- Podcast Features

-

Monetization

-

Ads Marketplace

Join Ads Marketplace to earn through podcast sponsorships.

-

PodAds

Manage your ads with dynamic ad insertion capability.

-

Apple Podcasts Subscriptions Integration

Monetize with Apple Podcasts Subscriptions via Podbean.

-

Live Streaming

Earn rewards and recurring income from Fan Club membership.

-

Ads Marketplace

- Podbean App

-

Help and Support

-

Help Center

Get the answers and support you need.

-

Podbean Academy

Resources and guides to launch, grow, and monetize podcast.

-

Podbean Blog

Stay updated with the latest podcasting tips and trends.

-

What’s New

Check out our newest and recently released features!

-

Podcasting Smarter

Podcast interviews, best practices, and helpful tips.

-

Help Center

-

Popular Topics

-

How to Start a Podcast

The step-by-step guide to start your own podcast.

-

How to Start a Live Podcast

Create the best live podcast and engage your audience.

-

How to Monetize a Podcast

Tips on making the decision to monetize your podcast.

-

How to Promote Your Podcast

The best ways to get more eyes and ears on your podcast.

-

Podcast Advertising 101

Everything you need to know about podcast advertising.

-

Mobile Podcast Recording Guide

The ultimate guide to recording a podcast on your phone.

-

How to Use Group Recording

Steps to set up and use group recording in the Podbean app.

-

How to Start a Podcast

-

Podcasting

- Podcast Features

-

Monetization

-

Ads Marketplace

Join Ads Marketplace to earn through podcast sponsorships.

-

PodAds

Manage your ads with dynamic ad insertion capability.

-

Apple Podcasts Subscriptions Integration

Monetize with Apple Podcasts Subscriptions via Podbean.

-

Live Streaming

Earn rewards and recurring income from Fan Club membership.

-

Ads Marketplace

- Podbean App

- Advertisers

- Enterprise

- Pricing

-

Resources

-

Help and Support

-

Help Center

Get the answers and support you need.

-

Podbean Academy

Resources and guides to launch, grow, and monetize podcast.

-

Podbean Blog

Stay updated with the latest podcasting tips and trends.

-

What’s New

Check out our newest and recently released features!

-

Podcasting Smarter

Podcast interviews, best practices, and helpful tips.

-

Help Center

-

Popular Topics

-

How to Start a Podcast

The step-by-step guide to start your own podcast.

-

How to Start a Live Podcast

Create the best live podcast and engage your audience.

-

How to Monetize a Podcast

Tips on making the decision to monetize your podcast.

-

How to Promote Your Podcast

The best ways to get more eyes and ears on your podcast.

-

Podcast Advertising 101

Everything you need to know about podcast advertising.

-

Mobile Podcast Recording Guide

The ultimate guide to recording a podcast on your phone.

-

How to Use Group Recording

Steps to set up and use group recording in the Podbean app.

-

How to Start a Podcast

-

Help and Support

- Discover

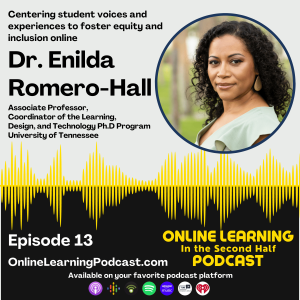

Online Learning in the Second Half

Education

EP 13 - With Dr. Enilda Romero-Hall - Why we love and hate discussion boards, feminist pedagogy online, humanizing large classes, and more!

In this episode, John and Jason talk with Dr. Enilda Romero-Hall about applying feminist pedagogies to online classes, humanizing large online classes, ungrading, and why we love and hate discussion boards.

Join Our LinkedIn Group - Online Learning Podcast

Connect with Dr. Romero-Hall:- Website: https://www.enildaromero.net/

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/eromerohall/

- Twitter: https://twitter.com/eromerohall

- Susan Blum on Ungrading

- Flip - Free Video Discussion from Microsoft

Dr. Enilda Romero-Hall, is an award-winning scholar, Associate Professor, and Coordinator of the Learning, Design, and Technology Ph.D. program at The University of Tennessee Knoxville. Dr. Remero-Hall also serves as the Program Chair for the AERA SIG Instructional Technology and Advising Editor to the Feminist Pedagogy for Online Teaching digital guide. In my research, I am interested in the design and development of interactive multimedia, faculty and learners’ digital literacy, and networked learning in online social communities. Other research areas include innovative research methodologies; culture, technology, and education; and feminist pedagogies.

Transcript

(Please note - we rely on computer-generated transcriptions. If quoting, please check the original recording for accuracy)

[00:00:00] Enilda Romera-Hall: I'm curious to know what the listeners are going to say, what the comments are going to be. Did we say anything too controversial? I think that we need to have more conversations about online learning because there is a lot happening in this space. And yeah, it just keeps changing and evolving and the more conversations we have, the more we can brainstorm and think of ideas to put on the world.

Intro

[00:00:26] John Nash: I'm John Nash here with Jason Johnston.

[00:00:28] Jason Johnston: Hey, John. Hey everyone. And this is Online Learning in the second half, the Online Learning podcast.

[00:00:34] John Nash: Yeah. We're doing this podcast to let you in on a conversation that we've been having for the last two years about online education. Look, online learning has had its chance to be great, and a lot of it is, but a lot of it isn't.

So how are we gonna get to the next stage?

[00:00:50] Jason Johnston: That is a great question. How about we do a podcast and talk about it?

[00:00:55] John Nash: Yes, that's perfect. What do you want to talk about today?

[00:00:58] Jason Johnston: Today, it's not just what, but it's what with whom. Nice. Today really excited to have Dr. Enilda Romero Hall with us to talk with us.

Welcome Enilda.

[00:01:10] Enilda Romera-Hall: Hi. Thank you for having me here today. I appreciate it.

[00:01:14] Jason Johnston: Yeah. Dr. Romero Hall is a colleague here at the University of Tennessee. She's an associate professor in learning design and technology program. And she also I think one of the things that connected us, obviously the whole instructional design thing.

So right away when Enilda came, we also started around the same time. So it was easy to, easy to make friends when you don't, when you don't know anybody. But also the kind of research that Enilda does is significant and aspects of the things that we've been talking about John, but also from some different perspectives as well that we don't have.

And so I just really appreciate Enilda, you taking the time to talk with us

[00:01:58] Enilda Romera-Hall: today. Yeah, it's great to be here. I love talking about online learning. It's one of my areas of interest. And I was actually talking to a colleague who was visiting University of Tennessee Knoxville recently, and he was asking me, how's it going?

Have you met people here? Have you met any collaborators? And I was telling him that I was coming into my first year and I was really wanting to keep a low profile. And I said, then I started telling people that I was doing research on online learning and that was just impossible. Yes. But it's been great.

I've connected with the online learning group and different departments within the university, I think there is quite a bit of interest on online education and hybrid education, and I think that is something that attracted me to university of Tennessee Knoxville on the first place.

Yeah, so it's be, it's been

[00:02:57] Jason Johnston: great. Yeah.

And for our listeners that don't follow Dr. Romera Hall on social media low profile this year means only only five presentations internationally as well as, only I don't know, another five publications. And so yeah. Really. Anyways, yeah, that's good.

Why don't you tell us just a little bit about yourself and maybe your background and how you got to this place first. And then we'll get into some of your areas of interest in, research and how they apply to online learning.

[00:03:27] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah. Yeah, so I started to become interested in e-learning when I was in my master's program.

My master's program was also fully online. But I just happened to be at the location where my school or my institution was located, which was Emporia, Kansas which is a very small town in Kansas. And and that experience of being an online student but also being physically in the location of my institution was just very eye opening.

Because I had a connection to the institution, but I did not know any of my classmates. So there was a lot of interest in getting to know my classmates and making online learning more community oriented. And then I went on to do my doctoral degree at Old Dominion University. And the classroom environment that we had was a high flex learning environment.

So I was there with maybe 10 to 15 classmates, but many of my other classmates were literally all over the world. Italy, Egypt, Morocco, Alaska, so everywhere else. So again, I had another educational experience that was in an online learning format. And when you have those experiences and you are also studying instructional design and technology it just really makes you curious on ways where you can shape online learning and how to improve it.

So it was just a combination of my experiences as a learner and then guiding my research interest and then going into a faculty position and looking at my research agenda, it just it was just like a perfect match. So it's just, again, the connection of already having that experience as a learner, being a faculty member and teaching in those formats, and then doing research.

And in the process of doing that, I've also learned so much from so many different people. Learning about how to teach in an online learning format using a learning management system because that's what's required by your institution. What are birth practices for a learner center approach but also keeping in mind how to humanize the online learning experience.

I'm thinking through different frameworks. For example, I have connected and implemented so much of feminist pedagogy in online learning experiences. To again, keep in mind the learner and how to we make this experiences more social, more connected, more human, so I would say that has been like my journey into this research endeavor.

Yeah.

[00:06:40] John Nash: That's wonderful. as you think about humanizing online education going forward, what sort of aspirations do you have for the future of e-learning?

[00:06:52] Enilda Romera-Hall: Oh my God, there's so much. In a very basic sense I feel that the initial work has to be done with faculty. I think professional development is key to the very basic essence of humanizing online learning because we are still having conversations about the value of online learning.

And I think that comes with professional development and educating faculty members and teaching them this is what you can do. It, It is not easy. Um, I think that online learning presents lots of I, I don't wanna say challenges, but yeah, teaching challenges because in order to do it effectively, you have to invest and do the work.

But I think at the very basic core is yeah, investing in professional development and making sure that faculty are on board and know how to humanize online

learning.

[00:08:07] John Nash: When you think about faculty knowing how to humanize online learning, then it gets a little operational, doesn't it? But could you say a little bit about the way feminist pedagogical tenets might support that learning journey for faculty?

[00:08:21] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah, sure. There are no absolute set of tenets that one can follow. But I think at the very core feminist pedagogy focuses on giving the learner agency. I think that that is something that when we think of traditional learning experiences they tend to be very instructor focused.

So feminist pedagogy is about giving the learner agency including learners as part of co-creators of the learning experience. And that could be a multitude of different things. It could be from the very first day looking at the syllabus together, or it could be let's challenge the traditional format of already figuring out what we're gonna teach this semester and let's think about that experience together.

It could also mean thinking of looking at the type of assessments that we're gonna have for the class and including the learner as part of that experience. And it also considers power and authority, so it tries to avoid. This sort of like hierarchical format in which I am the instructor, you are our students, and this is the dynamic that we're gonna have in the classroom.

Rather it looks at bringing the student and their experiences and the value that those experiences bring to the conversation, the exchanges, the discourse that happens in the classroom. It also has a social justice element in which learning is not just kept within the virtual classroom or the physical classroom, but is giving back to society.

Best examples that I can think of is, creating open educational resources that can then be shared with another community of learners or other individuals. So there's, again, there's a different kind of dynamic that occurs when you're integrating feminist pedagogy.

Mm-hmm.

Um, And one thing I always say is that's a framework that I can identify with and works for my learning experiences, but of course, there are other frameworks that can be also integrated or may work best for other instructors.

[00:10:54] John Nash: I appreciated how you are able to think of very simple entry points for faculty to adopt a feminist pedagogy by just thinking about just sharing resources and having dialogue is just part of the, is an entry way to even bigger things that they wanted. I appreciated that. I have more questions about that, but I wanted to see if Jason had something that, what struck him during that.

[00:11:17] Jason Johnston: I was curious about the ideas of agency and power and social justice I think are somewhat common to a lot of critical pedagogies as we're thinking about trying to reframe and trying to improve the way that we're doing educational work, whether it's face-to-face or online.

I was curious more about what is maybe specific to feminist pedagogy that we may not find in some of the other critical pedagogies.

[00:11:46] Enilda Romera-Hall: I think that one of the central ideas is the idea of equity. I've used the term feminist in different contexts and different institutions and often we think of just being centered about on, on women's rights, but there's an element of it that is um, related to equity for all. And I think that is a little bit different than other frameworks that are more centered on collaboration or bringing the use of online tools and, how do we use, use online tools so it centers on equity and making sure that learning is accessible to all.

So I think that it has an element of universal design to it. But it also has element of collaboration and accessibility. So to me it just brings all of those different concepts and frameworks together into one kinda umbrella. And that, that's why I like to consider it like my go-to framework when I am thinking of online learning.

The other part that I think it, why it resonates with me so much is because often we think of online learning with just putting content in an online platform, and it is very much content driven. So what are we going to teach? What's the assessment going to be like? And considering the learner is like a, an afterthought like, okay, everything's already designed and developed, and now we have the students come and take the course.

Whereas in feminist pedagogy there's still that flexibility. Despite an instructor thinking through what they're considering going they're going to teach, or what they're considering they're going to do for assessment, the learner is still gonna be part of the equation. And there's flexibility on how the approach is going to be integrated, into a course.

[00:14:02] Jason Johnston: That's really helpful. Yeah. And yeah, I've often had concerns about how, even in my own work, how often design happens in a vacuum. And it may just be the faculty member, it may be a faculty member, an instructional designer. But again, pointing back to what you said previously about how important that professional development is, that awareness is so that if the student is not part of that, especially initial design process, that at least there's some awareness to issues of equity within the design that they're creating at that point before they roll it out in front of the students.

[00:14:42] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah. I've actually, I have been teaching in higher education for the last 10 years, and I have yet to have a learning experience set from the very beginning and be set that way until the very end. Because I wanna know what my students are interested in and what are topics that we need to modify as we go along the way.

Or I might create an assessment and then realize that the students may need more time or they may need less time for it. So again, I think feminist pedagogy in my practice allows for equity because it gives me flexibility to change and modify as I see needed with the students that I may have that particular semester.

[00:15:36] John Nash: Is it also that it gives you multiple lenses through which to see learners and their experiences? You, I think you mentioned in some of your own reflections about that there's an intersectionality to this that is helpful as a professor and a researcher and a teacher.

[00:15:54] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah, absolutely. The students are very diverse and diversity comes in different forms, right?

In cultural background, Racial ethnic groups, learning experiences that they may have had, professional experiences that they have. And it's really important to identify who the learners are. And that shapes, moving the teaching experience moving forward. And I have reflected on this piece about intersectionality so much because the instructional designer in me thinks about the design and development of experiences without having any idea on who's gonna be the end user, the end learner, right?

Thinking through that piece is extremely challenging. And then again, I have my two hats of like instructional designer practice, and then my instructor practice. And as an instructor I get to modify and be flexible. But from the instructional design perspective, that's again, very challenging because the instructional designer may not get as much information or doesn't get the opportunity to have that flexibility.

So yes, intersectionality is very critical to the work that I do as an instructor, as a, at least that's how I see it. And is a lens through which I see my practice on a weekly basis.

Nice. Thank you.

[00:17:32] Jason Johnston: Talk to us a little bit about, okay. I'm gonna throw a challenge out to you now that we're getting into the things here.

Don't mean to put anybody on the spot, but here's one of our challenges. On the front end, as we are designing courses, we often ask about a class size. It's a pretty classic kind of question when it comes to designing an online course. How many people at one time is gonna be in a section here? Because that changes your dynamic quite a bit.

Yes.

Talk to us about scaling courses, I think being reflexive or being thoughtful and responsive to your students is all well and good when you've got 15 of them and you're able to get to know them all personally.

But we've got courses that are like a hundred to 200 people inside of this course. Are there obviously the approaches are still good to keep in mind. Are there ways that it changes your thought about application, if you were in that situation?

[00:18:30] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah. That's a great question. Because I have heard from faculty who are teaching very large online classes and I think that there's an element of collaboration that needs to happen in this really large process to make the learning experience more fruitful for the student as well as a good experience for the instructor.

But a disclaimer before I move forward: I don't know how how much support I have for massive online courses.

Sure.

I, so I think that, I feel I have certain feelings and emotions towards really large online classes. Because

you can say those feelings here.

Yeah. Because I feel that, you're not gonna get the same learning experience with a large number of students. You're talking eight, 100 plus students. That's, yeah. But I think that there are elements of collaboration that can happen that can allow students to connect with their classmates.

And allow the instructor to connect with the students. And I think in the best scenario that makes for teamwork, again, collaboration that can allow for reflection. And that can pro allow the instructor to feel connected to their to their students. But I don't know if I can give you a full answer when I personally feel that, there's a certain number of students that should be in a class, and there's a certain number of students that should not be in a class, right?

[00:20:26] Jason Johnston: Yeah, I think we have to be honest about our own feelings about it, but also just realistically if somebody gave you the challenge of, map the most effective route to drive to London, England. I would like to, but I can't I don't know how we get there from here.

If I just hop in my car today, now, there may be a way to do it, but I'm not sure exactly I can get it part of the way there, but maybe not all the way there.

[00:20:50] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yes. One thing about, really large online classes, Isn't it really like a MOOC, but a requirement for a grade? And I think that type of course design should be based on the MOOC literature and we know the completion rate of MOOCs.

So, why would we have that kind of expectation for a really large class that is offered as a regular semester course for an undergraduate student or perhaps a master level student? I don't know. I find it really challenging, to be quite honest. Yeah. And I have a student who is running a really large class like that, I, I don't even wanna say the number, but I find it very challenging.

[00:21:45] John Nash: Is part of that challenge, does it manifest itself because there's a disconnect amongst university leadership on what is the capacity of an instructor and what is the right number for any class? I love your idea of the fact that they should probably be considered MOOCs. Enilda, we met a colleague at another institution at the O L C Innovate conference in Nashville who confided in us that her institution's section caps, not course caps, section caps are 999 students.

Oh, wow.

Now that's not, that's never practically met, but they never hit that. But the fact that number gets written down as policy somewhere as a section cap just tells me there's a disconnect amongst leadership that what pedagogy really means in the institution and how knowledge should be constructed and how we should make students agentic and sort of the feminist pedagogical tenets, how can you bring those into a MOOC? Is there a disconnect amongst leadership and amongst instructional designers and teachers on what's going on?

[00:22:54] Enilda Romera-Hall: I think definitely there is. If I think about an online course, and the challenges that are already presented in terms of interaction between the student and the instructor, the student and the content, the students and the other classmates.

And then I multiply that by whatever number of students are in the class. That just seems like a recipe for, I don't wanna say disaster, but a recipe for a very challenging semester. And I don't know what the outcome of that learning experience is going to be for the student. And I know that I've seen a lot of discussion in terms of what is a good class size.

I don't know if I have seen a final publication or research on this, but I would personally be very interested in that number because there are limitations with how much you can reach a student when you are talking about 900 students.

I have 15 to 20 students in my class and I feel that I have to check in on them. They have live experiences that happen and that makes, the learning experience different for each of them. And there's a connection that has to happen between the structure and the student in order to really understand what's happening with them and how you can fully support them because you're not just providing content, you're supporting it learning student through their learning experience.

So I do think that there's a disconnect between the administration, instructional designers what the students want, and then what pedagogy really is. When you are thinking that it's okay to have 900 students, it really, for me is really a MOOC. But the difference between running a course at is taught in a regular semester as part of a student's requirement for graduation and a MOOC. It's completely different. The two are two completely different things to me.

[00:25:14] Jason Johnston: Yeah. And I think those are good distinctions in, if I can play kind of the other side a little bit, cuz I've had conversations with various administrators,

and so I think that I can see the side of, for instance, a lot of programs are kinda like funnels and they start really large and there's some, a lot of foundational information that needs to be gathered for the student. And if we think about the Blooms technology, it's all that base level of that pyramid to be able to build knowledge and, a lot of that can be done through automatic quizzes and assignments and TAs and all the kind of things that would happen in a really large course. And, but then other courses as the funnel gets smaller and smaller. Should have smaller class sizes so that students can have a little more personal attention from their teachers so they can have some mentorship so they can have some back and forth and those kind of things.

And I see that perspective. I think that if a student front to end all their classes are large and impersonal, I, I don't think that we are serving the student very well. However if it's a mix of courses, I think we could serve a student pretty well if students have a mix of courses, because I don't, I, I don't know what you think, but I don't think every, class has to be life changing, although I know it's our desire, as a teacher, But I think in some ways students can only handle so many life changing courses at one time.

And I also think that depending on what your objectives are for that course, it may be okay for a course not to be life changing and it just provide a foundational experience of information. Does that make sense?

[00:27:00] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yes, absolutely. I think the challenge is when those large courses are facilitated through a digital format, an online format and the kind of support that the students are gonna get and the kind of support that the instructor are gonna get, I think that when all those things are in alignment and they're well supported, I think.

I agree. I don't think every course needs to be life changing. There needs to be support for, again, the students and the instructor for it to be facilitated correctly. But I do think that for an instructor who is teaching online and is teaching online for the very first time or the very first few years in a really large class like that it can be very challenging.

Yes,

Yeah, yeah I think it can be very challenging and I hope that they would have the support. I hope that the institution is able to provide the support that they need in order to, for them to be successful for this the students to be successful too.

[00:28:08] John Nash: I worry about, I wonder if our listeners will think we're conflating life changing with like boring or, I, there, I, how do I want to say this?

That I think. That the courses, we don't want them to end up being a stove pipe where it's just forgotten after the course ends because there ought to be some articulation across the curriculum that this is a foundational piece that builds on the next thing you do. So while you were in a large class, it hopefully was more of an experience than just a large lecture, but rather there was some chance that you take what you learned and you'll move it to the next piece.

Even in, I see it in doctoral programs, courses at the beginning still are a bit stove piped and in their own world, they don't get, they don't get articulated to the next piece. And I don't know if that makes sense or not, but I think that's part of the thing is that maybe it's not changing their life, but at least they remember what they learned.

So it, it applies to the next piece in the program.

[00:29:07] Jason Johnston: John, I don't mean to pick on you, but we're around the same age, and so I'm just gonna pick on you for a second.

Could you explain to our Our younger listeners what a stove pipe is. I think a lot of them might be scratching their head, like thinking about where the pipe goes on the stove.

[00:29:21] John Nash: Oh yeah. Or well, siloed, I should have said siloed. Yeah, siloed. Yes. But this, that imagining that all the content is inside a silo or a stove pipe and it goes straight up and doesn't get to touch the other sides or stove pipes.

And we think about these, they're called verticals, I think, in fancy business talk.

[00:29:40] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah, and I think that most educational experiences at the undergraduate level, half courses like that. I'm trying to think, but one course in earth science that I thought that was a general education course, right? It was probably the one earth science course that I took because I was a business major, but, it still was valuable to my undergraduate degree.

So I think that yeah, I think there's value to every course that you take. There are some courses that are going to be more impactful in your future careers and others that are just gonna be just general knowledge.

[00:30:19] John Nash: It would be wonderful if the specialized courses later in a student's undergraduate career, those professors knew of the general ed requirements they took, and they could even talk about and refer to that experience with the students.

So you remember when you were in your Earth sciences class, you covered these things. Now that we're in this business major though, these things are actually connected now. That would be wonderful.

[00:30:42] Jason Johnston: That would be ideal, yeah. Yeah, and I completely agree and I think it takes a lot of coordination. I do think that faculty too often are creating courses in their silos. They're handed a topic or a a syllabus and they're expected to move forward with it without necessarily thinking about those interactions among the other courses and where they are in the curriculum and how it's progressing.

[00:31:06] Enilda Romera-Hall: But I do wanna say I was actually talking to a faculty member in the College of Business and she was telling me about a course that she's teaching in the fall and how there are two courses that are very much connected. So she's actually gonna work on her course early on in the summer.

So the second the faculty member for the other course can avoid any repetition of content or can move to more advanced content in her course. So I think that in some settings those type of interactions and collaborations are happening. And actually in our learning design and technology and then the instructional technology program, we do have conversations about content that happen between myself and other instructors to, again, avoid repetition.

So I think that those conversations, again, are happening. We may not be as vocal about it but it, I think it's a good thing. I definitely feel that when you are in a program of study, you would expect faculty to connect and have conversations about the topics that are being covered.

[00:32:25] Jason Johnston: Yeah. That would be wonderful. Yeah. Yeah. I think the communication relationship is ideal. I think sometimes you can use some data and even student data, they often will tell you, I remember developing an online program and a number of the instructional designers we were working with were really getting into infographics, like having the students create their own infographics and so on, which I think is a really great idea for presenting material and presenting a synthesis of what it is you're learning without making them write another five page essay.

And so really unique, great idea, except that it just so lined up that the courses that were being designed, like every course the students were taking in that sequence that semester, they were making them create infographics. And the students were like, no more infographics. It's not that we don't like it, but it's like we're having to do an infographic now for every single course, like in the fourth week or something.

And that was just feedback from the students. It wasn't from any kind of overarching or communicative kind of thing between the designers or the subject matter experts. It was just students rising up and giving voice to that. And we're okay, we've heard you, we've heard you, and we'll either space these things out or we'll switch a couple of these assignments up and so

on.

[00:33:37] Enilda Romera-Hall: I think student feedback is key. It helps us in so many different ways. And just to take that and go back to the conversation about large online courses, I think that if institutions are doing these large online courses and the feedback from the students is positive, then by all means

Yeah.

Because that's what should drive, decision and course design and improvement and things like that. So I, yeah, I. Yeah I think the idea of student feedback is extremely

[00:34:17] Jason Johnston: beneficial,

Right,

you asked a question about what the ideal course size, and I think the answer is, it depends, right?

Because, and it depends on how you approach it. I could imagine a small course with a very inflexible instructor could be less humanized than a large course that perhaps uses a lot of data and is able to respond to students needs in a different kind of way that is very flexible, perhaps, or, and even technologies or tools or approaches that are flexible could almost be more humanized in a hundred person course than in a 10 person inflexible course.

Does that make sense?

[00:34:59] Enilda Romera-Hall: That absolutely makes sense to me. And I think that there, the use of. Collaborative online tools can can be implemented in different ways that can allow for more exchanges, for more communication and again, beneficial to both the student and the instructor. I actually, I'm thinking like this is a great dissertation topic for somebody because again, I haven't seen it in the literature.

And I'm actually going to check. Check the literature after our meeting to see if there's anything out there, but just this idea of core sizes and is specifically in online learning settings. So

[00:35:43] Jason Johnston: yeah

just another great reason why people should be listening to this podcast. Not only humorous and helpful banter and conversation, but online learning, but it is ripe with dissertation topics and for for the research and ways that people can learn.

I would. I would agree. Yeah.

[00:36:00] John Nash: And NoDa, I learned that you and I share an abiding interest in UN grading and I, I implement un grading practices in one of my doctoral courses. It's an online course. You talk about it too, and I was looking at it, a crosswalk from un grading to the feminist pedagogical tenants to, and then I teach a design thinking course and I've affiliated with the design justice network.

And they also think similarly about emphasizing learning over sorting and judging and centering the voices of those impacted by the process at the heart of your work. Would you mind talking to us and everyone listening about the benefits of un grading as a consideration and taking forward the humanizing of online learning?

[00:36:52] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yes, absolutely. So I'm a huge proponent of going through the learning experience with the idea that you are there for knowledge and skill. I feel that it makes the learning experience more valuable to the learner rather than making sure you are checking every box as you're going through the semester, because then you're just going through the experience to do the work.

But are you improving as you're going through the experience? And this was particularly important to me because in my previous position, I was teaching to master level students who were preparing to be instructional designers in practice. So they were going to graduate and they were transitioning for whatever career they were in to be instructional designers.

So, the quality of the work that they did was very important to me because I wanted to make sure that they would graduate with knowledge and skills of an instructional designer and be able to get a job and be able to support their families or move forward with their career. I wanted them to be successful.

I focus on mastering skills through the design process. Much of my work as an instructor was really incorporating project-based learning in my courses. So they would have normally a semester long project. And in order for me to see a student growth, I needed to be able to have an assignment, give feedback to the student, allow them to implement the feedback, grow from that experience, and, continue that process through the semester until the very end.

So ungrading really allow me to, to embed that process into my courses and not have them focus on, "I did the needs assessment. I checked my box, I moved to the task analysis. I checked my box, I moved to, the, I don't know, storyboarding and I check my box." I wanted them to grow.

So it's so similar to, I'm thinking, going through a design thinking course where you need them, the student, to evolve and grow. And that was the approach that worked for me in that setting. And also another course that I taught is the course where the students had to work on their professional portfolio, which for me, a professional portfolio is an never ending process because you're always adding to your professional portfolio,

you're always editing. So I moved primarily from grading and assigning points to this really is a course where you pass or fail and really you're growing through the process, so I see you as passing as you're going through the process. So those were the main reasons why I integrated an on grading approach into my courses because the way I see it from the day the student walks into the course, the very first day of class, until they are ending the semester, they have already grown through that experience.

And having an upgrading approach really allows the student to focus on the task at hand rather than focus on, did I get this points, did I not get this

[00:40:35] John Nash: point? Yeah. And I've been subscribing to the tenants, but. Of Susan Bloom, who's at Notre Dame, and thinking about a reflective component at the end where the student then institutions still insist upon a mark or a grade being put into the grade book at the end, don't they?

And so something has to come up so students are having a dialogue with me or, and perhaps you and others about their growth and then maybe even suggesting what grade they think they they deserve based upon their own reflective processes on quality of their own work, how they've grown. Is that sort of how you're looking at it as well?

[00:41:15] Enilda Romera-Hall: We always have a reflection at the very end of the semester. One of the things that I have implemented through this process is we share all of our work. So whatever work the students do, I share it with with the class. They see each other's work. They critique each other's work.

I sometimes it's challenging because I think that students are not used to critiquing or giving feedback. That's right. So I have to integrate mechanisms into the course that allow for critiquing and giving feedback. Like I had the students this semester do a presentation. In addition to that, they had to create an online learning module and they were given their presentation by using the online learning module that they had created.

And then I had a Google document in which each student was required to ask a question one to two questions. And then they were required. They had a, we had another Google document in which they were asked to share a key takeaway from the presentation. And that allowed them to question, so question, give each other's feedback.

And then the key takeaway was like, what did you take out of this learning experience that you would like to share with the class? So yeah, having those reflections is ongoing. But then at the end of the semester, we always have another kind of like pow wow where we get together and talk about the final product that they have created.

And they find that to be very powerful because I may have seen the product throughout the semester, but they get to share and take ideas from each other and reflect on their experience and their growth. Yeah.

[00:43:10] John Nash: Yeah, really nice.

[00:43:12] Jason Johnston: Do you think that helps with student motivation when they're sharing with one another versus just directly sharing with the instructor?

I know a lot of, one of the criticisms of ungrading is how do I motivate my students? Which is a little bit of a lame question in some ways. If the grades are the only thing that you're using, if it's the only thing you're using to motivate your students, I think we need to be,rethinking how we're doing classes anyways, side tangent.

My question is, do you think I, is that helpful for student motivation?

[00:43:44] Enilda Romera-Hall: I think it is. I think that it makes them bring their A-game. Because everyone is going to see what you have created. At least in my classes, the students are creating things are doing projects. And I think that it makes them bring their a game like everyone is going to see that infographic that you created everyone's gonna read that blog post that you wrote about the guest speaker and I feel like I push my students even a little bit more because sometimes I would say we had a guest speaker.

You're gonna write a blog post about the guest speaker, and by the way, I'm gonna share the blog post with the guest speaker, which I have done. Yeah. So I do think that it makes them put their best foot forward. One other thing I was gonna say. And I don't know how that's gonna sit with those who listen or with you two.

But I am not a huge fan of discussion boards. But I remember one semester I did implement discussion boards and I said to the students this is for you and you're gonna participate on your own. I'm not gonna do the write a post and comment to two people. And the students actually participated a lot more than, in the past when I've had seen that, here's one post and comment to two things.

Because they just felt like it was a natural conversation. I think they felt less pressure, it just felt, again, more natural. So I think that the idea of assigning points to everything make students be more, make them more robotic in some instances and checking boxes through procedures.

So I think that sometimes it's okay to give the student the ability to do things because they want to, not because it's a requirement.

[00:45:52] John Nash: Yeah. I think it helps them think about themselves as becoming more of a knowledge colleague with you and me as instructor. Then as a sort of a power teacher learner culture, I think that they get to talk with you about their ideas and you give feedback and it culminates in a better product.

[00:46:14] Jason Johnston: And their colleagues, they're working on, they're working on knowledge creation together with their fellow students versus just with the teacher as well.

[00:46:23] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah. And I think that sometime having those conversations with the students is really important or create awareness to the students because I tell my students to me, you are instructional designers, because that's what they're working on, to me, you are, you're my future colleague, and the first day of class I tell them, look to your right. Look to your left. That might be the person who may hire you when you graduate. Treat each other. Treat each other like colleagues. Don't treat each other oh, that person who's in my group.

So sometimes setting the tone in the conversation with a student is very important too.

[00:47:04] Jason Johnston: Just a small note about discussion boards, I'm no lover of discussion boards, especially the, post wants respond twice, what feels like a ongoing trope almost. However, I do challenge people sometimes I get feedback from faculty who say students hate discussion boards.

I don't like 'em either, so I'm just gonna cut 'em out all together. My challenge is, figure out how then you're gonna replace that student to student connection. That's the challenge here. The discussion board is not the goal. The goal is student-student connection over the content and over their ideas and whatever else that they're promoting.

And so it doesn't mean that I'm in love with discussion boards and you have to have them, but it does mean that if you just. Think they don't work and students don't like them and you don't like them, you're just gonna cut it out all together in your class. You're taking a step back then even from some of the worst discussion boards.

You're taking a step back if you're giving no agency for your students to be able to say something to their entire class.

[00:48:09] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah. I actually integrated the, I think it was, it's called Flip. Oh yeah. Yeah. Into one of my classes and and then I thought it was like fun challenges the students could do.

I said... we were covering Learner Motivation that week, and I said I want you to read a journal article and then I want you to summarize it in one minute. That was a lot of fun. They seem to like that. So I think that thinking creatively through the process of how to interact with the student or.

Have the students share is, it can be fun. It can be yeah, we have to think of ways that the learner is going to engage, right? So I felt like it was, they have to read the journal article and then they have to synthesize it in one minute. And they seem to enjoy that.

[00:48:59] Jason Johnston: Do you tell them with or without the use of ChatGPT?

[00:49:03] Enilda Romera-Hall: No, but I didn't include that in my description of the assignment. I'm curious now if they used it or not. It is there for them to use, so

[00:49:15] John Nash: I think that's really neat to put a cap on it. Like I've done that also with. Just in discussion boards when I've used them, I put a cap on the last answer.

So 300 words, it can't, it's not a minimum, write at least three. It's no, please do not go over 300 words. Do not talk more than one. Flip is nice because they cut you off at one minute. But that forces learners also to think about what are the key cogent points I need to put in front of someone to really make my mission.

[00:49:41] Enilda Romera-Hall: Yeah. Yeah. That's what I was thinking too. Like you have to be very concise and you have to be very intentional on what you're going to say. There's an element there of synthesizing the research. So...

[00:49:56] Jason Johnston: definitely. That's great. Thank you so much for spending your time with us to have this amazing conversation.

We need to have you back at some point because I feel like there's so much more that we haven't even covered. And we could talk with you all day long, but we'll just have to we'll just have to leave that for another time if that's okay. And,. Is There Anything else that we didn't say or that you wanted to say your piece about before I said my piece about discussion boards.

I just had to get that out there. You said yours is there, but if there's anything else, is there anything else that you would like to say before we close off?

[00:50:31] Enilda Romera-Hall: I don't think so. I think I've said everything. It's been a fun conversation. I feel that we can talk about many other things as well.

I'm curious to know what the listeners are going to say, what the comments are going to be. Did we say anything too controversial? But no, I really enjoy that. I think that we need to have more conversations about online learning because there is a lot happening in this space. And yeah, it just keeps changing and evolving and the more conversations we have, the more we can brainstorm and think of ideas to put on the world.

Yeah. Thank you for having me.

[00:51:08] Jason Johnston: Oh yeah. Thank you. And you do a very nice job of updating both your LinkedIn as well as your website. Do you wanna direct people to one of those?

[00:51:19] Enilda Romera-Hall: Sure. You can connect with me at www.enildaromero.net. I'm also on Twitter at ERomeroHall and you can find me in LinkedIn Enilda Romero Hall.

[00:51:34] Jason Johnston: That's wonderful. And we'll put those links in our show notes as well. Online learning podcast.com is our website as well as find our online learning podcast LinkedIn Group where you can say whatever you're thinking about this episode and whether or not you agree or disagree, would love to have more connection and communication.

I think, John, and I don't wanna speak for you, but I'm going to right in this podcast

you do all the time. It's cool.

But I believe that part of our ideal for this podcast is not just to do a one way communication out to people. Yeah. To dispel our own ideas. We really would love to create a community around these ideas and hear from people.

We're not coming here with a bunch of answers for everybody, and we probably have more questions and answers. And so as part of that, we would love to hear from people. The space in which we're trying to do that right now is our LinkedIn group. And so if you've got any ideas about this, we'll post a podcast and please chime in and you can always find us at LinkedIn as well.

Send us messages and let us know what you think. This sound accurate, John?

[00:52:39] John Nash: That sounds accurate. We are filled with far more questions than answers and mostly just testing little hypotheses all the time. That's all we do.

[00:52:50] Jason Johnston: Yep. But it's great to have guests like Enilda, thank you so much with us to talk with us.

This has been a great conversation and thank you John as well. Yeah,

[00:53:00] John Nash: Thanks everyone. Take care.

More Episodes

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2025 Podbean.com