness,then, weightily,you say it was their lightnesswhen it was your guile.In all your crazy showsyou act just like a childwho plays the bogeymanof which he’s then afraid.With foolish arroganceyou hope to find a Thaisin her you court, but a Lucretiawhen you’ve possessed her.What kind of mind is odderthan his who mistsa mirror and then complainsthat it’s not clear.Their favour and disdainyou hold in equal state,if they mistreat, you complain,you mock if they treat you well.No woman wins esteem of you:the most modest is ungratefulif she refuses to admit you; yet if she does, she’s loose.You always are so foolish your censure is unfair;one you blame for crueltythe other for being easy.What must be her temperwho offends when she’sungrateful and wearieswhen compliant?But with the anger and the griefthat your pleasure tellsgood luck to her who doesn’t love youand you go on and complain.Your lover’s moans give wingsto women’s liberty:and having made them bad,you want to find them good.Who has embracedthe greater blame in passion?She who, solicited, falls,or he who, fallen, pleads?Who is more to blame,though either should do wrong?She who sins for payor he who pays to sin?Why be outraged at the guiltthat is of your own doing?Have them as you make themor make them what you will.Leave off your wooing and then, with greater cause,you can blame the passionof her who comes to court?Patent is your arrogance that fights with many weaponssince in promise and insistenceyou join world, flesh and devil.— Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, “You Foolish Men”My new book, A Beautiful Year, is coming soon!Preorders help authors, book sellers, and publishers — please consider ordering now. Click here for more information and buying options. Thank you for subscribing. Leave a comment or share this episode.

Create Your Podcast In Minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast